Maryland officials have announced that a proposal to build a maglev line from Washington to Baltimore has received a commitment for the feasibility study of $2 million from Japanese government. This is in addition to a much larger involvement by the Japanese government, which would include a $5 billion commitment from the government Japan Bank for International Cooperation. The private Central Japan Railway Company has also agreed to waive any licensing fees for using its maglev technology.

The loan would finance one-half of the “somewhat north of “$10 billion cost, as characterized by Northeast Maglev, the developer of the proposed system.

Surely that is a far better alternative than digging deeper into U.S. taxpayer pockets if combined with sufficient private investment. Otherwise any such system could require huge federal grants, or low interest loans through the Federal Railroad Administration Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement (RRIF) loan guarantee program. An RRIF loan could potentially expose taxpayers to a 100% loss, should the maglev system fail to pay for its capital and operating costs, as occurred with what the Washington Post characterized as the “Solyndra Scandal,” which cost taxpayers more than half a billion dollars due to a federal loan guarantee.

The history of private investment in high speed rail around the world is considerably less than encouraging in this regard.

What is Maglev?

Maglev is magnetic levitation, a process by which magnetic forces are used to elevate and propel trains, without friction, at very high speed. The technology has long been favored by futurists and some transport professionals, but there is only one high-speed system in operation (Shanghai). That line has only been partially completed and the rest of the line has been suspended.

“North of” Cost Estimates

The evidence seems to be that the costs of maglev are “north of” high speed rail costs. This is of particular concern for taxpayers, since only two high speed rail lines of the many built in the world have “broken even.” There are recent reports that a third, Shanghai to Beijing is now making a profit Generally large rail project costs have been notoriously underestimated, as the Oxford University work led by Professor Bent Flyvbjerg has shown.

As a result, there is always the risk that a venture proposed as commercial could run out of money during the construction phase, or generate insufficient revenues to its operating and capital costs. In either case, government subsidies would likely be sought by the operator.

“North of” cost projections, such as suggested by Northeast Maglev, seem to be the rule in high speed rail, given that original cost projections for similar projects have been so routinely unreliable.

The current $10 billion estimate for the Washington to Baltimore line is already well north of an earlier $8 billion estimate.

The currently under construction Tokyo to Nagoya and later Osaka (Chuo Shinkansen maglev) has a construction cost in excess of ¥9 trillion (approximately $90 million). With 90 percent of the Tokyo to Nagoya section underground or in tunnels, cost escalation seems likely.

Similarly, the cost of the California high-speed rail line, in its original full he high-speed configuration from Los Angeles San Francisco tripled (inflation adjusted) to well “north of” its 1999 cost projection made. Officials cut the system back from full high-speed rail operation in the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas to reduce costs to a more politically acceptable level.

High Speed Maglev: The One Partial Line

Currently, the only partial high-speed maglev line in the world takes passengers only two-thirds of the way from its Pudong International Airport terminus to central Shanghai.

It was planned to extend the Shanghai maglev line to the center and eventually to Hangzhou, an urban area of 7.6 million residents approximately 180 kilometers (110 miles) to the southwest. However, those extensions have been suspended and high-speed rail service is now available to Hangzhou.

The developers of the Shanghai maglev hoped that China would adopt the technology for its high-speed intercity rail system. China, however, opted for conventional high-speed rail technology and will soon be operating at speeds of up to 350 kilometers per hour (220 miles per hour), the fastest in the world. The train sets are already operating in Manchuria.

A Real Head Scratcher

Significantly, the long and disappointing startup pains of maglev may be coming to an end.

The Central Japan Railway has begun building the Tokyo to Nagoya and eventually Osaka Chuo Shinkansen maglev line. The currently planned completion date for the Nagoya section is 2027, with a package of financial incentives worth and a ¥3 trillion loan from the Japanese government intended to advance the completion date for the new going to Osaka section from 2045 to 2037. Thus, Japanese taxpayers are already potentially “on the hook” financially.

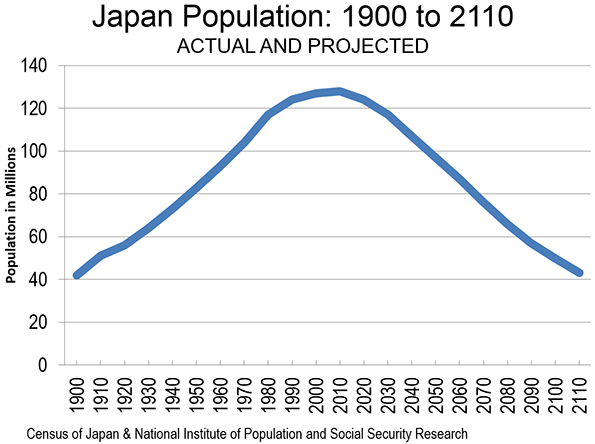

There’s an element of the bizarre here. How much additional transport infrastructure is required in the nation that is losing population at a faster rate than anywhere else in the world? By the earliest date the Osaka extension opens (2037), Japan’s population will have fallen 14 million (more than 10 percent) from today, according to projections of the National Institute for Population and Social Security Research. A quarter of a century later (2062), the population will have dropped another 27 million, to 85 million. That is 10 million fewer people than the 95 million who lived in Japan when the first high speed rail line opened just before the 1964 Olympics. In 2089, Japan is projected to have only 58 million people, fewer than almost 170 years (Figure).

One economic development report noted that the line would “help alleviate the population overcrowding concentration in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Yet, by 2110, the entire country is projected to have not many more people than the Tokyo metropolitan region today.

The Chuo Shinkansen maglev is a part of Prime Minister Abe’s financial stimulus program, which has both supporters and critics. The government talks of the economic development the line will induce. Others, such as Edwin Merner of Atlantis Investment Research called the maglev line a misallocation of resources and that passenger demand will be limited.

The line has also been justified as a means to promote tourism. Yet, the average tourist may find the scenery --- much of it very appealing --- from the above ground 1 hour 40 minute ride to Nagoya or the 2 hour 30 minute to Osaka on the conventional high speed rail line more satisfying (such as Mount Fuji) than the hundreds of miles of tunnel on the faster maglev line (Photo).

By Alpsdake (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Protecting US and Northeastern Taxpayers

But, back to the Washington to Baltimore maglev line. A privately financed and commercially viable maglev line would improve transportation in both the Washington to Baltimore corridor and the extension to New York. However, taxpayers need guarantees to ensure that they are not left “holding the bag.”

For example, before any permits for proceeding are issued, the investors should be required to post a bond to ensure that the private funding will be sufficient to complete the system, thus avoiding public subsidy. Further, a performance bond should guarantee that no operating subsidies are required for at least a minimum number of years (perhaps 10 or 25).

A Chance for Success?

With sufficient taxpayer safeguards, there may be a chance for it to succeed. And surely, we wish Japan, the Japan Bank for International Development, the Central of Japan Railway and Northeast Maglev the best, hoping that they can provide a fully commercial venture. On the other hand, like Ford’s “Nucleon” nuclear powered automobile (proposed in the 1950s), the time for maglev may never come.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Lead photo: Chuo Shinkansen maglev by Saruno Hirobano - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30917648