The world’s population recently passed the 7 billion mark, and, of course, the news was greeted with hysteria and consternation in the media. “It’s not hard to be alarmed,” intoned National Geographic. “We should all be afraid, very afraid,” warned the Guardian.

To be sure, continued population increases, particularly in very poor countries, do threaten the world economy and environment — not to mention these countries’ own people. But overall the biggest demographic problem stems not from too many people but from too few babies.

This is no longer just a phenomenon in advanced countries. The global “birth dearth” has spread to developing nations as well. Nearly one-third of the 59 countries with “sub-replacement” fertility rates — those under 2.1 per woman — come from the ranks of developing countries. Several large and important emerging countries, including Iran, Brazil and China, have birthrates lower than the U.S.

In the short run this is good news. It gives these countries an opportunity to leverage their large, youthful workforce and declining percentage of children to drive economic growth. But over the next two or three decades — by 2030 in China’s case – these economies will be forced to care for growing numbers of elderly and shrinking workforces. For the next generation of Chinese leaders, Deng Xiaoping’s rightful concern about overpopulation at the end of the Mao era will shift into a future of eldercare costs, shrinking domestic markets and labor shortages.

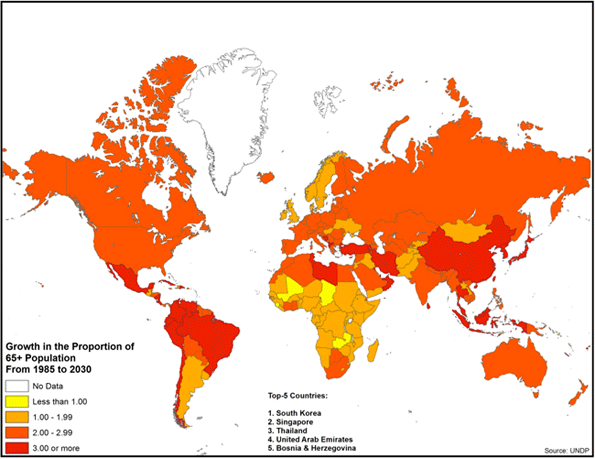

This scenario is already a reality in Japan and much of the European continent, including Greece, Spain, Portugal, much of Eastern Europe, Scandinavia and Germany. Adults over the age of 65 make up more than 20% of these countries’ populations — compared with 15% in the U.S. — and their numbers could double by 2030, according to researchers Emma Chen and Wendell Cox.

In many of these countries, rising debt burdens and shrinking labor markets have already slowed economic growth and suppressed any hope for a major long-term turnaround. The same will happen to even the best-run European economies, just as it has in Japan, whose decades-long growth spurt ended as its workforce began to shrink.

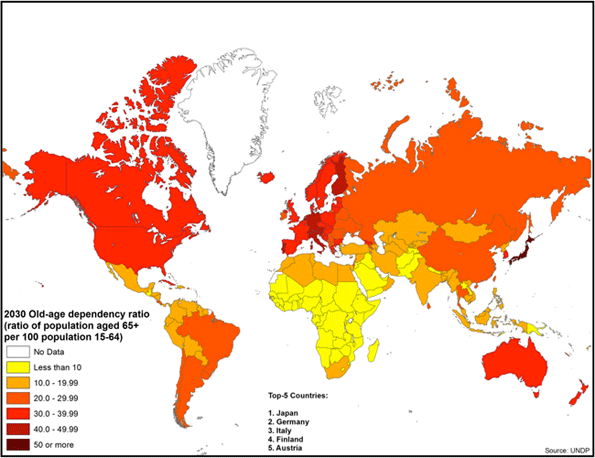

By 2030 the weight of an aging population will strangle what’s left of these economies. Germany, Japan, Italy and Portugal, for example, will all have only two workers for every retiree. The U.S. will fare somewhat better, with closer to three workers per retiree. By 2030 the median age will also be higher in China and Korea than in the U.S. This age difference will grow substantially by 2050, according to the Stanford Center on Longevity.

The biggest impact of aging, however, will not occur in northern Europe and Japan, where there may be enough chestnuts hidden away to keep the aged fed, but in Asia. In the next few decades, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand, and even Indonesia will start following Japan into the wheelchair stage of their demographic histories. These are not quite rich places like China and Brazil, which still lack the wealth and a developed welfare state to take care of the elderly Although not headed directly to European or Japanese rates of aging, these countries will experience a doubling of their Old Age Dependency Ratios; both will rise slightly above current U.S. levels by 2030.

In China, the one-child policy could be used to explain this phenomenon, but this hardly accounts for declining birthrates and rapid aging in countries such as Iran, Mexico or Brazil. Other factors — urbanization, a secular society and upwardly mobile women — also appear to be playing an important role.

Of course, the populations in most developing countries will still grow, but more due to longer lifetimes than a surfeit of new births. But projections are often wrong, and their demographic trajectory may slow down more than now predicted.

The one region expected to continue growing is Africa. Some countries, like Nigeria and Tanzania, are expected to more than double or even triple their current populations by 2050. But as Africa urbanizes and develops, it may eventually experience the same unexpected decline in fertility we already see in Islamic Iran, multi-cultural Brazil or throughout east Asia.

Largely left out of the analysis may well be the next big demographic phenomenon: the rise of childlessness. We have already seen how the move in developing countries from six kids or more per household has reduced population growth. In a similarly dramatic way the shift towards zero children, particularly in wealthier countries could have unforeseen lasting consquences. After all, with two children, or even with one kid, there’s the possibility of two or more grandchildren. With no children, it’s game over — forever.

