Over time, suburbs have had many enemies, but perhaps none were more able to impose their version than the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In its bid to remake a Russia of backward villages and provincial towns, the Soviets favored big cities – the bigger the better – and policies that were at least vaguely reminiscent of the “pack and stack” policies so popular with developers and planners today.

Some of this took the form of rapid urbanization of rural areas. Under Joseph Stalin’s rule in the Soviet Union from 1929 to 1953, scores of “socialist cities” were founded near new, expansive steel mills. These steels mills were built to speed up industrialization, in order to produce vast amounts of weaponry. These, notes historian Anne Applebaum, represented the Soviet communists “most comprehensive attempt to jump-start the creation of a truly totalitarian civilization”, by bringing the peasantry into the factories to grow Russia’s working class. Built from the ground up, these factory complexes, notes Applebaum, “were intended to prove, definitively, that when unhindered by preexisting economic relationships, central planning could produce more rapid economic growth than capitalism”.

As is sometimes asserted by urbanists today, the new socialist cities were about more than mere economic growth; they were widely posed as a means to develop a new kind of society, one that could make possible the spread of Homo sovieticus (the Soviet man). As one German historian writes, the socialist city was to be a place “free of historical burdens, where a new human being was to come into existence, the city and the factory were to be a laboratory of a future society, culture, and way of life”.

Elements of High Stalinist culture was evident in these cities; the cult of heavy industry, shock worker movement, youth group activity, and the aesthetics of socialist realism. This approach had no room for what in Britain was called “a middle landscape” between countryside and city. Throughout Russia, and much of Eastern Europe, tall apartment blocks were chosen over leafy suburbs. Soviets had no interest in suburbs of any kind because the character of a city “is that people live an urban life. And on the edges of the city or outside the city, they live a rural life”. The rural life was exactly what communist leaders hoped their country would get away from, therefore Soviet planners housed residents near industrial sites so they could contribute to their country through state-sponsored work.

With this assumption, Soviet planners made some logical steps to promote density. They built nurseries and preschools as well as theatre and sports halls within walking distance to worker’s homes. Communal eating areas were arranged. Also, wide boulevards were crucial for marches and to have a clear path to and from the factory for the workers. The goals of the “socialist city” planners were to not just transform urban planning but human behavior, helping such spaces would breed the “urban human”.

As is common with utopian approaches to cities, problems arose. Rapid development, the speed of construction, the use of night shifts, the long working days, and the inexperience of both workers and management all contributed to frequent technological failures. Contrary to the propaganda, there was a huge gap between the ideal of happy workers thriving in well-managed cities and the reality.

If today’s architects sometimes obsess over the quality of production and design, the Soviet campaign to expand dense urbanism was less aesthetically oriented. Less than a year after Stalin’s death, in December 1954, Nikita Khrushchev set a campaign to promote the “industrialization of architecture”. He spoke highly of prefabricated buildings, reinforced concrete, and standardized apartments. He did not care for appearances, instead focusing on just building housing because that is what the people need. Prefab tower blocks, called Plattenbau in German and panelaky in Czech and Slovak, were constructed all over the Soviet Union and their satellite states. Originally, these apartments were to house families working for the state.

In 1957, a group of architecture academics from the University of Moscow published a book called the Novye Elementy Rasseleniia or “New Elements of Settlement”. This team of socialist architects and planners --- Alexei Gutnov, A. Baburov, G. Djumenton, S. Kharitonova, I. Lezava, S. Sadovskij--- became known as the “NER Group.” In 1968, they were invited to the Milan Triennale by Giancarlo de Carlo to present their plans for an ideal communist city. In cooperation with a group of young urbanists, architects, and sociologists, they created an Italian edition of their book under the title Idee per la Citta Comunista.

Alexei Gutnov and his team set to create “a concrete spatial agenda for Marxism”. At the center of The Communist City lay the “The New Unit of Settlement” (NUS) described as “a blueprint for a truly socialist city“. Gutnov established four fundamental principles dictating their design plan. First, they wanted equal mobility for all residents with each sector being at equal walking distance from the center of the community and from the rural area surrounding them. Secondly, distances from a park area or to the center were planned on a pedestrian scale, ensuring the ability for everyone to be able to reasonably walk everywhere. Third, public transportation would operate on circuits outside the pedestrian area, but stay linked centrally with the NUS, so that residents can go from home to work and vice versa easily. Lastly, every sector would be surrounded by open land on at least two sides, creating a green belt.

