As housing prices and rents soar out of control in tightly regulated cities like San Francisco and New York, many people have called for a significant loosening of zoning rules to permit greater densification. Many policies contribute to unaffordable housing, including rent control, historic districts, eminent domain abuse, and building codes, but zoning puts an absolute cap on dwelling units per acre thus is generally part of any solution to the supply problem. What’s more, as recent commentators have started to notice, even many of America’s most dense cities are predominantly zoned for single family homes, calling into question the need to dedicate so much space to a single housing typology.

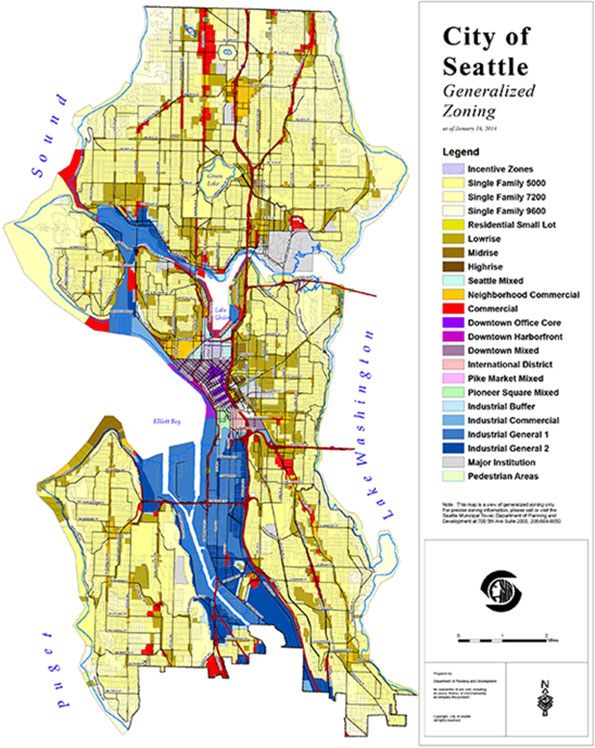

For example, a web site called Better Institutions posted this map of Seattle, in which all of the yellow districts are zoned exclusively for single family homes:

The poster lets his feelings be known by using scare quotes to denote single family “character” and blaming the zoning for Seattle’s high rents.

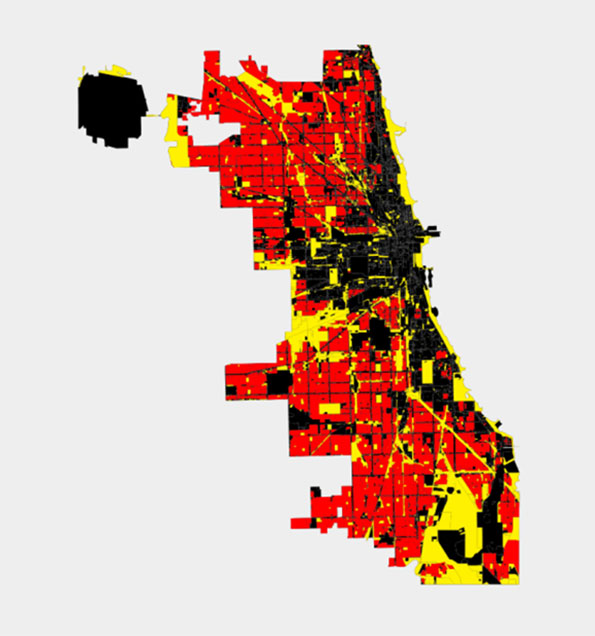

And Daniel Hertz posted a similar map of Chicago in which the red is single family homes only and yellow is industrial space unavailable for any residential use:

Some go beyond affordability, saying that we also need to significantly increase densities in central cities in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Harvard professor Ed Glaeser wrote an article advocating this subtitled, “To save the planet, build more skyscrapers—especially in California.” He says, “A better path would be to ease restrictions in the urban cores of San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, and San Diego. More building there would reduce average commute lengths and improve per-capita emissions” and “Similarly, limiting the height or growth of New York City skyscrapers incurs environmental costs. Building more apartments in Gotham will not only make the city more affordable; it will also reduce global warming.” He claims that, “The best thing that we can do for the planet is build more skyscrapers.”

These complaints and the proposed solution of more dense multi-family development may be true in a technical sense, but what would carrying that out mean for people who actually live in our cities?

