African economies are in a race to get ahead of the demographic boom.

While some people in the United States are sweating the presence, against the backdrop of a demographically stagnant white population, of the 11 million undocumented immigrants or of the 30+ million other foreign-born residents, there are far bigger numbers brewing in other parts of the world, indeed numbers that are so large that they could affect decades from now the life of an American citizen far more than the rare determined Mexican or Guatemalan who manages henceforth to scale President Trump’s purportedly impenetrable border wall.

In the next decades as was so often the case in history, the future shape of the world could once again be decided in Europe and by Europe’s and the West’s handling of Africa’s incipient demographic boom.

In fact, if you are a generous-minded European who shares the Pope’s noble sentiment and who views the ongoing wave of migrants coming into your country as a benign and positive development; or, if you believe that borders are outdated constructs and that all refugees and other immigrants should be welcomed into the rich world; indeed, if it is your view that anyone who stands in the way of this openness is misguided by racist and nefarious motives, then it behooves you to test the strength of your belief by examining the larger demographic data coming out of Africa and Asia.

Because it is likely that your kindness and generosity will be, in the next decades, tested to their limits (unless they are limitless like the Pope’s). Because the two million people who have entered Europe on foot or via inflatable rafts in the past few years are, in scale, only thin vapor rising out of the demographic cauldron that is boiling up in Africa and south Asia. There are potentially many many more to come.

The Numbers

If Africa does not get its act together to start creating jobs at a rapid rate, there may be tens of millions more such people attempting to migrate in the future. The world population in 2015 stood at 7.3 billion and, on the UN’s medium variant, was expected to rise to 9.7 billion in 2050. Half of this 2.4 billion increase would take place in sub-Saharan Africa where the population will more than double in nearly every country.

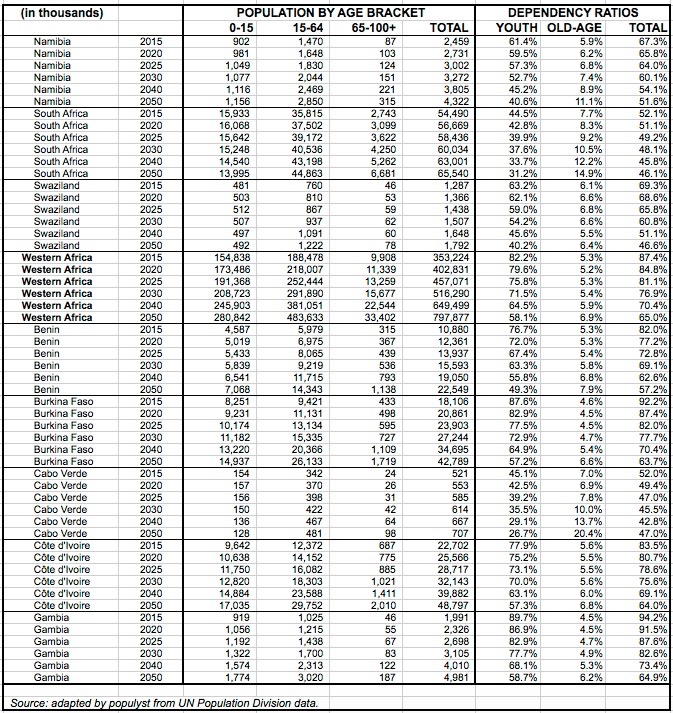

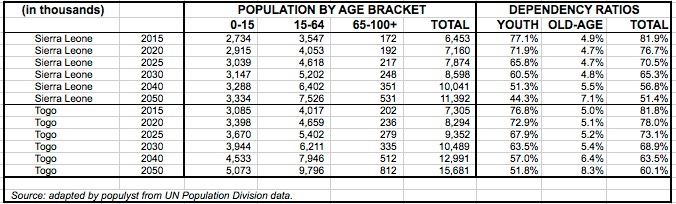

(See at the bottom of the article region and country tables derived from the UN’s medium variant).

Today sub-Saharan Africa has a billion people. In 2050, it will have 2.1 billion. Of more vivid concern is the fact that the working-age population, aged 15 to 64, will grow by 800 million people from 500 million to 1.3 billion. This 800 million increase is roughly equal to five times the current size of the US labor force.

It is possible that these numbers are too high. But it should be noted that, in arriving at these forecasts, the UN Population Division has plugged into its assumptions a significant decline in fertility rates across the sub-continent, from 4.8 children per woman today to 3.1 in 2050. On a constant-fertility scenario assuming no decline in the fertility rate, the population boom would be even larger. The working age population would rise to 1.6 billion (instead of 1.3 billion under the median variant) and the increase from today would then be equal to 1.1 billion (instead of 800 million). These are unimaginable numbers that are unlikely to materialize.

