As I am writing this article, South Africa is predicted, following the coronavirus crises, to have an unemployment rate of 50% i.e. 1 in 2 working adults .The country’s lockdown has now been longer than the one in authoritarian China and to make matters worse, South Africa’s credit rating has been recently downgraded by agencies such as Fitch, Standard and Poor, and Moody’s.

South Africa can’t service its debts and its finance minister has already started talks with the IMF for a bailout. Although the roots of the crisis are long in the making, the ANC government will blame the fiscal crises on the coronavirus. The long lockdown has done little to stop the high homicide rate and a pattern of gender violence and rape that annually out competes Latin America.

The ANC government, itself a movement born out of anti-colonial and pro-Soviet style propaganda seems incapable of addressing the needs of destitute South African youth. The opportunities for upward mobility out of a working-class family seems slim. Young South Africans are now in the majority of the population. The average age in the country is 26.5 years old, but just over half are unemployed, not including those that have given up looking for work. The majority of young South Africans, including many college graduates, may never work in their lives, according to projections from the Institute of Race Relations.

The emerging generation is not prepared for the future. An estimated 8 out of ten 10 year old kids cannot read for meaning and 60% of all newborn babies do not have the information of their father on their birth certificate. South Africa has lots of available work and a large skills gap, but the unemployment problem is unfortunately an unemployability problem. PCWs Survey of 1300s CEOs cite this disparity as the reason why they cannot hire newly skilled recruits for the technologically available jobs.

The readmission of the country to the world economy in the 90s inadvertently destroyed the competitiveness of many institutions like the parastatals. There are about 700 of these state ran corporations in existence such as the national power utility, weapons manufacturer, national airline, and telecoms provider. These corporations are meant to run at profit, or they are subsidized by the government to perform public works. They originated as part of the South African version of the New Deal that were initially set up with the aim aimed at solving white Afrikaner poverty, but during Apartheid, their scopes were expanded to develop South Africa’s local based industries so that they economy whether the damaged caused by international sanctions.

With the dawn of a democratic South Africa, these parastatals could have helped many black South Africans get into the middle class, but unfortunately in the last 30 years they have been managed into the ground. The Auditor General’s report last year cast a serious doubt on their feasibility as the government constantly kept on bailing them out. The government itself is also in trouble as the public sector has become ever more bloated, with salaries now eating one third of the national budget. We are now at a high debt fiscal cliff coupled with high unemployment.

The most prominent example is that power utility Eskom that on the eve of Nelson Mandela’s election provided South Africa cheapest electricity in the World, selling its surplus electric to other African countries. Now we have higher energy prices, and unserviceable debts coupled with rolling black outs. The minimum wage and increasingly difficult labor laws is making it increasingly difficult to hire unskilled labourers in a country with excess supply. South Africa is also facing a water crisis as Cape Town, in 2018, was on the brink of being the first industrial city to ran out of Water. The crisis has predictably been linked to climate change, but government corruption, bad planning and simple incompetence played a commanding role. This corruption and incompetence has led many young South African graduates such as myself to immigrate to other countries in the last two decades.

In the last two decades since the end of Apartheid South Africa saw the growth of a black Oligarchy through its policies of affirmative action and black economic empowerment, but it has not solved widespread inequality and poverty. Inequality has also increase between certain communities of the white population as white poor Afrikaner townships began establishing themselves around Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Beneath their often provocative, post-colonial rhetoric, these are not selfless revolutionaries. President Cyril Ramaphosa is one of the wealthy elite, his brother in law Patrice Motsepe, a profiteer of South Africa’s mines, sits atop the pyramid as the richest. Both made their money on lucrative Black Economic Empowerment deals – a form of legalized rent seeking that was meant to address the legacies of Apartheid by transferring equity to black South Africans. The President’s other brother in law, Jeff Radebe, is the minister of Energy.

I have been living in Paris since 2015 and I am constantly stunned by the level of ignorance that the Western World have of past and present South Africa. The word Apartheid itself is in danger of losing its meaning in ways that dishonor those that fought against it.

South Africa’s post-Apartheid experience was supposed to be different from those of other post-colonial state and initially was, especially in the early 90s and 2000s. Yet as in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Angola, and Tanzania , we have devolved into a country led by classic African Oligarchs who serve themselves and care nothing for their own people.

Many Western Media outlets are still stuck on the honeymoon period of the Rainbow Nation. There is a naïve optimism about how racism automatically disappeared in the 30 years after Nelson Mandela was elected President. Apartheid was a dehumanizing policy, first to the black Africans but also to those of us, like my father, who were called up to preserve the segregated state, and emerged scared from it.

Sadly, the legacies of the apartheid have not disappeared, and have contributed to modern South Africa’s inequality. Bantu Education was created largely to train black people for manual jobs. This has left many black South Africans with parents who do not know how to help them move to higher education levels.

