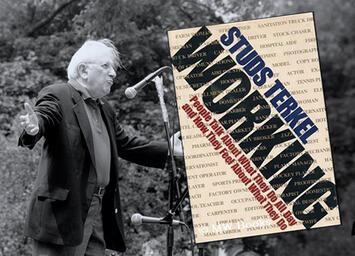

As I prepared to teach my module on work this year, I realised that Studs Terkel’s book Working celebrates its fiftieth anniversary in 2022. It’s a book that both reflects and helps to explain working-class life. I first encountered it as a student, and in the passing years Working — or to give it its rarely used full title Working: People Talk About What they Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do – has shaped profoundly the way I think and teach about work.

First published in January 1972, Working is a baggy collection of over seven-hundred and sixty pages, most devoted to the reflections of ordinary Americans about their economic lives. From the Terkel archive, it’s clear that his interest in work was long standing and went well beyond the USA.

I know the book well, but in writing this piece I leafed through it again to think about the changing nature of work across that half a century. I thought it might really be showing its age — after all, fifty years is a long career. Instead, I was reminded how vital Working is. To my surprize, many of the jobs and occupations Terkel asked about in his interviews still exist: receptionists and police officers, spot welders and carpenters, factory owners to waitresses and so on. For sure, the technology that workers use in their jobs has changed. Few of the people in the pages of Working in 1972 would have seen a computer, less likely used one. But it’s harder than you might think to see obsolescence here.

Working remains fresh because Terkel’s humanity and warmth comes through on virtually every page. His character as well as his approach to the art of interviewing are artfully captured in his introduction. Just seventeen pages long, the essay sums up for me what is most important about work – people. As he puts it beautifully:

It’s about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying. Perhaps immortality, too, is part of the quest. To be remembered was the wish, spoken and unspoken, of the heroes and heroines of this book.

Terkel captures the timeless quality of the profound contradictions of work, especially a worker’s sense of loving and hating work in the same moment. This may be true of all kinds of work, but it seems especially important in working-class labour. In an interview about Working, Terkel described how a meter reader he talked to spoke about the reality and fantasy of his work. While reality demanded that he be constantly vigilant for dogs, he also fantasized about female encounters on his rounds. As Terkel puts it, ‘it makes the day go faster’.

Read the rest of this piece at Working-Class Perspectives.

Tim Strangleman, Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent, is a Contributor to Working-Class Perspectives.

Photo credit: Newberry Library, via Wikimedia under CC 4.0 License.