The New York Times ran an article recently that’s nominally about football, but really gives insight into the decline of the Midwest and the rise of the South. Called “As Big Ten Declines, Homegrown Talent Flees,” this piece ties in perfectly with my recent essay on the differing social states of the Midwest and South. The NYT’s money quote says it all:

The SEC sold excellence. The Big Ten sold tradition.

Ironically, it is the formerly stigmatized “backwoods” South that has embraced excellence while the former industrial champion of the Midwest has spurned it. I don’t think that Midwesterners understand how much things have changed in the South. I hear the same stereotypical view of the South that might have had a lot of truth decades ago but have changes substantially. For example, those who think it is both a good thing and bad have quipped that Indiana is like an extension of the South into the Midwest. I don’t think so.

For example, Charlotte built a light rail system. Dallas has poured a billion dollars into a downtown arts district. Atlanta has a multi-billion infill strategy around its former Belt Line railroad. Nashville eliminated downtown parking minimums and implemented a form based code. South Carolina has its German style apprenticeship program. North Carolina built Research Triangle Park – in 1959. Southern cities like Atlanta have proudly claimed and built success around their black heritage. And Charlotte’s Chamber of Commerce CEO said, “To understand Charlotte, you have to understand our ambition. We have a serious chip on our shoulder. We don’t want to be No. 2 to anybody.” Outside of Chicago, does anybody in the Midwest talk like that?

Sure, there are bits and pieces here and there in the Midwest that speak to excellence. But they are the anomalies in a region that has retrogressed. Whereas in the South they’ve massively elevated their game in the last 40 years and are working hard to keep getting better. Sure, low costs and taxes play a role in their success. Climate and the universality of air conditioning as well. But they aren’t content to rest on just that. They want to get better. Meanwhile the Midwest is regressing towards what the South used to be such as, for example, by turning paved roads back to gravel because they can’t afford the maintenance.

The NYT piece brings up an interesting factor driving the rise of the SEC vs. the Big Ten, namely the shift in underlying population ratios over time: “An instructive comparison is Michigan and Georgia. In 1960, Michigan had twice Georgia’s population; in 1990, it was nearly one and a half times as big; today, their populations are roughly equivalent.”

The decline in Midwest population and economic heft brings with it a price that has to be paid. It’s showing up in the football world today. But it’s sure to hit the academic prowess of the Midwest’s major state schools as well. How long can these places maintain their relative rankings of excellence without the financial firepower to play in the big leagues? There’s more inertia on the academic side, but don’t think it won’t eventually happen here as well. The same is true in many other aspects of civic life. Even mighty Chicago has nearly bankrupted itself in its efforts to keep up with other global cities.

The Big Ten obviously saw the writing on the wall and decided to expand outside the region. I dislike this for reasons of, naturally, tradition. But it’s a rational response to a declining marketplace. Similarly, the Cleveland Orchestra established a Miami residency in the pursuit of cash to keep its artistic excellence intact. Might some of these institutions at some point become Midwest in name only? Time will tell.

Not everyone agrees with the idea that the SEC vs. Big 10 comparison is a relavent proxy, basically saying that it’s ludicrous to say that football proves anything. I don’t think that it does. But I will make three points:

1. The differing fortunes of the two conference is yet another in an extremely long series of data points and episodes that demonstrate a shift in demographic, economic, and cultural vitality to the South.

2. Sports is one of the many areas in which Midwestern states have clung to traditional approaches, even though those approaches haven’t been producing results.

3. Demographic and economic changes have consequences. It’s not realistic to expect that the Midwest’s excellent institutions will necessarily be able to retain excellence when supported by hollowed out economies.

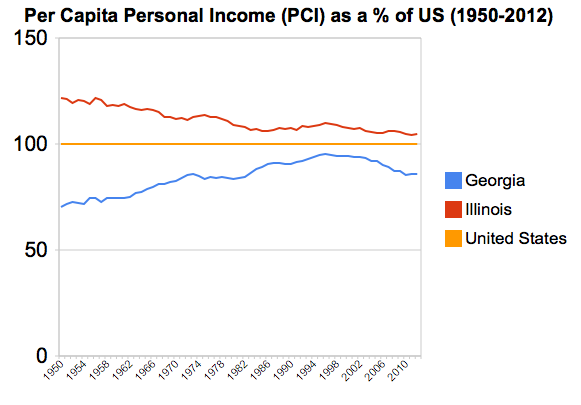

I’d like to throw up a couple of charts to illustrate the longer term trends at work. The first is a comparison of per capita personal income as a percent of the US average for Illinois vs. Georgia since 1950:

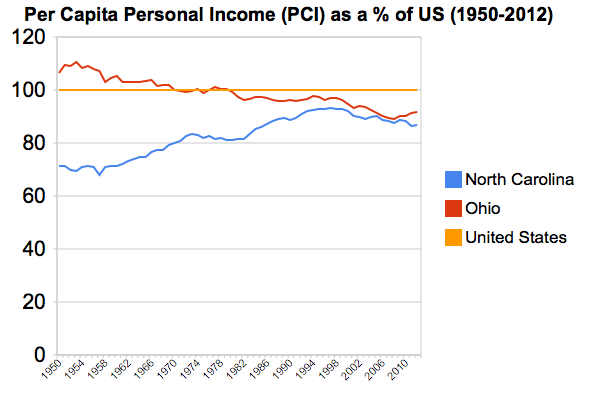

Here’s the same chart of Ohio vs. North Carolina:

If I put up the population or job numbers, the same charts would show the South mutilating the Midwest. (Indiana, Georgia, and North Carolina were all about the same population in 1980, but the latter two have skyrocketed ahead since then for example). What’s more, the South’s major metros score better on diversity and attracting immigrants than the Midwest’s major metros as a general rule.

