Ryan Avent hits a home run, strikes out and earns a "yes, but," all in the same article ("One Path to Better Jobs: More Density in Cities") in The New York Times.

A Home Run on Housing Regulation: Avent rightly notes that the land-use and housing regulations of metropolitan areas like San Francisco have not only driven housing prices higher, but also negatively impacted economic growth. Studies in the UK, the US and the Netherlands have demonstrated that significant restrictions on land use (called smart growth or urban containment) lead to reduced employment and economic growth in metropolitan areas. His comparison to OPEC is "right on" – that metropolitan areas like San Francisco have squeezed the supply of housing, which, of course, drives up house prices, just as restricting the supply of any good or service in demand will tend to do. Avent is also right in noting that high housing prices have driven huge numbers of people out of the San Francisco Bay Area to places like Phoenix. According to the Census Bureau, nearly 2,100,000 people moved from Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and San Jose between 2000 and 2009 to other parts of the country.

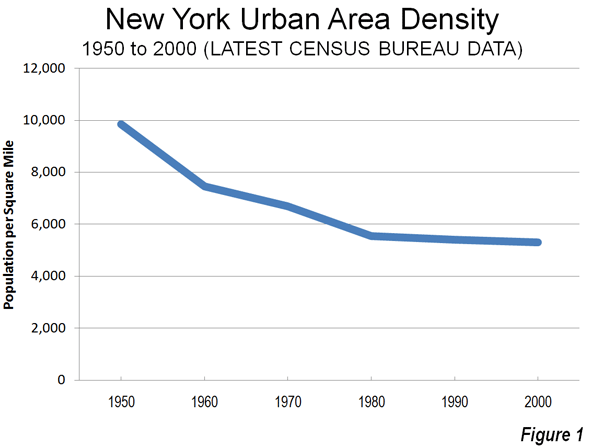

Striking Out on Density: The strikeout results from assumptions that are patently wrong. Cities (urban areas) do not get more dense as they add population. They actually become less dense. For example, the New York urban area has added 50 percent to its population since 1950, yet its population density has dropped by 45 percent (Figure 1). Between 2000 and 2010, most metropolitan population growth, whether in San Francisco, New York, Phoenix, Portland or Houston, was in the lower density suburbs (see: http://www.city-journal.org/2011/eon0406jkwc.html ). The same dispersion is occurring virtually around the world (see: http://www.demographia.com/db-evolveix.htm), from Seoul, to Shanghai, Manila and Mumbai. Rapid urban growth would mean even further dispersion and lower densities, not the higher density neighborhoods Avent imagines. Nonetheless, allowing the more affordable detached housing that people prefer would likely lead to stronger economic growth and more affluent residents in the San Francisco and other over-regulated metropolitan areas.

A "Yes, But" on Productivity: Any comparison of incomes between metropolitan areas needs to take into consideration the cost of living. For example, the San Francisco Bay Area (San Francisco/San Jose) is one of the most expensive places to live in the country. The median house price is more than 2.5 times that of Phoenix, after accounting for income differentials. Avent does not control for the difference in the cost of living, which is largely driven by the higher cost of housing. The lower cost of living neutralizes much of the impact of lower incomes (such as in Houston) in metropolitan areas like Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Indianapolis, etc., where the OPEC model has not been applied to land use regulation.

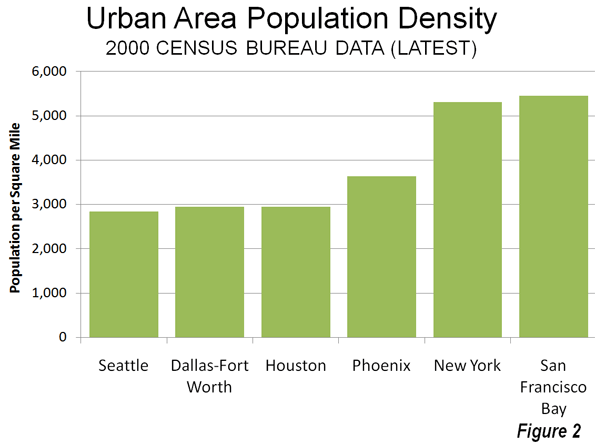

Finally, even controlling for the cost of living, there are substantial exceptions to any density-productivity thesis. For example, some of the greatest productivity gains information technology have come out of the Seattle area, which is the least dense major urban area in the 13 Western states, less dense than Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth and Phoenix. Even more impressively, Seattle's urban density is barely one-half that of New York or San Francisco (Figure 2), yet its gross domestic product per capita is higher than New York and within 2 percent of San Francisco/San Jose. Seattle's substantial contribution to the nation's productivity has occurred while its population density was declining nearly 15 percent (since 1980).

