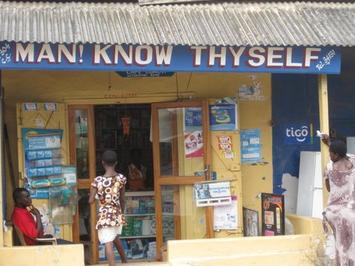

For the past week an irritating little tune has bounced into my head unexpectedly every time I turned to news about the financial collapse. The melody would then remain at the edge of my consciousness for hours at a time like a buzz or a hum in my ear. Though I couldn’t make out the lyrics, I could distinguish the distinct nasal whine that Rex Harrison affected in the musical My Fair Lady. Still, I couldn’t pin down which song was playing on an endless loop in my head. Instead, as I made my way through the Kotokuraba Market in Cape Coast, Ghana, this past week, I found myself absentmindedly substituting my own lyrics to the Frederick Loewe score. At first I sang the line “If only Lehman Brothers was more like the Man! Know Thyself Pharmacy,” and then “If only AIG could be more like Is Not By Might Alone Construction.” Though my feeble attempt did not come close to scanning, I knew immediately that I was onto something. There was a nugget of truth there that I could never have reached through ordinary means of logical analysis. I began to rattle off all the financial behemoths who have crashed or have nearly crashed or will potentially go belly up in the coming months, giants like Merrill Lynch, Citibank, Wachovia, Washington Mutual—the list seems to grow with every passing day.

I continued to substitute the strange names for businesses that Ghanaians seem to prefer for those of the failing financial industry. After my initial amusement of replacing Lehman Brothers with Man! Know Thyself, I realized that the way businesses are named in Ghana speaks to core values that perhaps would have kept the Wall Street CEOs in check. Ghana is a country steeped in the oral tradition of proverbs. The ancient Akan religion is full of proverbs and sayings about how to live a moral and upright life. Surprisingly, most of these Akan tribal proverbs correlate directly to Christian proverbs despite the fact that they existed long before Europeans introduced Christianity to the region. As a result, these sayings have remained a vital part of the culture and often crop up in conversation in a kind of abbreviated shorthand. On the street conversation is peppered with such statements: “But, I have forgiven you, let us not bite one another,” “So you strike fire among us ever,” “Oh great ancestors, our blood relation chain will never break apart,” “Till death ladder, together we climb to rest,” among scores of others. Since Ghana is a public and communal society unlike Western cultures which are more private and personal, these sayings and expressions of philosophies and beliefs tend to affirm a responsibility toward others.

I’ve been particularly moved by the name of a small hardware store, “But Like A Chain Ventures,” which is an abbreviation of the Akan proverb “But like a chain, we are linked both in life and death with our people, because we share common blood relations.” As I reflected on the implications of Lehman Brothers being named “But Like A Chain Investment Bank,” I tried to tease out the implications of such a dramatic change in the strategy of naming businesses in most of the Western world. American businesses appear to emphasize ownership, especially in advertisements and product names employing the notion “this is mine”, rather than their moral and ethical relationship to customers and the community. In recent years this has played out intricately in such marketing strategies as “branding.” For Ghanaians, business names are more a form of moral or ethical expression. Names are an opportunity to publicly articulate a belief or philosophy. Because Ghana is such a public and communal society, the way you present yourself is much more important than the product you are offering. Customers are drawn to businesses that express the mores of the community first, and then they determine whether the business offers what they are looking for. In a community where politeness is primary, knowing the kind of person you are doing business with first is a determining factor greater than price, location, or variety.

With this in mind, I now wonder if such a name would not have stopped this fallen bank’s former CEO Richard S. Fuld Jr. and his brethren from pursuing personal gain to such a degree that the entire globe was at risk. Would the message printed on the stationary and on the front of the building have been sufficient to caution their recklessness? Probably not, but it is nice to consider such a possibility.

On October 9th, 2008, the Washington Post reported that even the International Monetary Fund, the world’s cheerleader for world markets, has now qualified its support. "Obviously the crisis comes from an important regulatory and supervisory failure in advanced countries […] and a failure in market discipline mechanisms," Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the IMF's managing director, told the Post. She emphasized that African countries with the least free market openness are more prepared than most to survive a major global recession.

Like most African economies, Ghana is primarily a cash society. The average person on the street, even if he or she has a job, cannot get credit and would never consider attempting to get a loan. No one has a Visa card here because no businesses accept them. When my friend, the playwright Victor Yankah, had to pay his middle son’s college tuition at the beginning of September, he took out a six inch thick stack of ten and twenty cedis from his bank account to pay the university’s 5,000 Ghana cedi fee. As the economic crisis intensifies, Yankah feels prepared because he has diversified the African way. His wife Betty Yankah owns a small dry goods stall in the local market. In addition to being head of the Department of Theater Studies at the University of Cape Coast, Yankah also owns a small orange grove that supplies fruit to local markets as well as a fish hatchery along the Volta River. He has positioned himself to “think globally and act locally.” He hopes that by staying close to the ground he and his family will weather whatever dire economic times lie ahead.

As I play with renaming the failing titans of finance, the reference I have been trying to remember finally comes to me. The song I am thinking about is “A Hymn to Him,” a solipsistic and misogynist diddy asking, “Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” I can imagine Lehman’s fallen CEO Fuld Jr. singing a similarly written ode to free market capitalism and self-aggrandizement. To which, I would counter: Why can’t Wall Street Be More Like Ghana? And this verse scans.

Laban Carrick Hill is a visiting professor at University of Cape Coast in Ghana and the author of more than 25 books, including the 2004 National Book Award Finalist Harlem Stomp! A Cultural History of the Harlem Renaissance. His most recent book America Dreaming: How Youth Changed America in the 60's

recently won the 2007 Parenting Publications Gold Award.

Didn't you believe that

Didn't you believe that woman can do what man can? It’s just a matter of perseverance, sympathy and hard work. Aren't you aware that the latest pharmacy school ratings, women is in the top list? Women can do better than men, they can stand without men. As the saying that goes, “In every man’s success, there is always a woman behind”? I believe in that and this proves something to me.