Some critics may disdain the character of single family districts but few of these pundits ask the question of what eliminating lower-density housing actually means to the survival of the urban middle class. Districts, like the Portage Park example Daniel Hertz gave in Chicago, are some of the last bastions of middle class family life in the city. It’s clear that some densification can be implemented without radically changing the appearance or functioning of the built environment. Allowing 2-flats and coach houses, or even the corner apartment building or townhouse development, wouldn’t ruin Portage Park. There’s no reason such things should not be allowed. But nor would they make a major dent in affordability in places where a tidal wave of global demand is washing over the city such as in San Francisco.

To materially boost the number of units in an era in a manner that moderates prices in a highly desirable place like San Francisco would require massive changes in the built environment of its neighborhoods. This would radically transform the character and nature of the city in question. If San Francisco were really covered in skyscrapers, it would cease to be San Francisco--- a city of low-rise buildings framed by hills that would be obscured by high rises. There may well be the same geography on the map labeled as such, but it would be a completely different place. We would have to destroy the city in order to save it.

One person who gets that is Alex Steffan. He’s angry about prices, saying that the “criminal lack of housing is a global scandal.” He’s also honest enough to forthrightly acknowledge that a sufficient scale of new homes to bend the cost curve would fundamentally change many of our cities:

We can build some housing incrementally, without changing the skyline or cityscape, but not anything like enough. To produce enough homes to matter, fast enough, we're going to have to fundamentally alter parts of our cities. That, of course, demands a local government willing and able to plan and permit such widespread change. It also takes an array of homebuilders doing the actual work, often in more innovative and low-cost ways, like more collaborative housing, manufactured buildings and flexible living spaces. Most of all, it takes broader public insight into how large-scale development can improve our cities.

In other words, it’s a major change in communities that requires selling the public on the idea. He believes that young people will be the agents of change here. This shows perhaps one of the signature affects such changes would have. They would displace families by eliminating their preferred housing typologies in favor of forms more amenable to predominantly younger singles or the childless for whom living in an apartment with no backyard is more likely a relief than an imposition. But it’s hard to imagine cities as places for solving the problem of climate change if they are, like San Francisco, increasingly places devoid of families with children.

Steffan also says affordable housing is a social justice issue. Yet is it really social justice to require everyone to have equal access to San Francisco, population 825,000? I think not. Especially not when America is replete with urban centers whose biggest problems are depopulation and worthless houses that you can’t give away. There are plenty of options of places for people to live; we should look at making our now failing cities more attractive to people who may like the housing and neighborhood, if not for issues such as crime and poor schools. There’s no guarantee in America that you can afford to live in the place you might most want to choose. That’s long been true of suburbanites and city dwellers alike.

Also, the willingness to fundamentally reshape cities is odd in light of the fact that such previous attempts are uniformly viewed in the urbanist community as disasters. The idea of Manhattanizing San Francisco brings to mind nothing so much as Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris, in which the historical cityscape is replaced with towers in the park.

Of course no one is actually saying to take it this far, although Glaeser’s vision gets close it. But once we enshrine the rule that a certain threshold of unaffordability means more density and building regardless of neighborhood character, it’s hard to see what the limiting principle would be. Also, high rises or even buildings above 4-5 stories in height usually require expensive construction techniques, and thus are inherently costly.

It’s true, however, that cities are not static entities. Every downtown skyscraper in America is built on a site that was once used for something else. Yet we see this densification overall as a good thing. Had Manhattan been preserved as of its pre-skyscraper era, it’s not clear the city would have benefitted.

Clearly the zoning and building regulations in our cities are often too strict. Yet the disasters of previous generations’ radical change suggests that incrementalism is a better course. By all means allow two-unit houses, corner stores with upper story apartments, etc. into currently all-single family zones. Add areas where high rises are allowed the peripheries of districts currently zoned for such; warehouse districts as well as office buildings that are not well occupied. But don’t bring out the bulldozer wholesale. Additionally, a healthy city should make sure to embrace the entire palette of housing types – including single family homes. There’s more to making cities attractive to middle class families than just cost, and things like the prospect of a backyard for the kids to play in are among them.

And given the relatively few intact and attractive urban cores in America, prices are going to continue to go up. That’s true even with radical new building. As mentioned, San Francisco only has a bit over 800,000 people. Boston and DC have only about 600,000 each. How many people can you plausibly put into these places? Realistically, not all of us who would like to live in San Francisco or lower Manhattan are going to be able to do so. That’s true no matter how many skyscrapers we build.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile.