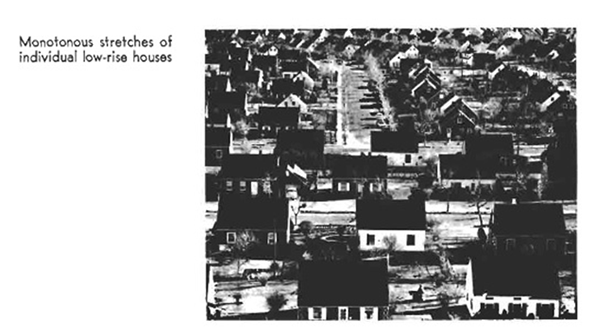

Gutnov did acknowledge the appeal of suburbia --- “…ideal conditions for rest and privacy are offered by the individual house situated in the midst of nature…”, but rejected the suburban model common in America and other capitalist countries. Suburbs, he argued, are not feasible in a society that prioritizes equality, stating, “The attempt to make the villa available to the average consumer means building a mass of little houses, each on a tiny piece of land. . . . The mass construction of individual houses, however, destroys the basic character of this type of residence.”

The planner’s main concern was ensuring social equality. This was seen in their preference of public transportation over privately owned vehicles, high-density apartment housing over detached private homes, and maximizing common areas. These criticisms of suburban sprawl have some resonance in the writings by planners advocating “smart growth” today. Both see benefits to high density housing. For one, they argue it is more equitable so everyone, no matter what social class they belong too, can live in the same type of buildings. Some New Urbanists do also like the idea of mixed-income communities. In addition, they both see their ideal community utilizing mixed-use developments, with assuring people easy access to public services such as day care, restaurants, and parks, creating less of a need for private spaces. Similarly, New Urbanists also claim that their planned developments would foster a better sense of community.

Source: Gutnov, Alexi, Baburov, A., Djumenton, G., Kharitonova, S., Lezava, I., Sadovskij, S. The Ideal Communist City. George Braziller: New York. 1971.

Of course, it is easy to go too far with these analogies. Even at their most strident, new urbanists and smart growth advocates do not enjoy anything like monopoly of power than accrued to Communist leaders. And also, not all the ideas of new urbanists, and even the creators of the Ideal Communist City, are without merit. The ideas of walkability, close access to amenities and services, are adoptable even in privately planned, suburban developments. But the dangers of placing ideology before what people prefer are manifest, whether in 20th Century Russia or America today.

Alicia Kurimska is a research associate at the Center for Opportunity Urbanism and Chapman University's Center for Demographics and Policy. She is the co-author of "The Millennial Dilemma: A Generation Searches for Home... On Their Terms" and deputy editor of New Geography, a website focusing on economics, demographics, and policy."

Lead photo of Krushchev-era apartment buidlings in Estonia, "EU-EE-Tallinn-PT-Pelguranna-Lõime 31" by Dmitry G - Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Monitoring the workers

Don't forget another major advantage of high-density housing. It makes it far easier for spies to keep an eye on these workers.

Also, as those who designed Paris readily admitted, wide boulevards running at an angle to the normal street grid make it easier for a few strategically placed troops with cannons to control movement about the city.

Government spies and military control

Yes, the East German Stasi and Stalin era internal spies were everywhere. And yes, the grand boulevards of Paris were carved out of the jumbled chaos of narrow Medieval streets by Haussmann and Napoleon in part to consolidate military control over the population.

The current equivalent is drones and internet data mining - Conservatives worry about Big Government, liberals worry about Corporate America, but they're one and the same. If you don't think drones are (or soon will be) monitoring your house in the suburbs you're not paying attention.

www.granolashotgun.com

Good point

Thank you for pointing this out: you beat me to it.

Ironically now that Russians have been flocking to driving since they had the freedom to do so, these street networks are better than what an entire city that is a "TOD" could have been expected to be.

I noticed in a UN report on cities street network intensity, that Moscow and Auckland NZ have approximately the same street network intensity. At the bottom of the pack, admittedly, and to Auckland's shame; but you will get what I mean.