Avent, like many analysts before appears to presume that population growth means higher densities. In fact, urban areas grow by dispersing, not densifying.

Knowledgeable Post

btelefonkatalogen.biz

Word or story problems give us a first glimpse into how mathematics is used in the real word. To be solved, a word problem must be translated into the language of mathematics, where we use symbols for numbers - known or unknown, and for mathematical operations.

Ryan Avent hits a home run,

Ryan Avent hits a home run, strikes out and earns a "yes, but," all in the same article ("One Path to Better Jobs: More Density in Cities") in The New York Times.

A Home Run on Housing Regulation: Avent rightly notes that read Beelzebub manga the land-use and housing regulations of metropolitan areas like San Francisco have not only driven housing prices higher, but also negatively impacted economic growth. Studies in the UK, the US and the Netherlands have demonstrated Fairy Tail watch that significant restrictions on land u

Generally I don't learn

Generally I don't learn article on blogs, however I would like to say that this write-up very pressured me to check out and do so! Your writing taste has been amazed me. Thank you, quite nice article. - hotel bandungan

When cities get too big

Interesting counterpoint on urbanization/density bringing more productivity from a blog by Smart+Connected Communities Institute:

"Diseconomies of Scale?" by Martijn Moerbeek on Aug 22, 2011 about Latin America megacities.

http://www.smartconnectedcommunities.org/blogs/strategicperspectives/201...

Quoting, "Indeed, large cities attract the most talent, inward investment and are able to create network effects that drive productivity and economic growth.

"Nevertheless, once a city reaches a certain critical mass, the virtuous circle driven by economies of scale stalls or, even worse, starts to tail of as diseconomies of scale come to the fore."

Article goes on to talk about places like Sao Paulo and Mexico City.

My impression of U.S. and Canadian cities is that there is ample opportunity for productive business expansion in smaller urban regions and on the fringes of the bigger places where services are not necessarily delivered by regional bureaucracies becoming non-productive with increasing age and growing size.

Sprawl has had too much bad press

The only reason US cities have been so productive as they have grown, is BECAUSE of "sprawl" and automobility. No other cities in whatever country, are going to match these outcomes without doing it the same way.

"Monocentric" thinking is a disastrous bane of the urban planning profession. Agglomeration efficiencies CAN be outweighed by congestion inefficiencies. The solution is to reap TYPE-specific agglomeration efficiencies at multiple locations, each with a lower level of congestion than if you had all or most employment crammed into one central location.

This is actually the natural, "free market" ways in which cities develop if the "planners" will let them. Silicon Valley simply never would have happened in Manhattan.

The problem that cities in developing nations are coming up against, is that they simply have not matched the virtuous circle of development that most US cities went through post WW2, and indeed many cities in Europe did the same. That is, households and businesses were able to access the cheapest land in the history of urban development, land converted from agricultural use with a minimum of "planning gain", via roads and affordable automobile travel. Most cities in developing nations have been unable to enjoy the same process, because development processes are riddled with corruption and politicisation, and "planning gain" renders the process nowhere near as economically beneficial. (Many first world cities have lately reverted to this destructive situation thanks to "anti sprawl" mania; hence unaffordable housing, reduced productivity, stagnating business sectors, etc).

Low cost land, automobility, and multi-agglomeration urban form, are the USA's best-kept secret economic advantage - they mostly are not aware of it themselves, let alone anyone else around the world.

Political antagonism to personal mobility often is an underlying reason that rails are preferred to roads, in developing countries. This, too, along with "monocentric" thinking, will keep those cities economies stuck in the 1930's. Political antagonism to personal mobility is an underlying motivation in developed-country anti-road advocacy too. There is simply no economic justification for it.