Of course, there have always been unmarried people and childless people; some by necessity or health reasons, others by choice. But now a growing proportion of young child-bearing age women in countries as diverse as Italy, Japan and Taiwan are claiming no intention of having even one child. One-third of Japanese women in their 30s are unmarried, and similar trends are developing in other Asian countries.

Life without marriage, and children, has also become the rage among a large proportion of the cognoscenti even in historically procreation-friendly America. Whether it’s because men are seen as weak, or children too problematical, traditional families could erode further in the decades ahead.

The chidlessness phenomenon stems largely from such things as urbanization, high housing prices, intense competition over jobs and the rising prospects for women. The secularization of society — essentially embracing a self-oriented prospective — may also be a factor.

If this trend gains momentum, we may yet witness one of the greatest demographic revolutions in human history. As larger portions of the population eschew marriage and children, today’s projections of old age dependency ratios may end up being wildly understated. More important, the very things that have driven human society from primitive time — such as family and primary concern for children — will be shoved ever more to the sidelines. Our planet may be less crowded and frenetic, but, as in many of our child-free environments, a little bit sad and lot less vibrant.

Our future may well prove very different from the Malthusian dystopia widely promoted in the 1960s and still widely accepted throughout the media. With fewer children and workers, and more old folks, the “population bomb” end up being more of an implosion than an explosion.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

Photo "Nursery Cart" by flickr user Pieterjan Vandaele

Wonderful illustrated

Wonderful illustrated information. I thank you about that. No doubt it will be very useful for my future projects. Would like to see some other posts on the same subject!

neopaul.com

Thanks for this wonderful

Thanks for this wonderful post.Admiring the time and effort you put into your blog and detailed information.

here

Thanks for the post and

Thanks for the post and great tips..even I also think that hard work is the most important aspect of getting success..

Link Opener

Demographics

Demographic stability is always a problem. It is the story of human history.

Overpopulation is most definately the problem, unless you are suggesting that the ideal model of human living standards is India. Masses of people living in mega cities with every inch of land under human control and devoted to feeding the cities and supplying them with energy is a wonderful future. (Alternative energy systems will require more land than agriculture at some point.)

Everyone will have their little place to live in the hive and can sit on a bench in the sun 10 minutes a day when it is their turn.

Yes, exaggeration, but not too far from the truth. Too many people means no freedom to be a human animal and complete disconnection from any natural environment on the planet. Just a manucured park now and then.

Fortunately demographic trends are just peaking at the very top of the rollercoaster. The vast numbers of young people today will be old in 2050 and current birth rates will not provide enough new young people to support them then. There will be a mass die-off of human numbers (projected to be about 9.5b) mid century if the trends hold, if they are very lucky.

If education and learning continue maybe by 2100 a more sustainable and stable human population will be arrived at. A population around 3 billion with low birth rates and a higher quality of life for all.

One can dream.

Colin Clark classic tome

Colin Clark's magisterial tome "Population Growth and Land Use" (1967) should be a well known classic. It is a sad indictment on our post-rational era that it is not, as a consequence of Clark's anti-alarmism on population growth.

Clark was possibly more famous while he was alive:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colin_Clark

He was highly respected by Keynes, even though a frequent opponent; Keynes changed his position on population and growth in a once famous address to the Francis Galton Society (a eugenics think tank) after being persuaded by Clark.

Colin Clark (back in 1977): “Exploding Population Myths”

Colin Clark: “Exploding Population Myths”

The Annual Monash Memorial Lecture, 1977

“The simple method of judging the trend of population by comparing current births with current deaths is open to an objection so obvious that many people fail to see it, namely, that while current births relate to the present generation of parental age, current deaths relate on the average to the much smaller generation born some seventy years ago. If current deaths are equal to current births, therefore, this must mean that population in the future is certain to decline. Now we are facing depopulation.

World power depends, even more than it did in the past, on having a large population, not primarily in having large numbers of recruits to the armed forces; but principally in having sufficient taxpayers to pay for the enormously costly equipment which modern armed forces require.

The cause of our infertility must be sought, it seems, in our social psychology, in a profound disillusion with the civilisation in which we live. People will undertake the undoubted hardships and difficulties of bringing up children if they have firmly fixed in the backs of their minds the belief that there is something good in the civilisation in which they live, that they live in a world worth bringing children into.

All previous civilisations have had a faith by which they lived. We have almost entirely lost ours, and are becoming totally disillusioned with our civilisation.

When I said at a public session of the ANZAAS 1976 Conference in Hobart that these declines in reproductivity, if not checked, would bring our civilisation to an end, a substantial part of the audience indicated by their applause that they thought that this was a desirable objective.

Another observation to be made of civilisations in decline is that they are becoming increasingly bureaucratic and overtaxed. Governments, even more than businesses, tend to have high overhead costs, i.e., those which show little or no alteration with the size of the population which they have to serve. A stationary or declining population thus increases the comparative burden of government expenditure. It also increases the temptation on governments, faced with difficulties in raising money by taxation or borrowing, to try to get out of them by inflation.

It is significant that France, which for a long period has had an almost stationary population, since the nineteenth century should have suffered more persistent devaluations than most Western countries.

It can only be some irrational force of social psychology at work which led such large numbers of supposedly rational people to accept with enthusiasm the obvious nonsense about the prospect of the immediate extinction of our industrial civilisation through the exhaustion of mineral and agricultural resources; while at the same time being overwhelmed by pollution. If such people really believed what they were saying, they would have bought agricultural land and mining shares, both of which would obviously be rising rapidly in value if the world really were on the point of exhausting its resources……”

http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/clark_colin_population.html