Shortly after my piece on Phantom Bonds, Blame Wall Street's Phantom Bonds For The Credit Crisis, posted here on NewGeography.com in November, a friend called from New York to ask if I’d seen the latest news. Bloomberg News reported on December 10 that “…The three-year note auction drew a yield of 1.245 percent, the lowest on record... The three-month bill rate [fell] to minus 0.01 percent yesterday.” The US Treasury is seeing interest rates on its notes that are “the lowest since it started auctioning them in 1929.”

My friend is an intelligent person, a lawyer who managed to accumulate more than $1 million working a 9-to-5 job in a not-for-profit firm and retire in her 50s. Some of her portfolio is in Treasury bonds, so she had a lot of questions. In the course of our conversation, it became clear that I wasn’t going to be able to explain all she needed to know on the phone, despite her background. I decided to write this short owner’s manual.

Here’s how it works, and how it ties back to the problem of phantom bonds. When the US government needs to raise money it authorizes its agent, the Federal Reserve Bank (FRB), to sell securities. The different names for these securities are associated with how long they will remain outstanding, like the term of a loan: bills are up to 1 year, notes are up to 7 years, and anything longer than that is a bond. We’ll just call them bonds to make it easy.

The FRB has relationships with several primary dealers like Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and Morgan Stanley. When notifications are sent out that some bonds will be sold, these primary dealers submit bids in the form of prices. If a financial institution bids $99 for a $100 bond, then that bond will essentially pay - or ‘yield’— roughly 1% from the US Treasury (UST) to its holder. If the investor bids $101 for the $100 bond, then it will pay 1% for the privilege of lending money to the UST; the bond’s ‘yield’ would then be minus 1%. That’s a very good thing if you happen to be the UST, which of course we all are because it’s all taxpayer money.

So— as the prices of bonds rise, the yields fall, and these yields translate into the interest rate that the UST pays to the bondholders in order to borrow the money it needs to fund the budget deficit (and to refinance the existing national debt).

This is all roughly speaking, of course. But the idea is that the interest rates are set based on the prices that are bid in something that’s like a blind auction. The bidders don’t see the other bids, but because there are more bids than there are bonds available, financial institutions will bid the highest prices they can to avoid being shut out altogether. (FRB usually gets bids for 2 to 3 times as many bonds as they have available to sell.) This is good for UST, with a heavy emphasis on the “us”! High bond prices translate into low interest rate loans for UST.

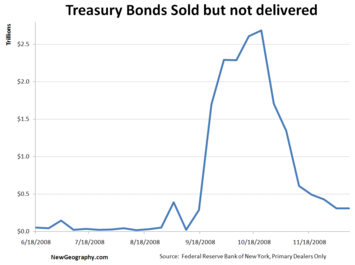

Bonds are funny that way: when a bond’s price goes up, its interest rate goes down, and interest is the cost of borrowing money. So we should like to see Treasury bonds selling at very high prices, and with very low costs to the UST. Unfortunately, all those fails-to-deliver — those phantom bonds — especially over the past few months, had the effect of pushing down the price of bonds by (artificially) increasing the supply. That was keeping the interest rate paid by UST higher than it needed to be over the last year or so.

When bond prices are high — or inching up, as they are now — we all benefit. UST sold $32 billion in 30-day Treasury bills on December 9th at a yield of 0%, meaning that investors are lending UST money for nothing except the promise to return their money without losing any of it. Investors bid for four times as many of these particular Treasury bills as were available for sale. This is as it should be.

As the primary brokers rush to cover their phantoms — those failed to deliver Treasuries of the past — in order to settle their transactions, we’re seeing a surge in the price of treasury securities. The prices of bonds are rising, the yield is falling; the UST is paying lower rates on the money it borrows from investors.

An increase in the price of the new bonds can also mean that the price of existing bonds - those already outstanding - will also increase. The increase in the prices of outstanding bonds will help my friend in New York. A good part of her $1 million retirement portfolio is invested in Treasuries. Treasury bond funds, like Merrill Lynch and Vanguard, are earning 11 to 12 percent for their investors.

These high rates of return in Treasury bond funds won’t last forever, of course. The number of fails-to-deliver in Treasuries is falling quickly, now that the spotlight is on. When settlement is final and on time, then the usual rules of supply and demand will apply. Prices of new bonds and those bonds in the funds (the outstanding bonds) will even out. But the demand for UST bonds will likely stay strong as long as there is global financial turmoil. And that demand turns out to be good for the US (lower interest rates) and good for us (higher prices for the bonds in funds).