(See this article for the Total Fertility Ratio of every African country from the highest, Niger at 7.7, to the lowest, Mauritius at 1.5.)

In some ways, the precise magnitude of the boom is unimportant, so long as we accept that it will be somewhere between large and very large. Even a sanguine scenario that would halve the increase of the working age population from 800 million to 400 million would still present a challenge that African economies are today ill-equipped to handle. Economic conditions are insufficient even today to adequately feed, dress, educate and shelter the population.

One reason to feel some optimism is the fact that the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) also experienced a big rise in their working-age populations in the past thirty-five years and they managed to handle their demographic boom effectively. But this positive outcome was greatly assisted by a steep decline in China’s dependency ratio (DR) from 0.77 to 0.38. The DR is the ratio of dependents, children and the elderly, to working adults.

By comparison, the DR of sub-Saharan Africa is projected to fall from 0.86 today to a still elevated 0.63 in 2050. The decline in the youth DR (see tables below) is somewhat offset by a rise in the old-age DR that is itself due to an expected increase in life expectancy.

Certainly, if African fertility falls faster than median variant estimates, the total DR would decline more rapidly and there could be a faster acceleration in job creation and in GDP per capita.

(See at the bottom of the article the change in the dependency ratio for every country).

The Drive for Change

Africa is a wealthy continent but its wealth is highly concentrated in the hands of a few and it is often domiciled outside of Africa, in offshore financial centers, and in real estate and other assets all over the developed world. For decades, this configuration has worked wonders for Africa’s rulers and their entourages.

If the above numbers are correct, that configuration is not sustainable in the long run. Not only will there be many more Africans in the future than in the past, but the advances in global connectivity through the internet and mobile phones mean that these future Africans will be much more aware of the prevailing living standards in the rich world. Even now, each has in the palm of his hand a direct visual connection to Europe, the United States and other prosperous places. They have seen what a rich society looks like and they want their own place within it.

So what are the steps that can be taken to improve conditions in Africa? They can be summed up as the following:

• Fight corruption and cronyism. They divert capital to a small percentage of the population, capital that should be re-invested within Africa.

• Stop or reduce capital flight from poor to rich countries. A lot of Africa’s money is parked in offshore bank vaults, real estate projects or trophy property in the West.

• Raise confidence among foreign investors. With less corruption and clearer exit strategies, foreign money would flood into Africa.

• Institute a more inclusive form of governance that helps spread power and wealth away from the elite and to a greater segment of the population.

• Create or reinforce an independent judiciary, strengthen the rule of law, including respect for contract law and property rights.

• Invest in infrastructure. Africa needs trillions of dollars for projects ranging from power generation and water treatment plants to new roads and transportation systems.

• Boost literacy to rich-country levels, and close the gender gap in literacy. There is a strong correlation between female literacy and fertility. The greater the literacy, the lower the number of children per woman.

• Lower fertility. There is also a strong correlation between fertility and GDP per capita. Several countries like China that experienced a sharp decline in fertility enjoyed a significant demographic dividend.

Because there is now on the one hand an entrenched elite that may not easily let go of its privileges and on the other hand enormous demographic pressure on the economy, it is becoming clear that the current configuration is no longer sustainable. Either Africa gets on the fast road to modernization and industrialization, or the continent could suffer dislocation and instability at a near unimaginable scale.

There is certainly a strong desire by many foreign parties to invest in Africa, but there is a lack of confidence in one’s ability to recover the investment with or without a profit. This major hurdle can be overcome by modernizing Africa’s institutions and its financial system, and as importantly by attacking corruption and cronyism.

Tables

The data below were compiled by populyst from the UN Population Division’s medium variant. Note that in sub-Saharan African in 2015-2050:

• the youth population (under 15 years old) is not quite doubling.

• the working-age population (15 to 64) is more than doubling.

• the elderly population (over 64) is more than tripling, albeit from a low base.

In the world overall, the under 15 number will be stagnant, the 15-64 will grow by 25% and the over 64 will more than double.

This piece originally appeared on Populyst.net

Sami Karam is the founder and editor of populyst.net and the creator of the populyst index™. populyst is about innovation, demography and society. Before populyst, he was the founder and manager of the Seven Global funds and a fund manager at leading asset managers in Boston and New York. In addition to a finance MBA from the Wharton School, he holds a Master's in Civil Engineering from Cornell and a Bachelor of Architecture from UT Austin.

Photo: Lars Rohwer (Lars Rohwer - per OTRS) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons