One cornerstone for urban designers and planners seeking to transform the polycentric or suburban city of the 20th Century into something resembling the high density city of the 19th was a cross-city comparison by Newman and Kenworthy and successors. [1] They argued that this proved automobile dependence is a function of city density. It followed that regulating for greater residential densities and increasing the capacity of public transport systems to avoid the congestion that would follow if people continued to drive themselves would improve the sustainability of cities.

Of course, any comparison with the overcrowded and unhealthy cities of an earlier century is unfair: today’s density is achieved with higher standards of private and public space, and much enhanced transit and sanitation. And many, probably the majority, of 21st century citizens in high income nations can escape the confines of the urban environment on occasional sojourns to country or coast (or beyond), unlike their 19th Century or developing world counterparts. They can even find repose in the midst of 24/7 city hubbub in their own in-house media centres.

But can we really build urban policy on the Newman and Kenworthy analysis? Especially given evidence that car use is declining anyway?

Questionable correlation

There are still questions over the original analysis and it successors. Cross-cultural effects, physical geography, differences in economic structure, incomes, wealth, and growth all intervene in the relationship between city density and car dependence. And cause and effect are hard to pin down.

Perhaps more critical: the leap from observing relationships across cities at a point in time to regulating travel behaviour, housing ,and consumption choices into the future assumes that individual behaviour is a microcosm of collective behaviour. This fallacy of inference has long been recognised by the biological and sociological sciences. And the likelihood of getting policy wrong by making such an assumption is far greater when dealing with populations of people, with their diverse circumstances, beliefs, values, and means, compared with, say, populations of penguins.

Is it this blind spot that has made it so much more difficult to get people out of their cars or their low density houses than anticipated by urban reformists?

The city as a time warp

One problem is that analyses of city density and car dependence are usually static. Plotting urban form and transport consumption at a particular point in time – the mid/late 20th century in the Newman and Kenworthy case – embodies particular patterns of technology, wealth, and behaviour. Consequently, their urban prescription is based implicitly on the 9 to 5 work day; single city centres that focus urban employment, exchange, and consumption; and the nuclear family with its distinctive housing and service demands. These are all urban artifacts that have been breaking down since the 1960s.

But the times they are a-changing

In a 2011 paper the authors acknowledge that things are changing as international evidence shows rates of car use beginning to decline in parts of the world. A partial view of what they are changing from, though, sustains a deterministic explanation of the why and what they are changing to:

“technological limits set by the inability of cars to continue causing urban sprawl within travel time budgets; the rapid growth in transit and re-urbanization which combine to cause exponential declines in car use; the reduction of car use by older people in cities and among younger people due to the emerging culture of urbanism and the growth in the price of fuel which underlies all the above factors”.[2]

The view remains time-bound; even the reference to exponential decline is a simplistic inference of the relationship between public transport and car use taken from a cross section of cities in 1995.

Individual agency barely gets a mention. Any description of an “emerging culture of urbanism” needs to be embedded in the reality of evolving patterns of wealth, income, and consumption and even in simple demographics to determine just how real and significant it is.

Growing old and driving more

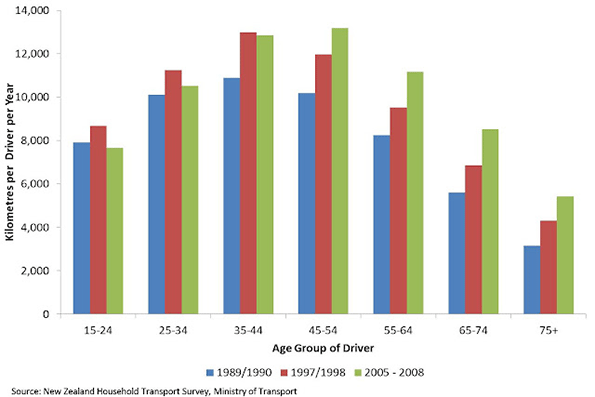

What are the grounds for the claim that older people are reducing their car use, for example? I took a quick look at the evidence for New Zealand. It is certainly not the case here. The rate of growth in driving has been higher among older age groups than among younger – with decline most evident among the under 45s.

Is it so different in the other ageing societies from which Newman and Kenworthy draw their examples?

