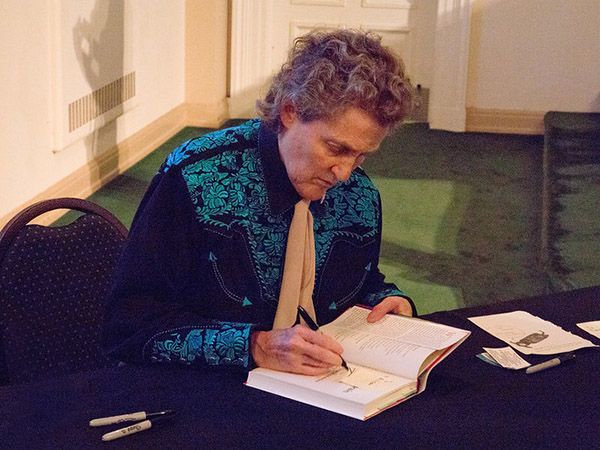

Many of you will be familiar with Temple Grandin. She’s the autistic woman who designs slaughterhouses from the cattle’s perspective. By organizing the process in a way that’s calming to the animals it improves efficiency. Her primary contribution is the recognition that animals are highly sensitive to small symbolic details: a shadow, a dangling chain, a hose left on the ground, a flapping flag. If the details are controlled the animals remain docile relative to the larger picture of what’s really happening at the abattoir.

Photo credit: Counse via flickr, CC 2.0 License.

People are subject to the same dynamics when choosing where and how to live. The obsession with symbolic details overwhelms the substance. Those little details become the driver of development patterns, municipal regulations, finance mechanisms, infrastructure investments, insurance parameters, and the social expectations that dominate private home owner associations. Individuals deviate from these norms at their peril. But the little details are fundamentally different from external reality.

I have a cousin in Southern California who was hit hard by the 2008 crash. Unemployment. Foreclosure. Nothing good. Like millions of other families she and her husband never recovered and have spent the last decade working an assortment of part time, low wage, no benefits jobs that keep them perpetually exhausted and demoralized without any improvement in their condition. They now live in a double wide mobile home in the desert along with my elderly aunt they look after.

They own the mobile home, but rent the land under it. Since they own the “improvement” on the property (the house) they’re obliged to pay property tax on it. They need to insure the home and they need to continuously make repairs they can’t actually afford on a structure that was poorly built to begin with. Meanwhile the house is rapidly depreciating like a used vehicle and has little or no resale value at this point. Any appreciation in the value of the land benefits their landlord, not them.

On top of this comes the gas and electric bills in a harsh climate (it’s been 108F / 42C this week) with no real insulation and substandard doors and windows. Plus this is the kind of location where multiple car ownership is mandatory so they have the usual collection of auto loans, car insurance, repairs, and gas to manage. And since this is America they’ve fallen in to the usual trap of earning slightly too much to qualify for government subsidized health insurance, but can’t possibly afford private care out of pocket. At the end of each month there’s nothing left. Basically, they’re in a very big boat with millions of other people – and it’s sinking.

For the last ten years we’ve been having an extended conversation. I have a tiny bit more resources than my cousin and I’ve repeatedly suggested a mutually beneficial collaboration. I’d like a modest property somewhere outside my home territory of San Francisco to fall back on in case of earthquake, fire, economic distress… whatever. (It’s not like we could ever have a global pandemic or anything.)

This proposed property might serve as an occasional holiday retreat or ultimately a retirement home. But I’d like it to be as close to mortgage free as possible so that means somewhere out of state where property is radically less expensive. What I would really need in this scenario is a caretaker to occupy the place and I was hoping my cousin and her husband would accept that role – rent free. We could solve each other’s problems if we teamed up.

Over the years we traveled to various states together and poked around. From the beginning things were complicated. My cousin’s husband is proud. He doesn’t want “assistance.” He wants to own his own damn home. What he really needs is a solid job and a higher income not a “collaboration” with a weird in-law. (And yes, I’m hyper aware of my many flaws.) He’s not interested in a caretaker position. He says he’d be happy with a simple and affordable property, but every location he expresses interest in is every bit as expensive as California. We’d all enjoy a boutique town in the mountains, but that’s just not in the cards.

My cousin is equally fierce in her demand for independence. She’ll never allow herself to be under anyone’s thumb. She needs security that isn’t tied to a “partnership.” She insists on explicit control of her own life and home. And there’s the question of my aunt who needs to be accommodated.

I asked how a rent free situation with a blood relative is worse than their present circumstances at the mobile home park. It’s been a decade since their previous home was repossessed and they’re no where closer to anything better. They’re also ten years older than they were at the beginning of our conversation. My cousin is now 55 and her husband is 60. As the economy continues to implode they’re competing for jobs with an army of shiny young people fresh out of university.

They both have lifelong work experience in live performance and video, mostly in community theater. Covid-19 has created a second crisis for their household finances that looks to be worse than the 2008 crash. But at the moment they’re still entirely preoccupied with the small highly symbolic and emotionally charged details: a shadow, a dangling chain, a hose left on the ground, a flapping flag. I fear I know what comes next for them. Shrug.

This piece first appeared on Granola Shotgun.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He's a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.