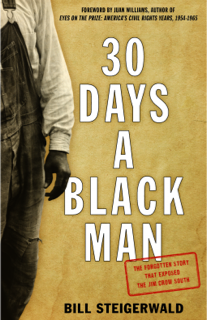

The following is adapted from Bill Steigerwald’s new book 30 Days a Black Man: The Forgotten Story That Exposed the Jim Crow South. The book traces a forgotten but important 1948 undercover journalism mission into the Jim Crow South by a star Pittsburgh Post-Gazette newsman.

Ray Sprigle, a Pulitzer Prize winner, disguised himself as a black man and spent a month seeing what life was like for the ten million African Americans living under America’s oppressive and humiliating system of apartheid.

Sprigle’s nationally syndicated newspaper series about his experiences – and his passionate outrage at the un-American inequities he saw – shocked the white readers of the North, outraged the segregationist white newspaper editors of the South, pleased millions of black Americans and started the first debate in the national media about the future of legal segregation.

Steigerwald’s book, available on Amazon, includes a snapshot of Pittsburgh’s vibrant Hill District, the integrated urban black working-class neighborhood nicknamed “Little Harlem” and made famous by the plays of August Wilson. Below is an excerpt from the book Kirkus Reviews calls a “rollicking, haunting American history".

Pittsburgh in White and Black

Pittsburgh was feeling pretty good about itself in the fall of 1947. The capital city of what Franklin Roosevelt called “The Great Arsenal of Democracy” was still basking in the glory of supplying most of the steel America needed to win World War II. Its population was about to hit its all-time peak of 676,000. It was the twelfth largest city in the USA and the busy hub of a productive metropolitan area of 2.6 million. It was true that it was noisy, shockingly dirty, ugly, dense with people, clogged with traffic, polluted with industrial wastes, and pocked with hard urban poverty. But it had enormous corporate and private wealth, top-flight universities, and major-league culture and sports.

Pittsburgh’s metropolitan population was 90 percent non-Latino white, predominantly Catholic, and heavily Democratic – and remains virtually the same today. Its huge blue-collar workforce was religiously pro-union. Inside Pittsburgh’s crowded city limits were a dozen middle-class urban neighborhoods, thousands of fine homes, and many mansions. There were also scores of ethnic working-class neighborhoods built on the sides of cliffs, on the top of hills, or stretched out in ravines and hollows or along the rivers. There was no single large black ghetto. But about 112,000 blacks, including many recent migrants from the South, lived within the city or nearby in tight neighborhoods in smaller towns throughout Allegheny County.

With the war over, the “Smokey City” had finally started the long-overdue process of cleaning up its air. The average Pittsburgher had no reason to think their city was headed anywhere but up, and yet beneath the permanent fog of smoke and steam its sprawling four-hundred-acre steel mills were sliding toward obsolescence. Over the next three decades, metropolitan Pittsburgh would be forced to de-industrialize by national and global economic forces beyond its control. Its mighty steel industry would collapse. It would hemorrhage population, become the unofficial capital of the Rust Belt and then slowly recover by diversifying its stagnant economy, so that health care, education, and government became its chief job providers. But in the fall of 1947 it was still a prosperous industrial city living of its glorious past, a place where hourly wages of nearly two dollars and generous benefit packages made the region’s union steelworkers the highest paid blue-collar workers in the world.

To say the city’s largely unskilled black workforce was not sharing equally in the industrial bonanza of Pittsburgh is an understatement…. Job opportunities for blacks in the North were far better than in the Jim Crow South, yet they were far from equal. In both public and private employment, black men and women in Pittsburgh were rarely able to get good blue-collar jobs and seldom able to advance if they got one. They were hired last, red first, and invariably paid less. There was a distinct color line in Pittsburgh’s steel and construction industries. About 40 percent of the area’s employers, including some of the largest, barred black employees outright. The unions that controlled the best industrial jobs were virtually lily-white and intent on staying that way. Meanwhile, white-collar jobs for black men were virtually nonexistent in business, finance, real estate, education, and medicine.

Legal segregation in housing didn’t exist in Pittsburgh, but its urban and suburban neighborhoods were nevertheless segregated. As in other northern cities, real estate agents and private housing developers wrote restrictive covenants into the contracts of white homebuyers that prohibited the resale of their homes to someone of a different race. As Richard Rothstein documents in his best-seller, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of how our Government Segregated America,” federal housing policy enforced segregation by requiring builders to include restrictive covenants in their new developments. White landlords kept their apartment buildings segregated. Less subtly, real estate agents simply would never show a black couple a house for sale in a white suburb.

Other common but no less degrading varieties of Jim Crow–like private discrimination existed throughout Pittsburgh. Black shoppers couldn’t try on clothes in downtown department stores. Black baseball fans had to sit in certain sections of Forbes Field, where the Pittsburgh Pirates played. Black kids were expected to swim only in the city’s traditionally all-black public swimming pools, and as late as 1945 blacks had to sit in the balcony at neighborhood movie theaters. The best hotels in the city refused black guests no matter how famous, which is why Jackie Robinson, Paul Robeson, Louis Armstrong, and other notable visitors regularly had to stay in the Hill District, the city’s largest and most important black neighborhood.