Figure 1: Changes in Annual Driving Distance by Age, New Zealand 1990-2008

Fewer kilometres doesn’t mean less dependence

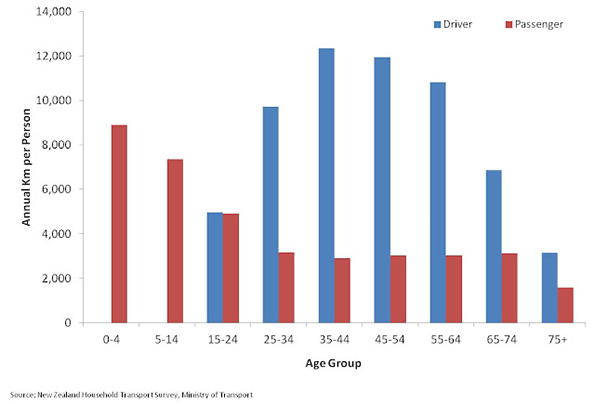

What does go a long way to explaining declining car travel in the aggregate is the fact that older people don’t drive as much younger people, and populations in western cities are simply getting older. It’s simple maths – as the population ages car usage will go down, despite a greater propensity to drive among older cohorts. Again, look at the evidence from New Zealand:

Figure 2: Automobile Dependence by Age Group, New Zealand 2004-2008

Car usage appears to decline after age 44, rapidly after retirement age, 65.

Why does car use fall with age?

There are a number of reasons why this may be so. From 45 years on households have fewer transport-dependent children. Mature families may have more localised social networks. A greater share of recreation may be neighbourhood based.

On retirement work trips disappear and incomes, discretionary dollars and consumption fall. The capacity for more shared travel and trip planning increases as households age. Diminished car use doesn't necessarily mean that households are less automobile dependent. They just doesn’t generate as much travel demand.

These explanations don’t depend on particular urban designs. Yet Newman and Kenworthy claim that diminished driving happens because “older people move back into cities from the suburbs”. This is not consistent with the common observation of people’s preference to age in place.[3] (For the New Zealand evidence, see my posting Ageing in the City).

Moving into the centre - a one-way street?

And their notion “the children growing up in the suburbs would begin flocking back into the cities rather than continuing the life of car dependence” rather simplifies a historically specific event: the transition of sons and daughters of the baby boomers from young adulthood, advanced education, and job seeking to the career and housing paths associated with their movement into more stable relationships. As they age, it is highly likely that suburban preferences re-emerge, sustained by the capacity to purchase and operate a private vehicle.

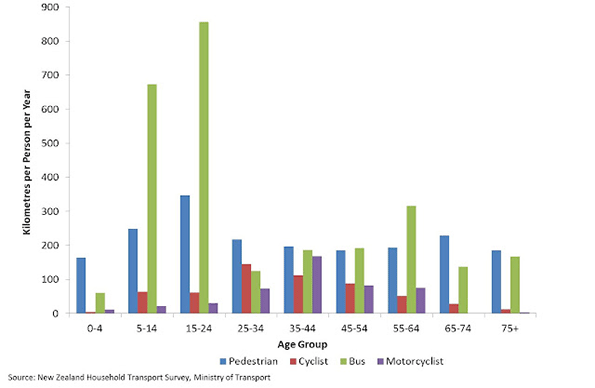

Generation X boosted inner city dwelling over the past two decades, and Generation Y will do so, to a lesser extent, for another decade. The 15 to 24 year age group also coincides with the age of greatest automobile independence (illustrated for New Zealand in Figure 3). But don’t expect this historically-specific phenomenon to sustain some sort of indefinite culture of city consolidation, and I wouldn’t bet the fiscal bank on expensive transit systems designed around the assumption that it will.

These are passing generations: their successors will be that much smaller and facing a somewhat different world.[4]

Figure 3: Use of non-Automotive Modes by Age Group, New Zealand 2004-2008

Who are we planning for?

Of course, there are plenty of exceptions to prove the rule: but that is the point. Diverse communities have diverse expectations and behaviours. And they are continuously changing, in composition, in form, and in behaviour.

The failure of modernity lay in its assumption of conformity and convergence, compounded by the conceit that we could regulate for it. And planning for what is little more than a statistical construct – the auto-independent city – risks blinding us to the richness and opportunity of alternatives, of lifestyle, of environmental stewardship, of urban design, and of mobility.

If we start with the behaviour of individuals and households our designs for sustainable cities may be less deterministic and our planning less didactic, better informed, lighter in touch, and a lot more effective in meeting the long-term needs of evolving urban communities.

Phil McDermott is a Director of CityScope Consultants in Auckland, New Zealand, and Adjunct Professor of Regional and Urban Development at Auckland University of Technology. He works in urban, economic and transport development throughout New Zealand and in Australia, Asia, and the Pacific. He was formerly Head of the School of Resource and Environmental Planning at Massey University and General Manager of the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation in Sydney. This piece originally appeared at is blog: Cities Matter.

