There are black urbanists. There are African-Americans who have invested their life's work toward the betterment of cities. They haven't always gotten the exposure and acknowledgement that others have received, but they have nonetheless contributed to an improved understanding of how cities work, especially in an African-American context.

Today, I'm putting forth a nomination list of ten individuals whose work may not conventionally fall in the realm of urbanism as it's known today, but certainly stands out as urban-oriented. And why is that? The work of the people listed below doesn't fall in the fields or disciplines most people associate with today's urbanists -- architects, landscape architects, urban designers, economists, and enlightened public works officials or policymakers. The ten I'm nominating as leading black urbanists tend to have sociological or activist backgrounds, often rooted in the Chicago School of sociology, which emphasizes the study of human interactions as opposed to the impacts of design, economy or policy on the built environment. And of course, the human interactions they most frequently observed were those of African-Americans within major cities.

Here they are, in (roughly) chronological order.

W. E. B. DuBois. As a sociologist, historian, civil rights activist and founder of the NAACP who was the first African-American to earn a doctorate (from Harvard, in sociology), DuBois' work as an activist is well-known. However, DuBois rose to prominence in 1899 with the publication of The Philadelphia Negro. The study, which helped to cement the field of sociology as an academic discipline, examined the form and function of Philadelphia's black community, which operated nearly completely out of the context of other urban communities. DuBois' study was among the first to openly say that discrimination was at the heart of problems within isolated black urban communities.

Horace Cayton, Jr./ St. Clair Drake. Cayton and Drake followed up the work of DuBois with their own Northern city sociological study, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City. Using Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood as their laboratory, Cayton and Drake provided not only a "generalized analysis of black migration, settlement, community structure, and black-white race relations in the early part of the twentieth century, but also tell us what has changed in the last hundred years and what has not." Cayton was the grandchild of America's first elected African-American senator who later went on to become a sociologist, newspaper columnist and author. Drake was a sociologist and anthropologist who later founded the African-American Studies program at Stanford University. The two met at the University of Chicago and produced their famed study.

John Hope Franklin. As an historian at several institutions throughout his career, Franklin did not specialize in cities per se. However, in works such as From Slavery to Freedom, first published in 1947, and his lecture series Racial Equality in America, he more than touches upon the African-American experience in cities, and how discrimination shapes the experience of black residents, and indeed the entire city.

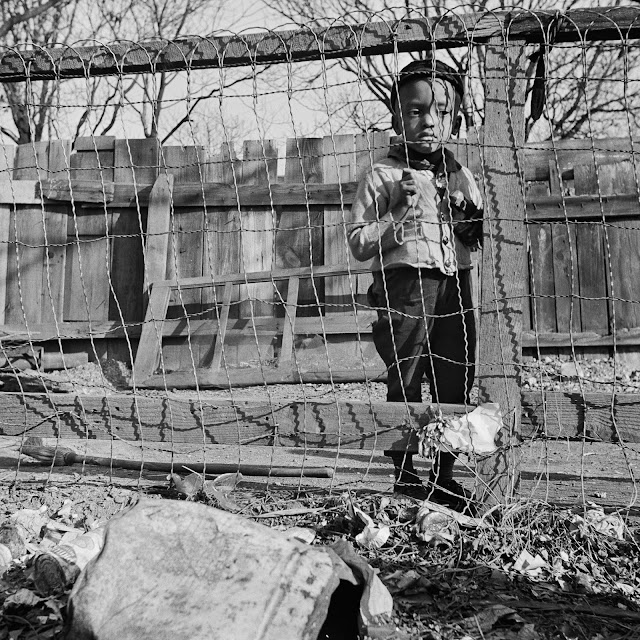

Gordon Parks. A photographer, writer and filmmaker, Parks specialized in documenting the everyday lives of African-Americans, especially in cities. His work often made a statement on the conditions of blacks in cities, and forced viewers to reflect on their condition:

Dorothy Mae Richardson. Richardson was a community activist who fought against redlining in her neighborhood in Pittsburgh, PA. Richardson challenged local Pittsburgh banks to issue conventional loans for mortgages and housing rehabs in her Central North Side neighborhood. That led to the founding of Neighborhood Housing Services in Pittsburgh, and the national group now known as NeighborWorks America, one of the nation's leading community development institutions.

Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts. Rev. Dr. Butts is the pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York, but in this context is more well-known as the founder and chairman of Abyssinian Development Corporation in New York as well. Founded in 1989, ADC is one of many community development corporations in New York and across the country that have sought to fill the investment void -- for housing, for commercial development, for community services -- in distressed communities. In ADC's case, the organization is credited with bringing in more than $500 million in housing and commercial development to New York's Harlem neighborhood since 1989.

William Julius Wilson. Following in the earlier sociological tradition of the study of blacks in cities, Wilson is sociology professor at Harvard University. Wilson is the author of many works, but perhaps his most influential include The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, The Underclass and Public Policy, which once again brought African-American community isolation to the forefront, and When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor, which examines the impact of job loss on poor communities. More recently, Wilson published More Than Just Race: Being Black and Poor in the Inner City, which more closely links urban poverty with discriminatory practices whose impacts linger today.

Geoffrey Canada. Canada is credited with vastly expanding the role of a traditional family-oriented social service agency to the Harlem Children's Zone, an organization that tightly tracts the academic success and family support of all families within a 24-block area in Harlem. The program is resource-intensive, but it is credited with stemming the tide against poverty in Harlem.

Mary Pattillo. Pattillo is a professor of sociology and African-American Studies at Northwestern University. She's added two important works that illustrate how blacks operate in today's urban environment. In 1999 she published Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril for the Black Middle Class, which documents how the black middle class has a far more difficult time achieving "escape velocity" from the ills of the inner city, and Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City, which illustrates how a uniquely African-American version of gentrification emerged in Chicago's North Kenwood-Oakland neighborhood on the South Side.

So there's ten black urbanists. I know there are many more; some who work with lots of notoriety as they address issues like police brutality, housing, public transit, environmental justice, food deserts and the like. And there are others who toil in anonymity, working in block clubs, CDCs and other organizations, working steadfastly to make their community a better place.

I made a statement three years ago that takes a shot as to why there are "no prominent black urbanists" today:

"I believe no nationally prominent black urbanist has emerged in large part because of differing worldviews held by whites and blacks. Very, very, very broadly speaking, with many caveats, I believe whites have a history of believing they can impact cities, while blacks have a history of believing that cities impact them."

By that I mean that I see many white urbanists surveying the urban landscape and developing rather abstract solutions that flow downward into actual policy, while many black urbanists assess conditions on the ground and develop solutions that they believe will rise up into actual policy. I hope at some point the two can meet and work together.

This post originally appeared at Corner Side Yard on July 7, 2015.

Pete Saunders is a Detroit native who has worked as a public and private sector urban planner in the Chicago area for more than twenty years. He is also the author of "The Corner Side Yard," an urban planning blog that focuses on the redevelopment and revitalization of Rust Belt cities.

Top photo: Google Earth view of Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood, on the South Side lakefront. Source: Google Earth.