These high rates of return in Treasury bond funds won’t last forever, of course. The number of fails-to-deliver in Treasuries is falling quickly, now that the spotlight is on. When settlement is final and on time, then the usual rules of supply and demand will apply. Prices of new bonds and those bonds in the funds (the outstanding bonds) will even out. But the demand for UST bonds will likely stay strong as long as there is global financial turmoil. And that demand turns out to be good for the US (lower interest rates) and good for us (higher prices for the bonds in funds).

People like my friend in New York ask me if Treasury bonds are safe. I tell them: if the US Treasury fails to pay you back, you’ll have bigger problems than a decrease in the value of your portfolio.

Susanne Trimbath, Ph.D. is CEO and Chief Economist of STP Advisory Services. Her training in finance and economics began with editing briefing documents for the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. She worked in operations at depository trust and clearing corporations in San Francisco and New York, including Depository Trust Company, a subsidiary of DTCC; formerly, she was a Senior Research Economist studying capital markets at the Milken Institute. Her PhD in economics is from New York University. In addition to teaching economics and finance at New York University and University of Southern California (Marshall School of Business), Trimbath is co-author of Beyond Junk Bonds: Expanding High Yield Markets.

Europe and even of Japan by

Europe and even of Japan by planners and politicians who travel abroad, there has long been a desire to reshape American cities along the lines of foreign models.Top Alternative of Google AdSense

October 2009 Update

Thanks to everyone for keeping this thread active over nine months now! You can always get the most recent data from the New York Fed. The Fails are on Page 5 (last page) of their weekly report.

For the week ended October 7, 2009, failures to deliver (FTD) in Treasuries were $24.6 Billion, up $5.5 billion from the previous week. Primary dealers report “cumulative” fails. The usual way to understand this is that $24.6 billion in Treasury FTDs are an average of $3.5 billion failed to deliver for 7 straight days; or $24.6 billion failed to deliver for only 1 day. In any event, weekly average reported FTDs this year ($65.3 billion through Oct 7) are still 50 percent higher than they were in 2007 ($42.3 billion, in the same period).

The “Treasury Market Practices Group” (set up under Geithner at FRB-NY) is a waste of good oxygen. No matter what they say they did about this problem, the fact is that it has not been fixed.

Even bigger fail to deliver numbers now are showing up in Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). As of Sept 30, there were $236 billion failed; Oct 7 it’s down to about $100 billion. I wrote a paper on settlement failures in bond markets which you can download for free. At the peak in 2004, some 40% of trades in MBS failed to settle.

Follow me on Twitter: SusanneTrimbath

Thanks for clearing this

Thanks for clearing this out, there are still people that don't really know what surety bonds are really about. For those of you who need further clarifications on the matter just click here.

I agree that in these time

I agree that in these time of recession, the value of bonds have gone down considerably but things are improving. Performance bonds are regaining their lost value which is good for organizations and traders.

Bank of America.....

Bank of America CEO Ken Lewis has been canned from the chairman position, but will remain CEO. Calls for Lewis to resign in shame and go cry alone with his money have been getting louder over the past few months. Ken Lewis is keeping his job, well, more or less. Ken Lewis will no longer have his position as Chairman of the Board of Bank of America. Granted, this doesn't mean he'll worry about cash advances ever again; he's still CEO of Bank of America. He had come under fire from shareholders and the general public, largely from the acquisition of Merrill Lynch last year which left B of A holding the bag absorbing billions in Merrill Lynch's bad debt. Despite the controversy, the shareholder's meeting involved board elections, and not a single board member was ousted. Bank of America still got billions in installment loans from the government, under the stewardship of Ken Lewis.

Phantom is correct!!

All these crooks are leading to the home market crashing. THere's no end to lower home prices. AT our current rate we should see pre 2000 home prices very soon!

Sources: http://www.homepricetrend.com

Re: Phantom is Correct

Take a look at this article from the Village Voice: http://www.villagevoice.com/2008-11-05/news/wall-streetwalkers-the-sleaz...

According to author Graham Rayman, Lehman wrote the mortgage, sold the bond and bought the credit default swap. They are refusing to take mortgage payments from homeowners, likely because the default swap is worth more than the mortgage regardless of the home price. They'll push up foreclosure inventory, pushing down prices, especially in OH, FL and NY where Lehman was most active.

Thanks for the homeprice link. I see that my new home town of Omaha is seeing price increases, decreased inventory and more sales. Looks like prices bottomed-out in October 2008 for us.