A well-intentioned but quixotic presidential vision to make high-speed rail service available to 80 percent of Americans in 25 years is being buffeted by a string of reversals. And, like its British counterpart, the London-to-Birmingham high speed rail line (HS2), it is the subject of an impassioned debate. Called by congressional leaders "an absolute disaster," and a "poor investment," the President’s ambitious initiative is unraveling at the hands of a deficit-conscious Congress, fiscally-strapped states, reluctant private railroad companies and a skeptical public.

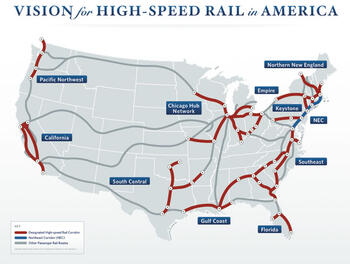

The $53 billion initiative was seeded with an $8 billion "stimulus" grant and followed by an additional $2.1 billion appropriation out of the regular federal budget. But instead of focusing the money on improving rail service where it would have made the most sense— in the densely populated, heavily traveled Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington— the Obama Administration sprinkled the money on 54 projects in 23 states.

Some of the awards are engineering and construction grants but many more are simply planning funds intended to plant the seeds of future passenger rail service across the country. Only two of the projects could be called truly "high-speed rail" because they would involve construction of dedicated rail lines in their own rights-of-way where trains could attain speeds of 120 mph and higher. The remaining construction money will be used to upgrade existing freight rail facilities owned by private railroad companies (the so-called Class One railroads) to allow "higher speed" passenger trains to run on track shared with freight carriers.

Many of the proposed improvements will result in only small increases in average speed and in marginal reductions in travel time. For example, a $1.1 billion program of track improvements on Union Pacific track between Chicago and St. Louis is expected to increase average speeds only by 10 miles per hour (from 53 to 63 mph) and to cut the present four-and-a-half hour trip time by 48 minutes. A $460 million program of improvements in North Carolina will cut travel time between Raleigh, NC and Charlotte, NC by only 13 minutes according to critics in the state legislature.

Shared-track operation has raised many questions in the minds of the intended host freight railroad companies. Railroad executives are concerned about safety and operational difficulties of running higher speed passenger trains on a common track with slower freight trains and they are determined to protect track capacity for future expansion of freight operations. Their first obligation, they assert, is to protect the interests of their customers and stockholders. This has led to protracted negotiations with state rail authorities in which the private railroads are fighting Administration demands for financial penalties in case passenger train operations fail to achieve pre-determined on-time performance standards. In some cases, negotiations have hit an impasse causing the Administration’s implementation timetable to fall behind. In other cases, freight railroad companies have reluctantly given in, not wishing to alienate the White House or fearing its retaliation.

A serious blow to the presidential initiative was delivered by a group of three determined, fiscally conservative governors who rejected billions of dollars in grant awards because they were concerned that the proposed passenger rail services could require large public subsidies to keep the passenger trains operating. In the U.S. federal system, the governors and state legislatures have the final say concerning construction and operation of public transportation services within state boundaries. The refusal of the governors of Wisconsin, Ohio and Florida to participate in the White House HSR program thus took much wind out of the sails of the Administration initiative.

Perhaps the most serious blow was delivered by Governor Rick Scott whose state of Florida was supposed to host one of the Administration’s showcase projects: an 86-mile true high-speed rail line, built in its own right-of-way in the median of an interstate highway between the cities of Tampa and Orlando. A score of international rail industry giants converged on Florida in the expectation of participating in a rich bonanza of contract awards and a chance to bid on a future rail extension from Orlando to Miami.

But they came to be disappointed. A study conducted by the libertarian think tank, the Reason Foundation, convinced Governor Scott that the project could involve serious cost overruns and the risk of continuing operating subsidies. This caused the Governor to decline the federal grant, thus putting an effective end to the project. A last-minute effort by rail supporters to challenge the Governor’s decision was stopped in its tracks when the state supreme court upheld unanimously his right to veto the project.

This left the Administration with just one true high-speed rail project: California’s proposed 520-mile high-speed rail line connecting Los Angeles with Northern California’s San Francisco Bay area and Sacramento. The origin of this venture dates back to 2008 when voters approved a $9.95 billion bond measure as a down payment on the $43 billion system. Since then the project became mired in multiple controversies. One relates to a lack of a clear financial plan, another to what critics, including the state’s official "peer review" panel, claim to have been overly optimistic forecasts of construction costs, ridership and revenues. Then came a report raising questions about the escalating price tag for the project which now is estimated at $66 billion. This is occurring in a state that is staggering beneath a $26 billion deficit.

In the face of fierce opposition that developed in the wealthy Bay Area communities lying in the proposed path of the rail line, the sponsoring agency, the California High-Speed Rail Authority, decided to start construction in the sparsely populated and economically depressed Central Valley, where land is relatively cheap, unemployment is high and community opposition was expected to be minimal. The decision was spurred by demands from the Obama Administration that its $3.6 billion grant result in a rail segment that has "operational independence." The first 123-mile stretch, to be built between Fresno (pop. 909,000) and Bakersfield (pop. 339,000), was quickly derided by critics as a "railroad to nowhere." Even in the low-density Central Valley, the expected disruption caused by the project to communities, farms and irrigation systems has stirred political opposition. Its future – as indeed the fate of the entire $43-66 billion (take your pick) venture – is shrouded at this point in uncertainty.

