Stanley Kurtz's new book, Spreading the Wealth: How Obama is Robbing the Suburbs to Pay for the Cities describes political forces closely tied to President Obama who have pursued an agenda to "destroy" the suburbs for many years. He expresses concern that a second Obama term will be marked by an intensification of efforts to destroy the suburbs through eviscerating their independence thought the imposition of "regionalism". The threat, however, long predates the Obama administration and has, at least in some cases, been supported by Republicans as well as by Democrats.

America is a suburban nation. Nearly three-quarters of the residents of major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population) live in suburbs, most in smaller local government jurisdictions. Further, outside the largest metropolitan areas most people live in suburbs, smaller towns or smaller local government jurisdictions.

Smart Growth

The anti-suburban agenda has more than one dimension. The best known is smart growth, known by a variety of labels, such as compact development, growth management, urban consolidation, etc. Smart growth, from our research, also is associated with higher housing prices, a lower standard of living, greater traffic congestion and health threats from more intense local air pollution.

Regionalism

Another, less well-known anti-suburban strategy is regionalism, to which Kurtz grants considerable attention. Regionalism includes two principal strains, local government amalgamation and metropolitan tax sharing. Both of these strategies are aimed at transferring tax funding from suburban local governments to larger core area governments.

Social welfare and differing income levels are not an issue at this level of government. Local governments, cities, towns, villages, boroughs and townships, finance local services principally with their own local taxes. The programs aimed at social welfare or providing income support are generally administered and financed at the federal, state or regional (county) level. Any suggestion that local suburban jurisdictions are subsidized by core local governments simply reveals a basic unfamiliarity with US municipal finance.

Local Government Amalgamation

Opponents of the suburbs have long favored amalgamating local governments (such as cities, towns, villages, boroughs and townships). There are two principal justifications. One suggests "economies of scale" --- the idea that larger local government jurisdictions are more efficient than smaller governments, and that, as a result, taxpayers will save. The second justification infers that a larger tax base, including former suburbs, will make additional money available to former core cities, which are routinely characterized as having insufficient revenues to pay for their services. Both rationales are without foundation.

Proponents of amalgamation incessantly refer to the large number of local governments in some states, implying that this is less efficient. The late Elinor Ostrum put that illusion to rest in her acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in economics in 2009:

Scholars criticized the number of government agencies rather than trying to understand why created and how they performed. Maps showing many governments in a metropolitan area were used as evidence for the need to consolidate.

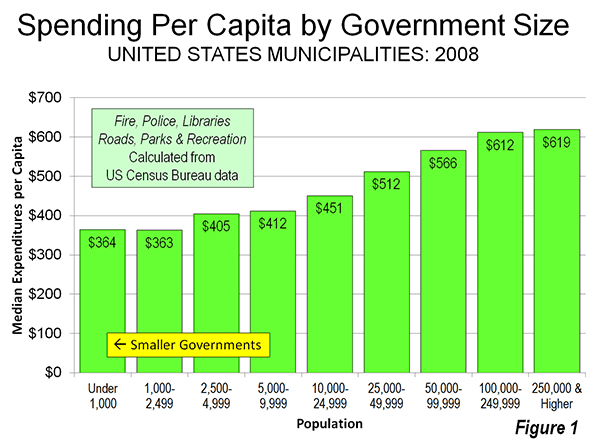

The reality is that there is a single measure of efficiency: spending per capita. Here there is a strong relationship between smaller local government units and lower taxes and spending. Our review of local government finances in four states (Pennsylvania, New York, Indiana and Illinois) indicates that larger local governments tend to be less efficient, not more. Moreover, the same smaller is more efficient dynamic is evident in both metropolitan areas as well as outside. "Smaller is better" is also evident at the national level (Figure 1).

Yet the "bigger is better" faith in local government amalgamation remains compelling to many from both the Right and Left. Proponents claim that smaller local governments are obsolete, characterizing them as being from the horse-and-buggy era. The same logic could be used to eliminate county and even state governments. However, democracy remains a timeless value. If people lose control of their governments to special interests (which rarely, if ever, lobby for less spending), then democracy is lost, though the word will still be invoked.

Support of local government amalgamation arises from a misunderstanding of economics, politics and incentives (or perhaps worse, contempt for citizen control). When two jurisdictions merge, everything is leveled up, from labor costs to service levels. The labor contracts, for example, will reflect the wage, benefit and time off characteristics of the more expensive community, as the Toronto "megacity" learned to its detriment.

Further, special interests have more power in larger jurisdictions, not least because they are needed to finance the election campaigns of elected officials, who always want to win the next election. They are also far more able to attend meetings – sending paid representatives – than local groups. This is particularly true the larger the metropolitan area covered, since meeting are usually held in the core of urban area not in areas further on the periphery. This greater influence to organized and well-funded special interests – such as big real estate developers, environmental groups, public employee unions – and drains the influence of the local grassroots. The result is that voters have less influence and that they can lose financial control of larger local governments. The only economies of scale in larger local government benefit lobbyists and special interests, not taxpayers or residents.