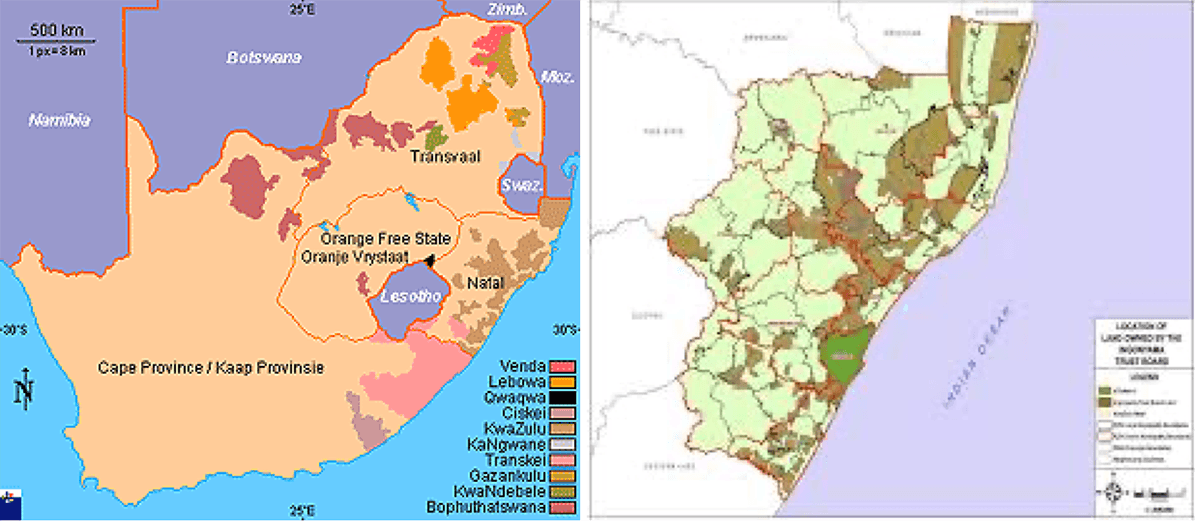

In terms of Town Planning, Apartheid was enforced through the policy of separate development a social policy that prohibited non-white South Africans from owning land. The infamous 1913 land act relegated most black South Africans to just over 13% of the country’s land, but that was only the beginning. As time went on these black reservations would double in size and be called homelands. Black people would later be stripped of their land in the homelands and it would be handed to the tribal chiefs. The few areas inside of the “white South Africa” that black people could still owned land on were known as ‘black spots’. As Apartheid laws got tighter, they were systematically dismantled, and the communities were supposed to be resettled either to the homelands or to neglected locations around the cities. This is roughly how the process of systematic and political and economic disenfranchisement unfolded during the last century.

Apartheid was enforced in different levels of government and in an arbitrary manor that many were implemented led to the inherent contradictions of the system. The inner cities and suburbs of cities such as Pretoria, Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town, were restricted to white South Africans in what was called the Group Areas act and around these cities the government established areas known as Townships for the black workers. Initially they were settled as locations for the mine workers to live on and there is still some remnant of the old miner hostels in some townships.

The black workers would supply the white areas in complex labour arrangement that allowed them to only work as unskilled labourers in occupations such as gardeners, domestic workers, on the construction sites and the country’s mines. The system perpetuated the master and servant relationship and to a large extend today the poor black working class serves the new South African elite. This elite is no longer all white; most homes in the country are now owned by non-whites. More black students now graduating each year from university than white students.

The area photo below shows the township area adjacent to a white suburb.

Remarkably, thirty years after the collapse of apartheid, the old patterns continue to apply to most South Africans. Black South Africans in the Township were never given ownership for the land but were made citizens of black homelands run by tribal chiefs. The Homelands area, also known as Bantustans were supposed, under Apartheid ideology, to develop and eventually become attractive to the black workers, but they failed to create opportunities for their residents, many of whom fled to the previously white-controlled cities. These remain largely feudal structures; the Zulu King’s Ingonyama Trust is the country’s largest landowner in modern South Africa. He owns almost 30% of the land in the Province of Kwazulu Natal. where almost 30% of the citizens are food deprived.

The figure below shows the area that were designated as Bantustans and Apartheid and on the Right-hand side the land that is currently owned by the Zulu Kingdom. They are identical.

Whether under the control of colonial administrators or white nationalists, this system remains nothing better than a modern form of Feudalism. The vast majority of people living in these lands do not have any legal tenure.

Instead they head to areas such as Cape Town, Johannesburg and Pretoria is seeing some of the highest levels of migration on the African Continent while the countryside is effectively ageing. Most of the migrants go to the Township area that were established around the once white-dominated and now elite-dominated cities.

The Township area can best be explained by Hernando de Soto’s concept of Dead Capital. The government of the day has failed to give title deeds to those that live in the homes while expanding social housing known in a scheme known as RDP houses. The scheme provides South Africans with a free house, where they have an ownership, but no tradable title. This means that they cannot get a loan to finance a business or leave an inheritance to their children.