Lead Photo: More density in Los Angeles

Density, upzoning and land rents

The UK's urban economists, with their much longer experience at analysing the effects of growth containment policies, largely disagree with Glaeser et al that non-boundary "anti growth" regulations have much effect at all on housing affordability.

By way of illustration, house prices in low density Boston are about the same in real terms as house prices in the UK's very high density cities. The fact that Boston has minimum lot sizes as large as a whole acre in new developments, yet in the UK typical new developments are 20 units to the acre, does not result in the tiny-lot homes in the UK being any cheaper.......!

Glaeser, Ward and Schuetz (2006) find re Boston, that every added 1/4 acre mandated increases real house prices 4%. Considering that all fringe-constrained cities in the world have house price median multiples of around 6 and those without constrained fringes have median multiples of around 3, this suggests that the fringe constraint is responsible for a 100% increase in "house prices". This is regardless of density mandates or otherwise. Of course the raw land price inflation has to be 20+ times, to explain this. And it is.

Specifically where Glaeser et al and the UK economists disagree, is that Glaeser thinks that allowing higher density development would improve affordability. Experience in the UK utterly disproves this. Constraining the fringe means that added "economic rent" per housing unit will be to the order of around 3 times annual household income. Three times annual household income, would typically buy ten to twenty acres of rural land. If the embodied raw land cost in fringe housing is 3 times annual household income with a 1-acre lot (in, say, Boston) then the inflation is 10 to twenty times. If the embodied raw land cost in fringe housing is 3 times annual household income with a 1/20 of an acre "lot" - as in the UK - then the inflation is 200 to 400 times. And indeed it is this high on the fringes of UK cities.

I suggest - and I know Cheshire and other UK academics agree with this - that "upzoning" merely increases the capital gain to site owners; it does not result in greater per-unit affordability at all. This is also obvious in fringe developments in Canada and Australia where quite high densities are the norm; and also in newly-permitted high density developments.

It is also worth noting that in Singapore where the land market is virtually suspended altogether, "housing" median multiples are still around 6 to 8 even when there is no site rent gain to cope with. This is impressive compared to Hong Kong, which has median multiples of 14+, for smaller units; but affordable cities (median multiple 3) all have average housing sizes several times as great. Singapore's data suggests that the cost of "building up" alone, results in median multiples of 6 rather than 3; while increased site rents (absent in Singapore) are responsible for several more points of median multiple increase in the absence of rent-minimising fringe development freedom.

I also suggest that Manhattan's most impressive "building up" mostly occurred during the era of freedom of fringe growth of the NY urban area, which must have had some beneficial effect on keeping land rents lower throughout the urban area. Manhattan is special of course, but there has to be some "option values" effect from locations available just across the Hudson; locations available a few miles further inland; locations available a few miles further inland again; and so on until the fringe is reached. UK cities lack this advantage due to their fringe growth constraints, hence office rents in the centre of MOST UK cities, even small ones, are higher than those in Manhattan.

I would dispute, on the evidence, the claim that this difference is because Manhattan has built "up" while the UK cities have not. I would argue that the UK cities fringe constraints mean high rents in the city centre regardless of how much building "up" is allowed. The possible exception is if so much building "up" happens that it is literally an oversupply bubble. A crash would result in affordability for quite a few years afterwards. Something like this did happen to Manhattan in the 1930's, of course. The Empire State building was nicknamed the "Empty State" building for years.

For the record, as the

For the record, as the person who wrote the Seattle post:

First, totally on board with incremental growth, but it should be continuous, not the type of upzoning we see now where you end up with massive upzonings in some areas while others remain completely untouched. Allow duplexes and half-parcel homes, then in ten or fifteen years upzone again, perhaps to 3-story apartments. I don't have a specific plan for this because it's a big job, but the overriding point was that we're concentrating a lot of growth in a very small area and it's done almost entirely for the reason of "character preservation," which seems like a weak excuse given the scale of the challenges cities are facing.

As a side note, about half of the housing stock in Seattle is single-family, so in that case a slight upzone could actually make a massive difference.