Aukland photo by Bigstockphoto.com.

[1] Newman, P and Kenworthy J (1989) Cities and Auto Dependency: A Sourcebook. Gower, Aldershot

Newman, P and Kenworthy, J Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence, Island Press, Washington, D.C.

[2] Newman P and Kenworthy J (2011) “‘Peak Car Use’: Understanding the Demise of Automobile Dependence”, World Policy Transport and Practice, 17, 2, 31-42

[3] Pynoos R, Caraviello R, and Cicero C (2009) “Lifelong Housing: The Anchor in Aging-Friendly Communities”, Journal of the America Society on Aging, 33, 2, 26-32

[4] For New Zealand, check the numbers

One cornerstone for urban

One cornerstone for urban designers and planners seeking to transform the polycentric or suburban city of the 20th Century into something resembling the high density city of the 19th was One Piece watch online a cross-city comparison by Newman and Kenworthy and successors. [1] They argued that this proved automobile dependence is a function of city density. It followed that regulating for greater residential densities Skip Beat manga comics and increasing the capacity of public transport systems to avoid the congestion

Adopting latest technology

Adopting latest technology is the fashion of everyone in this era. The advanced technology makes our tax more reliable and flexible. The uses of car has no limitation, the main purpose of a car is to journey or transformation.

But now peoples use a car for maintain the life style, spend a luxurious life, as an entertaining element beside its main purpose. Not only the audio systems but also a latest audio system with having advanced feature becomes an essential part for a car owner.

BMW Repair Arcadia

People are more interested

People are more interested in using different gadgets than using the same old gadgets repeatedly. Day by day people are not interested in using cars as because they are no more dependent on cars. the cities are also getting more crowded due to more number of people.

Audi Repair Dallas

In today's world the density

In today's world the density of car users are rapidly increases especially in urban cities; we have witnessed people are using cars for their daily works such as travel from one place to another. Therefore the range of driving grows every year.

http://www.hamiltonscarservice.com/areas-served/

Changing Car use ignores new technology

Generally an excellent and relevant article. But, it ignores what a few people are doing to invent better ways of getting around, beyond conventional buses and trains. Many examples can be found around the world today. Some are fully automated, others are partially automated, some are operational, some are being developed and tested and others are still conceptual. Most are struggling as their visibility is low and their development funds have been and are quite limited. And the conventional industry wants nothing to do with them. Three are now market-ready and are in operation in the U.K., Sweden and the Masdar eco-city in Abu Dhabi. The latest project is going forward in Amritsar, India, expected to accommodate 100,000 visitors per day at their golden temple. Details may be found by googling Innovative Transportation Technologies.

Articel needs a re-write

This article needs a good editor.

Its style is "academic turbidity".

Clarity and plainer English would help.

Dave Barnes

+1.303.744.9024

Academic rigour

Cross out the 'academic' I'd say. This is a prime example of opinion rather than trustworthy research.

Phil criticizes Newman and Kenworthy's reliance on the 'ecological fallacy', and then promptly uses exactly the same method (takes aggregated data from a census, and infers individual behaviours) to justify a contradictory review.

Poor.

FWIW, I agree with Phil that it is, in reality, individual behaviours and choices that matter, rather than disconnected policy postures and prescriptions for urban planning. Unfortunately Phil seems very dismissive of the individual changes in preference that appear to be taking place on a widespread basis.

Talking to anyone in the age categories Phil focuses on (broadly, young, mid and old aged) reveals some strong shifts in preference that are enduring through the 'traditional' barrier of family formation/middle age, where the inflexion in Phil's data charts occurs. In short, hiding behind this data continues to ignore real (individual) social change.

Head in the sand, hoping for a continuity of the old twentieth century thinking.

Tim Robinson

Architect & Urban Designer, Auckland, NZ

Clarity

Fair comment. How about this?

Over time people are travelling more and driving cars further. But at any one time older people travel less. As the population is ageing, the second effect is beginning to outweigh the first. The result is that car use is diminishing because communities are ageing, not because we are forcing people out of cars by planning policies that impose higher urban densities.

Cars are integral to modern

Cars are integral to modern life. They dominate household economies too: aside from rent or mortgage payments, transport costs are the single biggest weekly outlay, and most of those costs normally come from cars or from when you donate a car.

Car uses differ

Car uses differ from rural areas as comparison to urban areas . The use of vehicles in urban areas is more as in comparison to rural areas. Rural areas villagers people are having many problems like way of communication is very bad. Roads are very rough, no vehicle repairing center etc. Audi Repair Woodland Hills