Observers and advocates on Long Island — New York's Nassau and Suffolk counties — have repeatedly used age group population estimates to bolster land use policies based on their preferred narrative. The assumption? Young adults are moving away from the region in large numbers due to the high cost of living, particularly housing prices. So, the story goes, the suburban pattern must be broken, and small, high density housing units must replace detached, single-family homes as the dominant urban form if young adults are to be retained.

When the Long Island Housing Partnership dedicated a dozen affordable housing units in Southampton town in 2007, a spokesperson explained. “We're losing our young from the ages of 20 to 34 at five times the national average. People can't stay because of the high cost of living.” The region's premiere daily, Newsday, editorialized a few years later, “Unless Long Island stops this brain drain, it won't prosper.”

In reality, explanations for the changes in the size of age cohorts from decade to decade amount to little more than speculation. Census estimates of the population by age group tell us next to nothing about if, when, where, or why people are moving or “disappearing.” The data is a static picture of population age groups as they exist in a given geography on a given day.

Demographers have long believed that the primary driver of changes in age cohorts are changing patterns of birth and death rates. For example, in 1980, there were 141,917 fewer children below the age of 10 than in 1970 in Nassau-Suffolk (484,145 vs. 342,228). This correlates roughly with the decline of 150,262 in the number of 10-19 year-olds between 1980 and 1990, the decline of 110,663 in the number of people between 20 and 29 years of age in the 1990s, and the decline of 107,657 in the number of people between the ages of 30 and 39 in the 2000s (441,008 vs. 333,351).

This makes perfect sense. Individuals born in the 1970s would be in their teens in the 1980s, in their 20s in the 1990s, and in their 30s in the 2000s. If there were 150 thousand fewer children aged 0-9 in the 1970s, one would expect there to be over 100 thousand fewer people in their 30s in the 2000s.

It is, in other words, the case that the sharp decline of twenty-somethings in the 1990s and of thirty-somethings in the 2000s is largely the result of the “birth dearth,” a sharp decline in the birth rate that Nassau-Suffolk experienced in the 1970s, the decade after the “baby boom” from 1947 to 1964. The 1970s birth cohort is wending its way through the life cycle.

Indeed, even as critics decry the “brain drain,” it looks like this pattern has started to partially reverse in Nassau-Suffolk. Because birth rates rose in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there has been a substantial increase in the number of people between 15 and 24 years of age in the past decade. The population aged 15-19 increased by 17.4 percent, between 2000 and 2010, while the 20-24 year-old group increased by 18 percent, for a total increase of 15-24 year-olds of 54,726 over the last ten years. If the correlation between housing costs and people in their early 20s was strong, it is unlikely that during a period when the median price of a single-family home increased by 66 percent (from $220,000 in 2000 to $366,000 in 2010), that the population in their early twenties would increase as well.

All of this is not to discount the importance of migration patterns, or the attractiveness of a particular region to those in a particular age group. But the misinterpretation of data can lead to misplaced policy priorities. In this case, it's generally believed that when young adults move away from a region it's unhealthy for the area, and that policies that encourage a reversal of the trend — “hip” downtowns, sports stadiums, entertainment venues, small attached housing units — should be put in place.

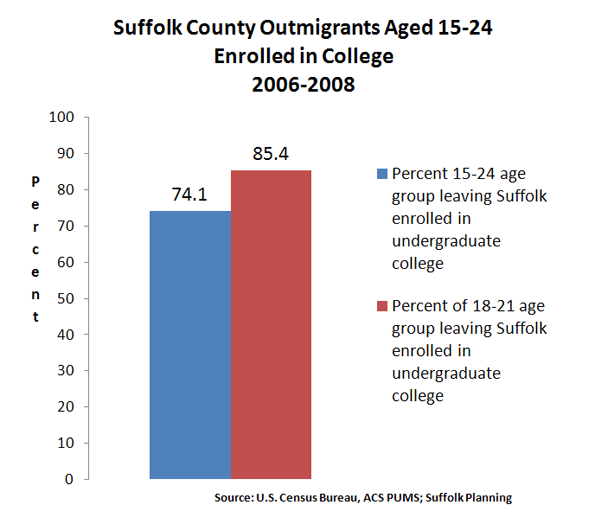

But numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, recently crunched for the Suffolk County Comprehensive Plan, show that 74.1 percent of 15-24 year-olds who move out of Suffolk are enrolled in college. When looking at only 18-21 year-olds, the primary college-aged group, the percentage of those leaving Suffolk because they're enrolled in college rises to 85.4 percent (see Figure 1).