These charts show the convergence in incomes over time. The decline in relative income of the Midwest is possibly in part to increases elsewhere, not internal dynamics. But think about what the Midwest looked like in 1950, 60, or 70 vs the South, then think about it today and it’s night and day. The Midwest may still be endowed with better educational and cultural institutions than the South, but we can see where the trends are going. Keep in mind that those things are lagging indicators. Chicago didn’t get classy until after it got rich, for example.

Now we see that Southern income performance hasn’t been great since the mid to late 90s. This is a problem for them. As is their dependence on growth itself in their communities. I won’t claim that the South is trouble free or will necessarily thrive over the long haul. But they seem to have a clearer sense of identity, where they want to go, and what their deficiencies are than most Midwestern places.

Richard Longworth seems to buy the decline theory but has a different explanation of the source, namely that Chicago has sucked the life out of other Midwestern states:

In the global economy, sheer size is a great big magnet, drawing in the resources and people from the surrounding region. We see this in the exploding cities of China, India and South America. We see it in Europe, where London booms while the rest of England slowly rots.

And we see it in the Midwest where, as the urbanologist Richard Florida has written, Chicago has simply sucked the life – the finance, the business services, the investment, especially the best young people – out of the rest of the Midwest.

To any young person in Nashville or Charlotte, the home town offers plenty of opportunities for work and a good life. To any young person stuck in post-industrial Cleveland or Detroit, it’s only logical to decamp to Chicago, rather than to stay home and try to build something in the wreckage of a vanished economy.

This seems to be a common view (see another example), even in the places that would be on the victim side of the equation. But I’ve never seen strong data that suggests this is actually the case. Are college grads and young people getting sucked out of the rest of the Midwest into Chicago?

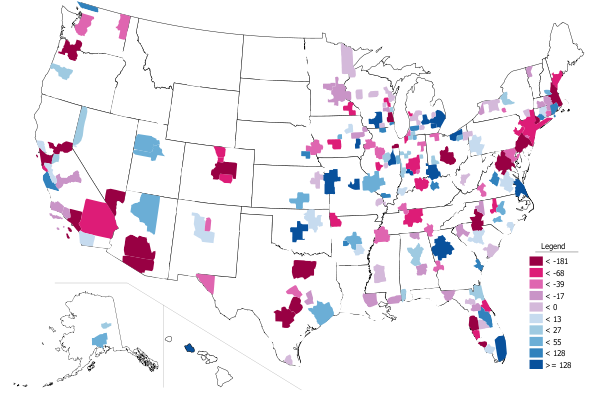

Thanks to the Census Bureau, we now have a view, albeit limited, into this. The American Community Survey releases county to county migration patterns off of their five year surveys sliced by attribute. There seems to be some statistical noise in these, and for various reasons I can’t track state to metro migrations, but thanks to my Telestrian tool, I was able to aggregate this to at least get metro to metro migration. So here is a map of migration of adults with college degrees for the Chicago metro area from the 2007-2011 ACS:

Net migration of adults 25+ with a bachelors degree or higher with the Chicago metropolitan area. Source: 2007-2011 ACS county to county migration data with aggregation and mapping by Telestrian

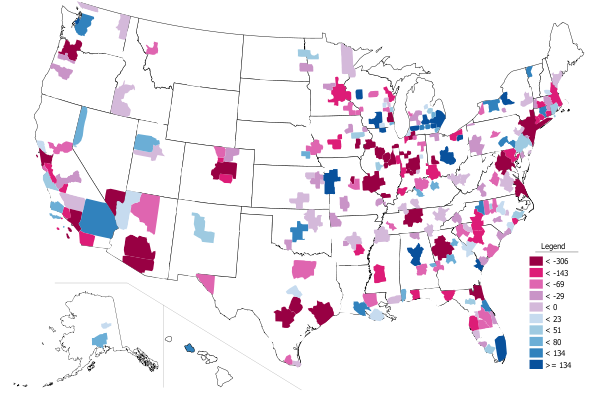

This looks like a mixed bag to me, not a hoover operation. What about the “young and restless”? Here’s a similar map of people aged 18-34:

Net migration of 18-34yos with the Chicago metropolitan area. Source: 2006-2010 ACS county to county migration data with aggregation and mapping by Telestrian

This is an absolute blowout, with a massive amount of red on the map showing areas to which Chicago is actually losing young adults. Honestly, this only makes sense given the well known headline negative domestic migration numbers for Chicago.

I do find it interesting that there’s a strong draw from Michigan. Clearly Michigan has taken a decade plus long beating. There’s been strong net out-migration from Michigan to many other Midwestern cities during that time frame, and its the same in Cleveland, which also took an economic beating in the last decade. This is just an impression so I don’t want to overstate, but it seems to me that a disproportionate number of the stories about brain drain to Chicago give examples from Michigan. Longworth uses the examples of Detroit and Cleveland. These would appear to be the places where the argument has been truly legitimate, but that doesn’t mean you can extrapolate generally from there.

What’s more, even if a young person with a college degree does move to Chicago from somewhere else, will they stay there long term? They may circulate out back to where they came from or somewhere else after absorbing skills and experience. It’s the same with New York, DC, SF, etc. I’ve said these places should be viewed as human capital refineries, much like universities. That’s not a bad thing at all. In fact, it’s a big plus for everybody all around. Chicago is doing fine there. But it’s a more complex talent dynamic than is generally presented, a presentation that does not seem to be backed up by the data in any case.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Photo courtesy of BigStockPhoto.com.