The Hill District occupied the high ground in the center of Pittsburgh, but it was the city’s most depressed neighborhood. Nicknamed “Little Harlem” for its nationally famous jazz scene and jumping nightlife, it was a predominately poor but vibrant urban neighborhood of about forty thousand blacks and ten thousand whites. The Hill’s disorderly maze of residential streets, business districts, rundown apartments, and junked-up alleys looked over at the stumpy skyline of downtown from a steep but walkable slope. The area was originally settled by immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and Eastern Europe… By the late 1940s the Hill District contained the largest concentration of blacks in metropolitan Pittsburgh. It was also home to two dozen nationalities, including Italians, Russian Jews, Greeks, Eastern Europeans, and Syrians.

An unregulated, loosely policed city within the city, the Hill’s bustling, self-sustaining, partially subterranean economy provided virtually everything its human melting pot needed. Its schools, shopping districts, nightclubs, gambling dens, and whorehouses were integrated. Blacks owned and operated hotels, bars, movie theaters, restaurants, groceries, drugstores, clothing stores, photography studios, florists, bookstores, funeral homes, and social clubs. There was a black YMCA. A cheap, efficient but illegal system of unlicensed cabs called “jitneys,” which still thrives in the Age of Uber, took care of the transit needs of everyone from grandmothers to bar hoppers. Rising above the dense human commerce and poverty were the spires and pointed roofs of two dozen churches and several synagogues.

The Hill District was home to the Pittsburgh Courier, the country’s largest and most widely distributed black newspaper. But during the 1930s and 40s, it was more famous around the country for two things— baseball and jazz. The Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, two of the best teams in the history of the professional Negro baseball leagues, were based in the Hill District. Its black community was an incubator of a dozen seminal jazz musicians including Earl “Fatha” Hines, the father of modern jazz piano, and baritone crooner Billy Eckstine, who in 1947 was poised to become white America’s first major black pop singer. Unlike venues downtown or in the suburbs, where blacks were usually excluded or made to use their own dance pavilion, the Hill’s entertainment complex was colorblind. Its integrated clubs and dancehalls were one of the few places in Pittsburgh where blacks and whites constantly socialized.

Despite its energy and glamour, however, by 1947 Little Harlem was in terrible socioeconomic shape. The Lower Hill, where sixty-four hundred black and sixteen hundred white people lived, rented, worked, went to school, and worshipped, was particularly distressed. You could buy everything from refrigerators and Italian ice to marijuana, kosher hot dogs, and live chickens on its teeming streets. Violence was rare. The sidewalks were generally safe for kids, women, old folks, preachers, numbers runners, or a friendly game of craps. Men played checkers outside late into the night and people slept on fire escapes in the summer, but there was nothing romantic about its ratty urban poverty.

The Lower Hill’s rough apartments and tenements were overcrowded, rundown, dirty from years of smoke and soot. Part of it was a classic urban slum. Communal faucets in the hallways and outdoor privies were common and private bathrooms were rare. Decades of malign neglect by city hall had made things worse. Streets—many not paved—were maintained poorly at best. Police and re protection, as well as health and sanitation services, was inadequate. Making matters worse, many of the Hill District’s middle-class blacks and professionals had moved to better black city neighborhoods. Most of the blacks left behind were poor or lower-middle working class. They were maids, garbage men, waitresses, bartenders, musicians, jitney drivers, and small-time criminals.

For most of Pittsburgh’s older, squarer, law-abiding white population, Little Harlem was an unknown and scary place they’d never dare to go. Along with the great jazz scene, it was where poverty, vice, violence, and black people dwelled. The city’s three daily newspapers—the Press, the Post-Gazette, and Sun-Telegraph—rarely mentioned the Hill or its “colored” residents. They The all-white papers didn’t care about the Hill District’s present or its future. In 1947 city hall was quietly making plans to raze and redevelop Pittsburgh’s worst slums, which meant bulldozers and wrecking balls were coming for the unsuspecting people living in the city’s poor and politically defenseless neighborhoods. The Hill was the planners’ first target and the white newspapers were enthusiastic propagandists and cheerleaders in the brutal crusade for civic progress and urban renewal.

To the square white men who made the important decisions in town—the entrenched Democratic Party machine, zillionaire businessman Richard King Mellon, and a handful of lesser Republican corporate honchos, boosters, and newspapermen—the Hill was not hip or culturally exciting. It was not a self-reliant community of hustling people, black and white, who needed to be given a helping hand by government or have their lives improved with new jobs or better housing. It was a cancerous slum that threatened the future growth, health, and beauty of their cosmetically challenged city. Pittsburgh’s powerbrokers had plans for a new cultural center for rich white people like themselves and a dozen identical upscale apartment towers. Within a decade a hundred acres of the Lower Hill would be clear-cut to the sidewalks and thousands of people who called it home, most of them poor and black, would be gone without a trace.

Bill Steigerwald worked for the LA Times in the 1980s, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in the 1990s and the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review in the 2000s. He lives south of Pittsburgh and is a part-time Uber driver while he prays for Hollywood to turn 30 Days a Black Man into a movie.