The 2007 housing crisis was particularly tough on African-Americans, as well as Hispanics, extinguishing much of their already miniscule wealth. Industrial layoffs, particularly in the Midwest, made things worse.

However the rising economic tide of the past few years has started to lift more boats. The African-American unemployment rate fell to 6.8% in December, the lowest level since the government started keeping tabs in 1972. Although that’s 3.1 percentage points worse than whites, the gap is the slimmest on record. A tightening labor market since 2015 has also driven up wages of black workers, many of whom are employed in manufacturing and other historically middle and lower-wage service industries.

There's still much room for economic improvement for the nation's black community -- the income gap with whites remains considerably higher than it was in 2000, with the median black household earning 35.5% less -- but as we pay homage to Martin Luther King this week, the record low unemployment rate is a cause for celebration.

President Trump has predictably taken credit for the good news, but kudos more likely should go to those states and metropolitan areas that have created the conditions for black progress.

The gains have not been evenly spread. To determine where African-Americans are faring the best economically, we evaluated America’s 53 largest metropolitan statistical areas based on three critical factors that we believe are indicators of middle-class success: the home ownership rate as of 2016; entrepreneurship, as measured by the self-employment rate in 2017; and 2016 median household income. In addition, we added a fourth category, demographic trends, measuring the change in the African-American population from 2010 to 2016 in these metro areas, to judge how the community is “voting with its feet.” Each factor was given equal weight.

The South Also Rises

One of the great ironies of our time is that the best opportunities for African-Americans now lie in the South, from which so many fled throughout much of the 20th century. In the past few decades, many good jobs have moved South and blacks, like many whites and Hispanics, have followed.

The South dominated the previous version of this ranking, developed through the Center for Opportunity Urbanism, three years ago, and still does. All of the top 10 metro areas are in the South, led in a tie for the No. 1 spot by Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV and Atlanta, which was our previous leader.

Washington, with its ample supply of well-paid federal jobs, is the metro area where blacks have the highest median household income in the nation: $69,246. Amid rising home prices, the black home ownership rate has dipped to 48.3% from 49.2%, but that’s still fourth highest among the largest metro areas.

Atlanta, with its historically black universities and strong middle class, has long been described as the black capital of America, and its thriving entertainment scene has given rise to claims that it’s become a cultural capital as well. Entrepreneurship is strong, with some 20% of the metro area’s black working population self-employed, the highest proportion in the nation, and though median black household income is quite a bit lower than in the D.C. area at $48,161, costs are lower too. In-migration has slowed since the financial crisis, but the black population is still up 14.7% since 2010.

Atlanta and Washington are followed in our ranking by Austin, Texas, Baltimore and Raleigh, N.C., with the rest of the top 20 rounded out exclusively by Southern cities, except for Boston in 19th place.

Two key determinants seem to be driving these rankings: homeownership and self-employment, traditional benchmarks of entering the middle class. All of the top 10 boast homeownership rates that match or well exceed the black national average of 41 percent. (It should be noted that the national average is a full third lower than the national average for all ethnicities.)

These patterns hold up as well for income. Black incomes have been rising most rapidly since 2010 in largely fast-growing Sun Belt locales, as analyst and Forbes contributor Pete Saunders has found, such as Nashville, Raleigh and Austin. It appears as if the fastest income gains are generally being made in the places where other ethnic groups are advancing as well. After Washington, the metro areas where blacks have the highest annual household incomes are San Jose ($65,400), the capital of Silicon Valley, and No. 4 Baltimore ($53,200), which like Washington has a huge federal employment base.

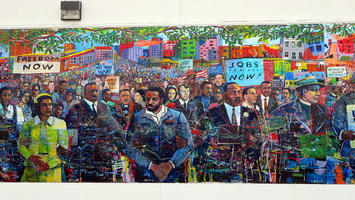

Gallery: Where African-Americans Are Doing The Best Economically

The New Great Migration

Perhaps the most persuasive indicator of African-American trends lies in population growth. During the period of the Great Migration out of the south in the early 20th century, an estimated 6 million blacks headed north and west to cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and St. Louis. But now the tide is reversing, with the African-American population dropping in the latter three over the past six years, as well as in San Francisco and cities with fading industrial cores like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit and Milwaukee.

In contrast the metro areas whose African-American populations have expanded the most since 2010 are the South and Sun Belt: Las Vegas, Dallas-Fort Worth, Austin, Phoenix.

In some cases it’s clear that blacks are leaving for better economic opportunities. In others, high housing prices may play a role: In Los Angeles and San Francisco the black homeownership rate is about 9 percentage points lower than the major metro average.

In San Francisco the black community seems headed toward irrelevance and extinction as tech workers have driven up home prices to unprecedented levels; the metropolitan area's African-American population has dropped 6.3% from 2010.

The situation is particularly dire in California where strict land-use and housing regulations have been associated with increases in home prices relative to income of 3.5 times the rest of the nation since 1995. In coastal California, African-Americans face prices from more than two to nine times their annual incomes than non-Hispanic whites. African-American homeownership rates in California are down 17% in the Golden State compared to a decline of 11% for Hispanics and 6% for non-Hispanic whites. Asian homeownership rates have stayed the same.

Blacks, like many other Americans, are likely to continue to move, as Pete Saunders notes, to cities that are both high growth and relatively low cost. In these cities, housing and land use policies generally allow the market to function, resulting in lower home prices and greater housing choice. Business investment and job creation are also strongly backed. Blacks, like others, are moving to these places for opportunity.

In many cases this means a reversal of the Great Migration and a return trip to parts of the country now far more accommodating to black aspirations than those places which once provided the greatest opportunities.

This piece originally appeared on Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Ann Fisher, via Flickr, using CC License.