Regional Tax Sharing

Usually stymied by the electorate in their attempts to amalgamate local governments, regional proponents often make municipal tax sharing a priority. The idea is that suburban jurisdictions should send some of their tax money to the core jurisdictions to make up for the claimed financial shortages of older cities. Yet this ignores the fact, as Figure 1 indicates, that larger jurisdictions generally spend more per capita already and generally tax more, as our state reports cited above indicate. Larger jurisdictions also tend to receive more in state and federal aid per capita. A principal reason is that the labor costs tend to be materially higher in larger jurisdictions. In addition to paying well above market employee compensation, many larger jurisdictions have burdened themselves with pension liabilities and post employment health benefits that are well above what their constituencies can afford. The regionalist solution is not to bring core government costs in line with suburban levels but force the periphery to help subsidize their out of control costs.

Howard Husock, of Harvard University's JFK School of Government (now at the Manhattan Institute) and I were asked to evaluate a tax sharing a plan put forward by former Albuquerque mayor David Rusk for Kalamazoo County, Michigan (The Kalamazoo Compact) more than a decade ago. Our report (Keeping Kalamazoo Competitive)found no justification for the suburban areas and townships of Kalamazoo County to share their tax bases with the core city of Kalamazoo. The city already spent substantially more per capita, received more state aid per capita and had failed to take advantage of opportunities to improve its efficiency (that is, lower the costs of service without reducing services). We concluded that the "struggling" core city had a spending problem, not a revenue problem. To the credit of the electorate of Kalamazoo County, the tax sharing proposal is gathering dust, having been made impractical by suburban resistance.

Spreading the Financial Irresponsibility

The wanton spending that has gotten many larger core jurisdictions into trouble should not have occurred. The core cities are often struggling because their political leadership has "given away the store," behavior that does not warrant rewarding. Elected officials in the larger jurisdictions had no business, for example, allowing labor costs to become higher than necessary or granting rich pension benefits paid for by private sector employees (taxpayers), most of whom enjoy only much more modest pension programs, if at all (See note below).

The voters are no match for the spending interests with more efficient access to City Hall. The incentives in such larger jurisdictions are skewed against fiscal responsibility and the interests of taxpayers. Making an even larger pool of tax revenues available can only make things worse.

At the same time, the smaller, suburban jurisdictions around the nation are often the bright spot in an environment of excessive federal, state and larger municipal government spending. Their governments, close to the people, are the only defense against the kind of beggar-the-kids-future spending that has already captured the federal government, state governments and some larger local jurisdictions.

Either Way the Threat is Very Real

Even if President Obama is not re-elected or if a second Obama Administration does not pursue the anti-suburban agenda, the threat to the suburbs will remain very real. This is not just about the suburbs, and it is certainly not some secret conspiracy. What opposing regionalism means is the preservation of what is often the last vestige of fiscal responsibility. It is not that the elected officials in smaller jurisdictions are better or that the electorate is better. The superior performance stems from the reality that smaller governments are closer to the people, and decision-making tends more to reflect their interests more faithfully than in a larger jurisdictions.

Ed. note: This piece was corrected to add quotation marks around the word "destroy" in the first paragraph. That clause is included in reference to Kurtz's characterization, not the author's.

------

Note: A report by the Pew Charitable Trusts (Promises with a Price) indicated that "... in general, the private sector never offered the level of benefits that have been traditionally available in the public sector." The report further indicated that 90 percent of state and local government retirees are covered by the more expensive defined benefit pension programs, compared to 20 percent in the private sector. The median annual pension in the state and local government sector was cited at 130 percent higher than in the private sector. While 82 percent of state and local government retirees are covered by post-employment medical benefits, the figure is 33 percent in the private sector. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, after accounting for the one-third higher wages per hour worked among state and local government workers, employer contribution to retirement and savings is 160 percent higher than in the private sector (March 2012). A just published Pew Center on the States report (The Widening Gap Update) indicates that states are $1.3 trillion short of the funding required to pay the pension and post employment medical benefits of employees. This does not include programs administered by local governments.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Lead Photo: Damascus City Hall (Portland, Oregon metropolitan area) by Wiki Commons user Tedder.

True, but

Lyle I can't disagree with you: there is lots of land not "naturally in a metro region dominated by a large city" in much of the midwest and great plains. But if few live on that land it doesn't quite matter so much. Even in Iowa - for example - that majority of its population already live in Metropolitan areas. And an even larger share of the state's economic production value occur in these Metropolitan areas. As for where to stop the dependency on a "large city": that's sort of what Metropolitan Statistical Area definitions are all about.

It's in the state's best interest - or any similar state - to do everything it can to nurture and support these growing metro regions. This is not a novel trend. The population and geography of economic activity throughout the Midwest and Great Plains has been rapidly urbanizing for years. Another case for more regional - rather than local - control over public services like land use regulation (among other things) and the distribution of capital expenditures on important regional amenities and infrastructure. If the rapidly urbanizing Midwestern states don't start a culture of internal cooperation; their performance will reflect that.

Even in flyover Iowa, there are strong and damaging local conflicts between local governments in Des Moines (with fewer than 600,000 people, a small metropolitan region by comparison to many).

The children just can't play nicely and see the writing on the wall. To compete with the better-established, larger, and in many cases more prestigious regions; these places need to offer more than a cost advantage. Well, if they're to be successful in the long-term anyways.

fraser centerpoint

Twin Fountains

design & build by fraser centerpoint