Commie Condos

Yeah, I knew instantly that the lead photo wasn't Moscow or Kiev. It looks much more like the "Little Russian" commie condos from Riga or one of the other more prosperous satellite states. The ones in bigger cities were just that much more hideous. Somehow the Baltic republics managed to tone things down and make them more... Swedish. "Socialist" rather than full on communist. Like the building in the photo many of these Eastern European Soviet era apartment blocks are getting scrubbed clean, renovated, given fresh paint and landscaping, and are pressed back into service. Tearing them down and building split level ranches on cul-de-sacs would be too expensive... On the other hand, everyone had a dacha and their six sotok which were pretty damned charming in their own way.

I do marvel at how Las Vegas builds exactly the same massive concrete tower blocks, puts in some tacky carpet and wall paper and faux Italian tchotchkes and suddenly it's a capitalist consumer playground. It's the same exact crap architecture. What's the big diff? You think any of those buildings were lovingly hand crafted to last for centuries? Been to Atlantic City lately? Feh!

On a similar note, have you been to a Costco or Walmart in recent years? It looks like the Pavilion of Economic Achievement in there. I'm just sayin'. Ugly centrally planned concrete bunker architecture is universal. All the empires love it.

www.granolashotgun.com

Freedom of choice wins even if some of it upsets elitists

Oh come on, in the examples you give, that is just a fraction of the overall urban area's development, there is a wide variety and people get to choose. The whole point about Communism is it was top-down planning of an approved outcome for everyone. No-one forces anyone to live in a tower in Vegas or shop at Costco.

I also recommend to everyone, Alain Bertaud's papers "The Cost of Utopia" and "Cities Without Land Markets".

The intentions stated in the article above were never remotely realised, as growth was provided for by adding taller and taller apartment blocks further and further away along radial rail routes, resulting in greater and greater inefficiencies of average travel time and expense.

But ironically, even in dense cities with functioning land markets, average commuting times tend to be outliers on the high side. It is a total myth that many people at all in, say, Hong Kong, catch an elevator down to the ground floor, stroll along the road a bit, and catch an elevator back up to their job. Their average commute time (one way) is 47 minutes. Tokyo and London are similar outliers. There are no such outliers among lower density cities, contrary to the myths, propaganda and outright lies from the opponents of "sprawl".

Even in the UK's low but crowded and high density cities (5 times US densities on average) the average commute time is 50% higher than the US's average commute time.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/3085647.stm

“British commuters have the longest journeys to work in Europe with the average trip taking 45 minutes, according to a study. That is almost twice as long as the commute faced by Italians and seven minutes more than the European Union average…..”

The US average is 26 minutes.

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/14/world-of-commuters/

There is obviously something inherently inefficient and distorted about urban land markets with strict containment of density regulations.

Top down housing policy

There are two issues here. Let's separate them.

First, some people really prefer living in a single family home with a front lawn and a back garden and would much rather drive a private car. Other people actually enjoy apartment living and would rather hop on a bus or train. To each his own. It's a big county. There's room for everyone.

Second, there's the question of top-down state planning and control that limits those choices. In Soviet era Eastern Europe the only buildings that were built were state owned apartment towers organized around public transit. This reflected the Communist ideology that everyone was equal like bees in a hive all working to build the Communist utopia. Single family homes with a garden were a manifestation of evil capitalist bourgeois values.

But let's examine the post WWII American suburb. It too is top down and centrally planned. Federal, state, and municipal zoning, building codes, and mortgage lending standards explicitly enforce single family home development and rigid separation of uses in order to maintain a very specific set of cultural and social arrangements to the exclusion of all others. Try and convert your single family home into a duplex. Illegal. Try and run a small businesses out of your home. Illegal. Try and build a granny cottage in your quarter acre back yard. Illegal. Try and convert a shop in a strip mall into a live/work situation. Illegal. There are even strict rules about how often you can have a garage sale. Car ownership is de facto mandated because no one can physically function in suburbia without one. This isn't an accident. It's by design. It's a myth that America is the Land of the Free where private property rights are sacrosanct. We're all very much limited in what we can do in our own homes - for the common good.

Argue about which values are better, but don't pretend anyone has a choice when it comes to conforming in either system.

www.granolashotgun.com