The basic reality is that the current South African government has, in albeit less racially exclusive way, reinforced the feudal patterns that existed under the British and Afrikaner nationalist regime. One positive sign: The Free Market Foundation has started a private Charity that takes donations of the public to try and get the some of the between five and seven million homes built by the apartheid government homes registered with own title.

The importance of access to land ownership has been a key factor as a means for upward mobility In the West, as well as in Japan and parts of East Asia, for generations. Until ordinary South Africans can gain access to land, as well as quality education, the promise of a better, more just nation will simple remain an empty one.

Bibliography

- ASH, JEFF WICKS AND PAUL. 'It's going to have a devastating effect': Jobs axe hangs over half of SA's workforce. Sunday Times. [Online] May 03, 2020. [Cited: 06 2020, 15.] https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/news/2020-05-03-its-going-to-ha....

- Africa Check. FACTSHEET: South Africa’s crime statistics for 2018/19. Africa Check. [Online] September 12, 2019. [Cited: 06 2020, 16.] https://africacheck.org/factsheets/factsheet-south-africas-crime-statist....

- Sarah Howie, Celeste Combrinck, Karen Roux, Mishack Tshele, Gabriel Mokoena, Nelladee McLeod Palane. PROGRESS IN INTERNATIONAL LITERACY South African Children’s Reading Literacy Achievement. s.l. : University of Pretoria Centre for Evaluation and Assessment, 2016.

- Johan Fourie, Stellenbosch University. News24. Why are there so many single mothers? [Online] September 26, 2018. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://www.news24.com/fin24/finweek/opinion/why-are-there-so-many-singl....

- South Africa has asked for a loan from the IMF. South Africa has asked for a loan from the IMF. BusinessTech. [Online] June 8, 2020. [Cited: 06 2020, 16.] https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/405685/south-africa-has-asked....

- PWC. 22nd Global CEO Survey Skills gap is hampering businesses’ recruitment efforts – PwC report. 2019.

- Africa, Statistics South. Quarterly Labour Force Survey. Pretoria : STATS SA, Q1 2019.

- Cronje, Franse. Free Market Foundation. FMF NEWSLETTER 26 September 2018. [Online] Free Market Foundation, September 26, 2018. [Cited: 06 2020, 16.] https://www.freemarketfoundation.com/article-view/fmf-newsletter-26-sept....

- businesstech. Auditor General casts doubt on the future of South Africa’s state-owned entities. [Online] November 20, 2019. [Cited: 06 2020, 16.] https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/355745/auditor-general-casts-....

- Alexander Winning, Olivia Kumwenda-Mtambo, Wendell Roelf and Mfuneko Toyana. Reuters. EXPLAINER-Why South Africa's public wage bill is a problem. [Online] February 2020, 27. [Cited: 06 18, 2020.] https://www.reuters.com/article/safrica-economy-wages/explainer-why-sout....

- Writer, Staff. businesstech. Eskom from apartheid to the ANC. [Online] March 19, 2020. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://businesstech.co.za/news/trending/82841/eskom-from-apartheid-to-t....

- Olivier, David W. The Conversation. Cape Town’s water crisis: driven by politics more than drought. [Online] 12 12, 2017. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://theconversation.com/cape-towns-water-crisis-driven-by-politics-m....

- Africa Check. BusinessTech. South Africa’s emigration problem – no one knows how big the brain drain really is. [Online] May 2019, 23. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://businesstech.co.za/news/lifestyle/318736/south-africas-emigratio....

- The Green Dam. SABC Special Assignment, JourneymanTV, 2006.

- MABUZA, ERNEST. TimesLive. Patrice Motsepe denies benefiting from brothers-in-law Ramaphosa and Radebe. [Online] February 18, 2019. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://www.timeslive.co.za/politics/2019-02-18-patrice-motsepe-denies-b....

- Schussler, Mike. Businesstech. The truth about land and home ownership in South Africa. [Online] 06 18, 2020. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://businesstech.co.za/news/wealth/113714/the-truth-about-land-and-h....

- Reporter, Staff. Mail and Guardian. Black graduate numbers are up. [Online] 02 18, 2020. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://mg.co.za/article/2016-05-17-black-graduate-numbers-are-up/.

- Robinson, Melia. businessinsider. A drone captured these shocking photos of inequality in South Africa. [Online] 10 2, 2016. [Cited: 06 16, 2020.] https://www.businessinsider.com/drone-photography-south-africa-2016-8?IR....

Hügo Krüger is a Structural Engineer with working experience in the Nuclear, Concrete and Oil and Gas Industry. He was born in Pretoria South Africa and moved to France in 2015. He holds a Bachelors Degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Pretoria and a Masters degree in Nuclear Structures from the École spéciale des travaux publics, du bâtiment et de l'industrie (ESTP Paris). He frequently contributes to the South African English blog Rational Standard and the Afrikaans Newspaper Rapport. He fluently speaks French, Germany, English and Afrikaans. His interests include politics, economics, public policy, history, languages, Krav Maga and Structural Engineering.

Lead photo credit: Kandukuru Nagarjun via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.