Suffolk County had a college-going rate among high school graduates of 86.5 percent in 2010. Is this high rate something that needs to be reversed? Many of these college goers return to Long Island, sometimes after stints in New York or other cities as young careerists, and help to raise the median household income of migrants coming into Suffolk county to $81,471 (2008 dollars), compared to only $67,241 for those leaving Suffolk.

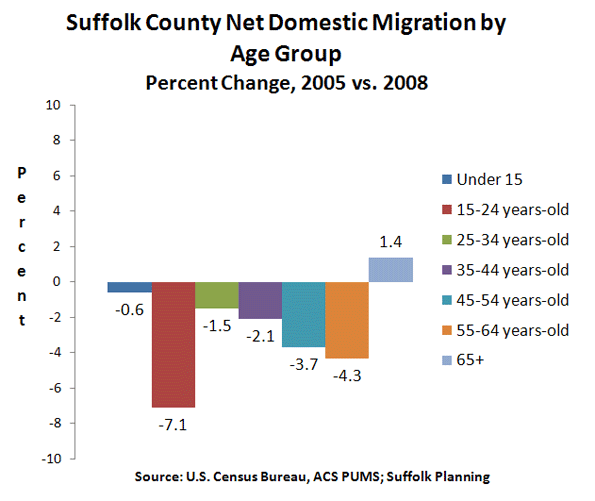

One more finding from the Suffolk Comprehensive Plan on domestic migration —movement within the United States — seems to mitigate against received wisdom. While the college-goers age group had the largest net domestic migration out of Suffolk, the second largest group was the 55-64 year-olds. (see Figure 2)

In other words, the age groups widely believed to be the most in danger of shrinking or “disappearing” due to outmigration are, according to the best available data, the least in danger of doing so. In general, the 25-34 and 35-44 year-old age groups are the smallest net domestic migration “losers,” because it is a relatively stable time in life. If people marry, and/or care for young children, move up the ranks of a career, or invest in a home, it is typically in these years that they do so.

As far back as 1978, Newsday screamed that “An Exodus of the Young Threatens Life-Style.” In fact, the 1970s saw a sharp increase in the number of young adults in Nassau-Suffolk; as the population aged 15-39 grew by 178,179, or 21 percent, from 846,070 in 1970 to 1,019,249 in 1980.

Demographic data can be a useful tool for policy makers attempting to clarify complicated public issues. But when data is not properly understood, or it is misinterpreted, then public policy debate is stymied.

Seth Forman, Ph.D, AICP, is author of American Obsession: Race and Conflict in the Age of Obama and Blacks in the Jewish Mind: A Crisis of Liberalism, among other books. His work has appeared in publications that include National Review, Frontpagemag.com, The Weekly Standard, and The American. He is currently Research Associate Professor at Stony Brook University, and the Chief Planner for the Long Island Regional Planning Council. His opinions are not associated with any of these institutions. He blogs at www.mrformansplanet.com.

Photo by SaraPritchard, Warped Tour'10, Long Island, New York

Good sharing. And today i

Good sharing. And today i would like to share one place to buy bags. where offer 65% discount off, 2011 new style, fast shipping and good service. Chatrandom.com

2 + 2 = 7?

Young, smart people are moving away to seek education and/or prosperity...and the local housing authority adds low-income housing? Isn't that like giving a grandfather clock to someone who wants to buy an iphone?

Increasingly, the solutions being offered to contemporary problems seem to be completely dissonant with the actual problems themselves. And, increasingly, the solutions seem to revolve around large, traditional developments like housing. What investor sold this idea to the Long Island Housing Partnership?

Decreasingly, the solutions seem to revolve less and less around jobs and upward mobility. It is as if this is now beyond our reach, so we instead go for comfort food: townhouses and mixed-use projects that resemble those of the past.

Urban evangelists now exhort cities to send "love notes" to their residents by adding parks or importing instant tradition from other places. The cynicism revolving around the urban condition is profound, and amounts to deafness. It's as if they have given up on our cities as places to work, and instead wish to build things that look good rather than function; now they garnish these corpses with flowers and call them our legacy.

Richard T. Reep, AIA, LEED-AP

Adjunct Professor, Rollins College

2011 President, Orlando AIA

Write up is merely

Write up is merely interesting..It seems to be biased with the thought of development..

Improve Memory