During a tour to Paris, Bruce Springsteen explained that his dream was for the US to adapt a Swedish style welfare state. The famous musician is far from alone in idealizing Nordic policies. The four Nordic nations (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) are often regarded as prime role-models the policies to be emulated by others. Internationally, advocates of left of centre policies view these countries as examples of how high tax social democratic systems are viable and successful. Paul Krugman, for example, has said: “Every time I read someone talking about the ‘collapsing welfare states of Europe’, I have this urge to take that person on a forced walking tour of Stockholm”.

This admiration has a long history. In the mid-1970s Time Magazine described a country that sounded much like a utopia. “It is a country whose very name has become a synonym for a materialist paradise”, the international magazine wrote and continued to report about Sweden: “No slums disfigure their cities, their air and water are largely pollution free... Neither ill‑health, unemployment nor old age pose the terror of financial hardship.” Similarly, political scientist John Logue argued in 1979: “A simple visual comparison of Scandinavian towns with American equivalents provides strong evidence that reasonably efficient welfare measures can abolish poverty as it was known in the past; economic growth alone, as the American case indicates, does not”. Logue believed that the greatest threat to the Nordic welfare states was that they were too successful; eliminating social problems to such a degree that people forgot the importance of welfare policies.

The high regard comes as no surprise. Nordic societies are uniquely successful. Not only are they characterised by high living standards, but also by other attractive features such as low crime rates, long life expectancy, high degrees of social cohesion and even income distributions. Various international rankings conclude that they are amongst the best, if not the best, places in the world in which to live. One example is the “Better Life Index”, complied by the OECD. In the 2014 edition of the index Norway was ranked as the nation with the second highest level of well-being in the world, followed by Sweden and Denmark in third and fourth position. Finland ranked as the eighth best country.

The OECD “Better Life Index”

|

1. Australia |

|

2. Norway |

|

3. Sweden |

|

4. Denmark |

|

5. Canada |

|

6. Switzerland |

|

7. United States |

|

8. Finland |

|

9. Netherlands |

|

10. New Zealand |

If one disregards the importance of thinking carefully about causality, the argument for adopting a Nordic style economic policy in other nations seems obvious. The Nordic nations – in particular Sweden, which is most often used as an international role‑model – have large welfare states and are successful in a broad array of sectors. This is often seen as proof that a ”third way” policy between socialism and capitalism works well, and that other societies can reach the same favourable social outcomes simply by expanding the size of government. If one studies Nordic history and society in‑depth, however, it quickly becomes evident that the simplistic analysis is flawed.

To understand the Nordic experience one must bear in mind that the large welfare state is not the only thing that sets these countries apart from the rest of the world. The countries also have homogenous populations with non-governmental social institutions that are uniquely adapted to the modern world. High levels of trust, strong work ethic, civic participation, social cohesion, individual responsibility and family values are long-standing features of Nordic society that pre-date the welfare state. These deeper social institutions explain why Sweden, Denmark and Norway could so quickly grow from impoverished nations to wealthy ones as industrialisation and the market economy were introduced in the late 19th century. They also play an important role in Finland’s growing prosperity after the Second World War.

Take Sweden as an example. In 1870 free markets were introduced in this agrarian society. During the coming 100 years Sweden combined low taxes, liberal regulations and strong working ethics to experience an unrivalled growth rate in Europe. In 1870 Sweden’s GDP per capita was 57 per cent lower than in the UK. In 1970 it had risen to become 21 per cent higher. The shift towards high taxes and state involvement actually began occurred around 1970, resulting in a long-lasting period of stagnation that was broken through ambitious market reforms during the 1990s and onward.

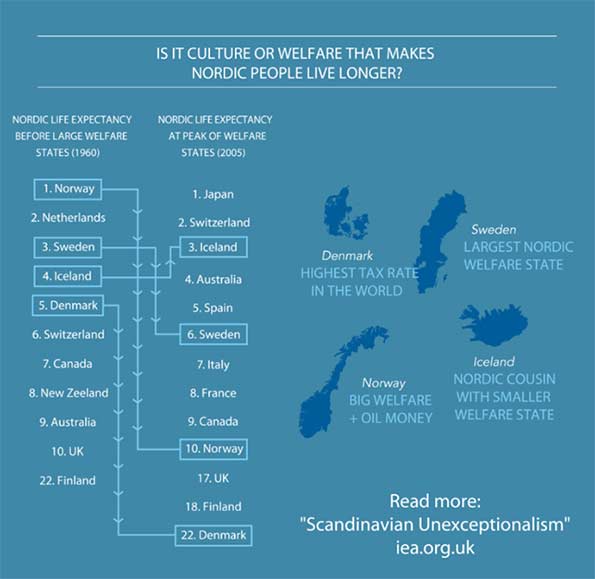

Perhaps even more interestingly, even the social progress that Nordic countries are admired for developed during the latter part of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, developed not under socialism but at a time when Nordic countries combined free markets and low taxes with small (and efficient) welfare states. Researchers have for example shown that it was during this period that Sweden and Denmark developed a relatively equal income distribution. Long life expectancy is another example. In the picture below I show the life expectation at birth is shown for various OECD nations in 1960 – when Nordic nations had small welfare states – and 2005 – when Nordic welfare states were at their peak. In both periods Nordic countries were characterized by relatively long life expectancy, but if anything, this was more the case when the countries had small rather than large welfare states. The reason is simply that everything is not politics, cultural attributes such as a love for nature and healthy diets explains much of Nordic citizens good health.

Similarly, it comes as no surprise that descendants of the Nordics who migrated to the US in the 19th century are still characterised by favourable social outcomes, such as a low poverty rate and high incomes. In fact, as shown below, Nordic Americans have considerably higher living standard in capitalist America than their cousins in the Nordics. This is interesting, since those Nordic citizens who migrated to the United States in large groups during the 19th and 20th centuries were anything but an elite group. Rather, it was often the poor who left for the opportunities on the other side of the Atlantic.

A key lesson from the success of Nordic society lies in what can broadly be defined as “culture matters”. We should not be surprised that it is these nations, with their historically strong work ethic and community-based social institutions, t have had fewer adverse effects from their welfare states and are therefore used as the poster child for those wishing to extol the benefits of active welfare policies. On the other hand, Southern European countries with similar sized welfare states and size of government have had less favourable outcomes.

Paul Krugman is right in noting that a forced walking tour of Stockholm disproves the idea of the collapsing welfare states of Europe. Nordic societies have not collapsed under the weight of welfare policies, particularly since they have lately adopted by introducing market reforms, reducing the generosity of welfare programs and cutting taxes. Such a tour may perhaps also be wise for Krugman himself, in teaching that Scandinavian countries have been rather unexceptional. The normal economic rules apply: incentives, economic freedom, a strong self-sufficient culture and a regime of good governance all matter when it comes to economic success. The question that remains is whether Scandinavian countries will continue their return to the free-market roots that have historically served them so well. If so, the Nordic culture of success can in combination with sound policies allow growth, innovation and entrepreneurship to flourish.

Dr. Nima Sanandaji is a research fellow at CPS, and the author of “Scandinavian Unexceptionalism - Culture, Markets and the Failure of Third-Way Socialism”. The book, which was recently released is currently being translated to a number of different languages. The entire book is available through the Institute of Economic Affairs which has published it.