Second, I think comparing these propositions to Le Corbusier, or places like Pruitt-Igoe, is exceptionally unfair and fundamentally mischaracterizes the argument. I've read enough of your writing to know you're aware that this isn't about a command-and-control government-led construction operation. It's about allowing developers to build when they deem a need, and they're very good at determining whether there's a need or not (generally speaking). Some single-family neighborhoods might, over the course of 30 or 50 years, turn into three-to-six story apartments maybe, yes. But as I wrote, many cities have a LOT of single family land and can afford to lose some. Maybe even more importantly, single family homes are usually owner occupied, so even if the residents lose the character they cherish -- a character I would cherish too, living so close to the city and still having a yard, garage, etc -- they get financially compensated. You can't say the same for the people who live in the areas that are currently being upzoned and redeveloped.

There is a lot to agree with

There is a lot to agree with here, and a few points to quibble with. Here are some thoughts, not all directed at Aaron who does excellent work.

Modern urban planning as a whole has a problem with discussing the built space, without enough thought towards the actual people involved. In my city of Portland this has led to a strange situation where it often feels like the planners are planning for theoretical people who don't live here yet, while dismissing any current residents who raise an objection as NIMBYs. Ironically, these current residents are the actual community, and the actual tax payers who employ these same planners and pay their salaries.

I often see this juxtaposition of emphasizing the built form vs. the people in discussions over gentrification. In a spirited comment section on gentrification, someone will inevitably say "why should the long-time residents of a 'bad neighborhood' complain if they're getting new coffee shops and less crime?" The answer is that many of them won't live there any more. So sure you've revitalized a place, but not for the people who have been there asking for the city's help. They've been displaced. So the improvements accrue to the physical place and gentrifiers, not to the neighborhood community as it existed before. (This is a simplification because many of the long-time residents are able to stay and are not displaced - but many are.)

A quibble would be over the argument that "there are many low-cost urban areas to live in." Those will often be the cities where there aren't jobs. The Bay Area has lots of good jobs. That's why people want/need to live there. "Move to Detroit and buy a old mansion!" is just as unrealistic as it sounds for 99% of people who have life elsewhere. Again, the "move somewhere else" arguments are often the result of depersonalizing urban planning and thinking of the residents as an afterthought or as little simcity bots.

Another issue is that everyone who talks about these issues in any forum has to internalize the fact that the Millennial generation is just in one life stage right now. It is VERY common to talk about them as if their current lifestyle choices will remain constant forever and should drive all urban planning policy.

Finally, we need to understand that humankind is diverse and there are all sorts of people with all sorts of preferences. I'd argue one of the main arguments against trying to turn every major city into Manhattan is that not enough people actually want to live that way. I don't want to live in high-rise housing and surveys show that most people agree with me. We need to stop treating people who choose to live in the suburbs or exurbs or small towns and rural areas like they "just don't get it" or like they would obviously prefer to live like us but just can't afford it. We need to accept the fact that they are free agents who know what they're doing and prefer it. The suburbs are there,and growing, because people want to be there and they will continue to want to be there.

Houston and Zoning

Houston does not have a formal zoning code. But it is a great myth that Houston has no land use controls. Both the city and county enforce a host of form based building ordinances. These ordinances regulate setbacks, maximum coverage on lots, parking and flood control. The ordinances are not the result of a unified plan but have come together over the years in response to various political, economic and environmental pressures.

Additionally, nearly all real estate development is controlled by deed restrictions placed on each parcel of property in Harris County. Deed restrictions circumscribe the use of a particular parcel. Deed restrictions run with the parcel from one owner to the next until they expire at some future date expressed in the restrictions themselves. In days of yore, they would expire and not renew unless a majority of residents in a sub-division voted to renew them. More recent developments automatically renew on a given date, unless a majority of residents of a subdivision vote to allow them to expire. The deed restrictions in my own sub-division ran for forty years from 1963 to 2003. They then renewed automatically, without protest, in 2003 and 2013.

Deed restrictions are the single greatest impediment to property re-development and densification in Houston and Harris County. The areas of Houston with the greatest amount of re-development and denser land use are those areas where deed restrictions have expired, without renewal, effectively leaving the property wide open for any new use.

Zoning

So I have heard that Houston has almost no zoning, and that seems to work out fine. Of course the city has few geographical restrictions and no history worth preserving, so that makes it easy. (Full disclosure: I've never been to Houston.) But eliminating zoning altogether would probably go a long way toward solving the problems Mr. Renn identifies in his article. Let people make their own decisions about what their neighborhoods look like. Of course sometimes they'll make bad decisions, but city governments and corrupt zoning boards are surely worse.