The May 21 Federal Election in Australia saw the sitting conservative party (the Liberals) ousted from office, and the left-wing opposition Australian Labor Party claiming victory. In the process, what was once a relatively minor division between increasingly privileged professionals of inner urban electorates and the working- and middle-class suburban and regional voters, widened into a chasm. This may have been a permanent tectonic shift. Traditional political allegiances which have more or less endured for near a century, may now be a thing of the past. A new political geography has emerged, with inner urban and high wealth areas turning to support more radical leftist parties which have been steadfastly resisted by the suburbs and regions. Place now defines politics, more than occupation, education, religion or family history.

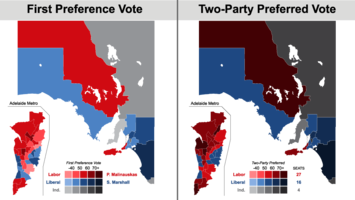

To understand how much has changed, American readers need to understand that under our system of preferential voting, voters are given second, third, fourth and even fifth choices (or more, depending on the number of candidates in each electorate). If your #1 choice candidate has insufficient votes, your vote is then given to your second preference candidate. If your second preference is similarly unpopular, your vote goes to your third preference, and so on. In years past, it was more common for many candidates in “safe” major party aligned seats to win more than 50% of the primary vote, meaning they were elected without preferences.

In this latest election however, the Labor Party have been awarded government of the country with less than a third of the national primary vote – itself a revelation and evidence of how important preferential voting has become. There are 151 House of Representative (lower house) seats in Australia. Thanks to preferences, Labor have claimed 76 (with some still undecided) which is more than half, thus giving them the responsibility of leading the nation.

The preferential system also means that one candidate may receive 40% of the primary votes, and other candidates might receive 35% and 25% respectively, but the candidate with the most primary votes may still not win. If just half the preferences of the candidate with 25% of the vote flow to the one with 35% of the vote, that candidate can claim 47% and defeat the candidate who actually got more primary (first votes).

This preference flow can work in favour of a range of minor parties and independents as our most recent election proved. A swathe of progressive and left leaning minor parties and independents were elected this time, nearly all of them in affluent or inner urban seats, where they may have received as little as 25% of the primary vote but still won due to preferences.

The Greens are one minority party which have usually gained around 10% of the total primary vote across the country. Campaigning for radical left/green agendas (some of which would make US Democrats blush), their strengths have been in the inner cities, where the wealthiest Australians typically live. Boasting high incomes, low unemployment, eye watering house prices, an abundance of private schools and excellent inner urban medical care now seems a precondition for supporting radical environmental and leftist political agendas. The green voter is no longer the radical hippy with tie-dye clothes and Rasta hair – they are more likely a highly paid white-collar professional who lives in a stylish inner-city residence and who prefers to holiday overseas or at exclusive beachside communities (along with other similarly privileged and entitled professionals, wearing white linen resort wear, naturally).

The top 10 green voting seats reads like a roll call of the wealthy and privileged: the seat of Melbourne (inner city) recorded a 51% primary vote to The Greens; Griffith (inner Brisbane) recorded 36%; Ryan (a middle suburban, leafy and wealthy seat in Brisbane’s west) with 31%; Macnamara (Melbourne CBD south) 31%; Brisbane (inner city) 28%; Wills (Melbourne inner north) 28%; Cooper (Melbourne inner north west) 28%; Richmond (wealthy coastal resort communities in New South Wales) 25%; Canberra 25% and the seat of Sydney (CBD inner) 23%.

In addition to The Greens, this election saw a raft of independents campaign under a united banner as “Climate 200” using the colour teal to distinguish themselves. They campaigned for 50% carbon emission reductions by 2030 (a near impossibility) among other things. The Teals were funded by Australian billionaire Simon Holmes a Court (who largely inherited his money) and were all white, privileged, nearly all women, and from well-to-do seats. They proved enormously successful winning big in seats more traditionally aligned with the conservative Liberals (who they rejected both on climate policy and for some poor messaging on women’s issues by the Liberals). They polled strongly in seats like Warringah (harbourside Sydney where homes are valued in the tens of millions) with 45% of the primary vote; then leafy Kooyong (similarly wealthy inner Melbourne seat) with 42% of the vote; and Mackellar (Sydney northern beaches) 39%; Wentworth (like Warringah but Sydney harbourside south) 37%; Goldstein (Melbourne inner south) 36%; Curtin (Perth inner north coastal) 31% and North Sydney (inner urban) 25%.

As a result, Australia’s electoral map has been comprehensively redrawn. Seats with the wealthiest profiles, especially if they are inner city electorates, have nearly all swung in favour of progressive minor parties expressing the strongest views on climate, gender, race, society, faith, and other values. For the conservative liberals, this has meant losing traditional heartland seats. For the left-wing Labor Party, it is also a problem in that they have relied heavily on the preferences of these groups to be able to win government with less than a third of the primary vote. Labor will need their support and no doubt in turn be asked to support policies that, while fashionable with wealthy inner urban professionals, could hurt Labor’s traditional working-class voters. High household energy costs and lost jobs in the mining sector are just the start of that policy tension.

This could also mean that middle and outer suburban seats, and those based around regional cities, may be more hotly contested by major parties in the future. Greens and Teals and other independents may prove too hard to unseat from their inner urban fortresses – they can criticise on one hand and promise with the other, playing an attractive populist card but will never be in a position to form a government. And if the major parties on the left or right try to stretch their policy appeal such that it is sufficiently radical to win back inner urban progressives, they risk losing the faith with working- and middle-class families outside the urban bubbles.

As one Liberal anonymously commented after the result: “If the Liberals try to chase the teal vote, then the party is over.”

“It’s like what happened to Labor, which was set up to look after the working class, but which found itself in the wilderness as the progressive left started joining and dragged them into internal fights about elite issues versus looking after ordinary people.”

The inner urban cognoscenti of media, academics, professionals and artists may celebrate the election result, but large sections of a once egalitarian Australia may find themselves increasingly removed from those inside the bubble, who claim to know better. It is not a good recipe for long term stability.

Ross Elliott has more than thirty years' experience in urban development, property and public policy. In addition to his consulting work he is Chair of the Lord Mayor of Brisbane's Better Suburbs Initiative, a director of The Suburban Alliance, and District Chair of the ULI in Brisbane, Australia. His past roles have included a number of industry leadership positions. He has written and spoken extensively on a range of public policy issues centering around urban issues, and maintains his interest in public policy through ongoing contributions such as this or via his monthly blog, The Pulse.

Photo: Erin via Wikimedia under CC 4.0 License.