The growth industries and professions of the future will shape our cities in very different ways to the industries and professions that shaped our cities in the past. There are profound implications for urban planning and property, if we’re ready for them.

The biggest growth industry for coming years and for the foreseeable future, the official forecasts all seem to agree on, will be in health care and social assistance. This includes professions from surgeons to GPs to nurses to child care or aged care, various therapies and counsellors, dental, and even laundry workers, cleaners and administrative support roles. Already our biggest single industry, it employs more than 1.5 million Australians. It grew by over 20% in the five years to 2015 and that rate of growth is unlikely to change going forward. Nearly half of everyone in this industry has a bachelor’s degree or some higher education qualification so they’re not all hospital cleaners – many will be skilled professionals.

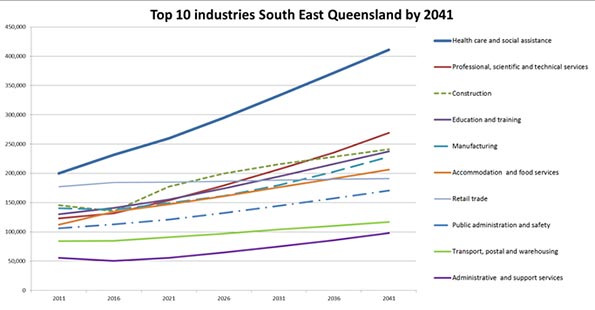

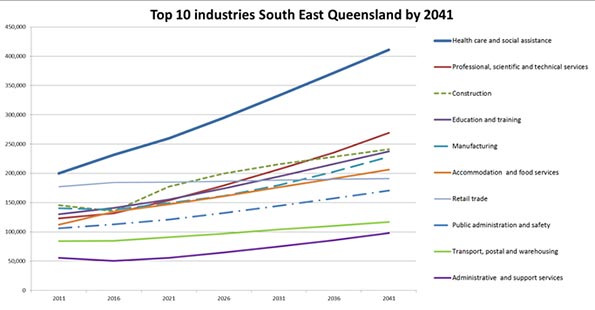

This will be followed by the professional, scientific and technical services industry and very close behind that, the education and training industry. Construction, manufacturing (yes, still growing despite all attempts to kill it off) and accommodation and food services round up the top six biggest growth industries of the future.

This is important because the nature of the growth industries of the future and where they will be located is going to reshape our cities in a very different way to the industries that grew with and shaped our cities in the past. This was highlighted in a recent report on employment in the growing region of South East Queensland, prepared by Macroplan for The Suburban Alliance.

The health care and social assistance industry is predicted by government authorities to grow more than any other industry in the years to 2041, producing around 220,000 extra jobs. But this industry has very different spatial needs to, say, the legal industry which has the highest inner city concentration of any occupation in the region. In health and social assistance, 200,000 of those 220,000 jobs will likely be in suburban business districts or otherwise scattered across suburbia. The biggest growth industry has little need or preference for clustering in the inner city.

Consider the implications for transport networks, property development and urban planning. Our urban model, reflecting a 100 years of employment centralization, is changing to one of employment dispersal. Jobs are not moving from the city centre to the suburbs but the industries which fuel growth are changing, and with them, the patterns of employment location.

Even in the professional, scientific and technical services industry, much of that future growth will occur outside the inner city. Take the generically titled occupation of “professional.” There were 284,300 of these in the South East Queensland region but only 24% of them in the inner city. A further quarter were in a number of defined suburban business districts and the balance – half – elsewhere in suburbia. This is our second biggest growth industry and those patterns of employment distribution are unlikely to change meaning of the 146,000 new jobs in this industry to be created to 2041, the clear majority will likely be suburban based.

The third biggest growth industry with education professionals also shows little evidence of centralization – only 7% of educators are inner city workers the rest are suburban. Even for those who describe their occupation as “Chief executives, general managers or legislators” there are only 21% of them in the inner city. And for clerical and administrative workers, it’s a similar picture: only 22% are inner city workers. The rest are suburbia based.

Engineers appear to have a preference for central locations with 42% of the 16,639 engineers of South East Queensland in the inner city as do the lawyers with 65% of them in the entire region to be found in the inner city. But there are only (fortunately?) just over 9,000 lawyers in the entire region so unless there’s to be an unpredicted explosion of work in the legal profession in the future it’s hard to see this occupation fueling demand for space and transport in the inner city of the future.

Fifty years ago, cities were full of clerical and administrative, managerial and professional workers, shuffling in to centralized offices on trams or trains or buses to clock on at 9am and clock off at 5pm. In the suburbs there were centres of manufacturing and heavy industry. In fifty years’ time, our cities will have different industries generating the bulk of jobs and many of those jobs will need to be based in suburban centres to be closer to their markets or regional transport arteries.

What’s that going to mean for urban planning, transport systems or property development? Will we see existing commercial and retail centres in the suburbs expand to accommodate a growing need for premises associated with health or medical professions, education or professional suites? Will our city centres evolve to become more entertainment, recreational and culture based hubs for the regions they serve, rather than largely just places of work?

There’s much more to be explored in this because the implications are profound. Sadly, much of our thinking around urban planning seems firmly rooted in traditional models which owe more to a sentimental rear vision view of urban development rather than a forward looking one.

Footnote: If you or your organization is interested in exploring what this means in more detail, or for specific regions, please just drop me an email. I’d be very interested to discuss with you. I’ve got a handy presentation which runs through all this in a bit more detail which I’d be happy to share.

Ross Elliott has more than twenty years experience in property and public policy. His past roles have included stints in urban economics, national and state roles with the Property Council, and in destination marketing. He has written extensively on a range of public policy issues centering around urban issues, and continues to maintain his recreational interest in public policy through ongoing contributions such as this or via his monthly blog, The Pulse.