The same can be said of President Obama’s high-speed rail initiative as a whole. Just as the proposed £32 billion high-speed rail link between London and Birmingham has been called an "expensive white elephant" and a "vanity project," so the White House high-speed rail initiative is being criticized as a "boondoggle" and derided as a monument to President Obama’s ambition to leave behind a lasting legacy à la President Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System. Editorial opinion of major national newspapers has turned critical as have many influential columnists and other opinion leaders. A number of senior congressional leaders – including the third-ranking Republican in the House, Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy, and the chairman of the influential House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, John Mica, have likewise openly criticized the initiative as wasteful and poorly executed.

Even elected representatives from states that would potentially benefit from the government’s largesse have been skeptical about plans for high-speed rail in their states. "Blindly committing huge sums of money to this project will not make it worthwhile, and to do so at this time would be premature and fiscally irresponsible," wrote one member of the congressional delegation from the state of New York. Members of the North Carolina legislature have introduced a bill to bar the state department of transportation from accepting $460 million in federal high-speed rail funds, pointing to the meager trip time savings resulting from the proposed rail projects and the potential need for operating subsidies.

As this is written, Capitol Hill observers give the high-speed rail program only a small chance of obtaining additional congressional appropriations in Fiscal Year 2012 and beyond. A March 15 report in which the congressional House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure discusses its views of the forthcoming Fiscal Year 2012 transportation budget, the Obama Administration's proposed $53 billion high-speed rail program is not even mentioned. Turning off the spigot of federal dollars next year would effectively starve out the Administration’s rail initiative.

The President’s proposal came at a most inopportune time, when the nation is recovering from a serious recession and desperately trying to reduce the federal budget deficit and a mountain of debt. In time, however, the recession will end, the economy will start growing again, and the deficit will hopefully come under control. At that distant moment in time, perhaps toward the end of this decade, the nation might be able to resume its tradition of "bold endeavors" — launching ambitious programs of public infrastructure renewal.

That could be an appropriate time to revive the idea of a high-speed rail network, at least in the densely populated Northeast Corridor where road and air traffic congestion will soon be reaching levels that threaten its continued growth and productivity. For now, however, prudence, good sense and the common welfare dictate that we, as a nation, learn to live within our means.

Ken Orski has worked professionally in the field of transportation for over 30 years.

Stop content thief

Plagiarism Avenger can prevent content thief. STOP Content Thieves from Ranking Above You! Plagiarism Avenger Review

Nobody Thinks

Having worked with numerous transit districts and rail operations all over the country, including those in St. Louis, I can comment on some of of these points from a professional perspective:

A reduction in the travel time between Chicago and St. Louis by 48 minutes equates to a 20% increase in speed. That's huge. Coal drags and freight running those tracks will move so much more revenue that the costs will be miniscule in the overall picture of the economy. Anyone thinking that the results of that spending is wasteful needs to have their head examined first, and secondly go to St. Louis and actually stand there and watch the train movements as I have.

Mixing freight and passenger on the same tracks has always been a "tragedy waiting to happen" and in fact has happened numerous times. In fact, that's one of the reasons I recommended against Bi-State Development Agency (Now METRO) not initiate commuter rail on the Burlington-Northern trackage in Missouri, because they would be running against heavy freight and coal drags on the same tracks. Even with some areas of double trackage, it's a problem due to scheduling, passing times, and the length of the coal drags and freights vs. commuter rail and passenger trains.

Double trackage has always been a dream on every line. The likelihood of it happening in many areas is nil simply due to cost and space. Part of that was the short-sightedness of the railroads when they originally laid track, leaving room for but a single track. Secondly was the lack of foresight by many communities, even my our own and adjoining ones, in allowing building right up to the track right of ways. So double tracking with necessary right-of-way is almost impossible.

Then we get into high speed rail. The buffer between existing rail lines and structures is such that we'll never see it here on the existing West Coast lines. Won't ever happen. Maybe inland somewhere where there is no building so far. Complaints about the Northeast Corridor? Complain about Amtrak, the near bankrupt or bankrupt quasi-federal rail program that runs the Acela high speed train that doesn't run part of the time, and when it does, breaks down or isn't on time? What's with that? It's not like they don't have a high speed train that they spent billions developing and modifying the rail beds for. It just doesn't work, like most of the things the government does. Plus, they want people to pay a premium for taking a train that doesn't run most of the time?

We need good old fashioned rail service, commuter rail and light rail that actually takes us where we want to go, safely and securely. We need bus and paratransit interface at stations that connect so we can schedule to go shopping, to appointments, leisure activities and home without spending the entire day traipsing on and off buses trying to get to a destination.

Why are some cities building successful rapid transit while others sit with their fingers in some dark orifice? Because too many politicians get involved with personal agendas instead of building good reliable public transit. Maybe a look at each of their personal stock holdings and retirement accounts would reveal a lot about why they love concrete and gasoline so much?

Good.

A Total Waste of Money.

Dave Barnes

+1.303.744.9024

WebEnhancement Services Worldwide