With both metro and rural areas projected to face a labor force slowdown by 2025 as more baby boomers exit the workforce than millennials enter, where millennials chose to live and work becomes increasingly important. In this report, Chet Bodin, a labor market analyst for Minnesota's Department of Employment and Economic Development, details how the migration patterns of millennials will impact Minnesota's regional labor markets.

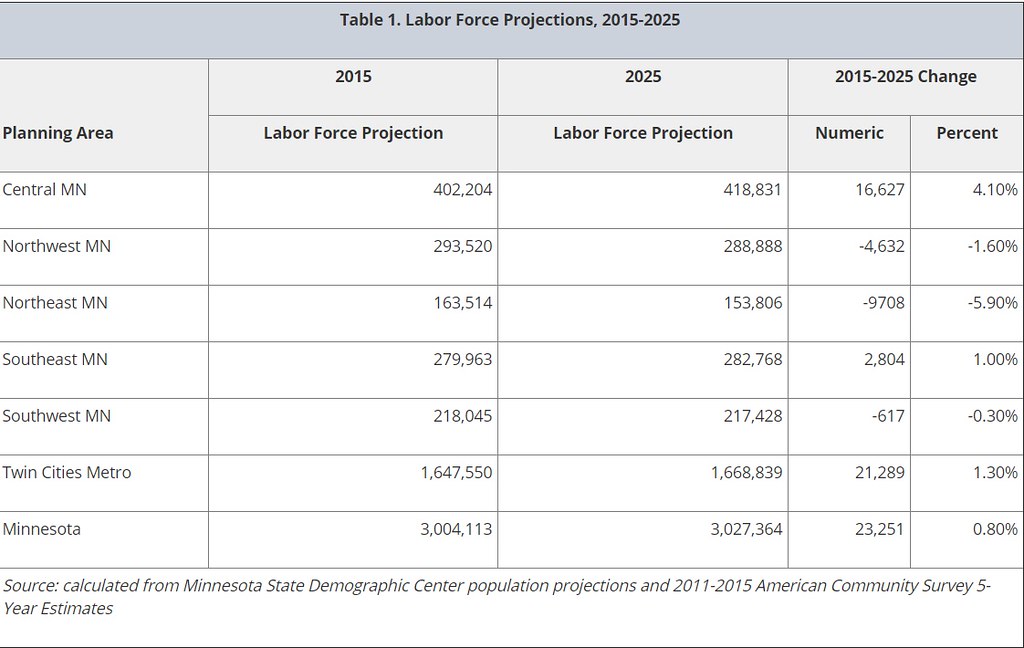

Discussion surrounding the millennial generation is widespread and multi-faceted, largely because it is soon to account for the highest percent of Minnesota’s workforce in the next decade. But what makes millennial impact even more important to employers, policymakers, and educational institutions is the context of their arrival. Even as millennials enter the labor force in droves, the previous generation to dominate the workforce, the baby boomers, exit even faster. Consequently, not only are values and norms in the workplace changing, but the ensuing workforce shortage has created a simultaneous challenge. By 2025 both metro and rural areas alike will be facing at best a plateau in labor force growth like never before (see Table 1). Many areas will see their labor forces shrink. The ability of local employers to withstand a shortage will depend on where millennials choose to plant their roots, and the extent that communities prioritize their livelihood.

In Minnesota the supply of millennial workers varies by region, and whether an employer is looking to attract more or live without them, their relative size in the workforce and patterns of mobility matter. The sizable demographic shifts underway have employers of all shapes and sizes examining generational context in their management and hiring strategies more and more.

However, generational identity is often based more on social acceptance than definite timelines, and the specific boundaries of the millennial generation remain somewhat unsettled. If for no other reason, demographic starting and ending points need to be established to provide macro-level quantitative analysis. Most efforts to pin down the boundaries of the millennial generation range between 1977 and 2002, but both the floor and ceiling vary.

The generational boundaries for this analysis are set parallel to the data sources utilized. In 2015 estimates from the American Community Survey (ACS), millennials would have been between the ages of 13 and 38 at the widest range. ACS population estimates, however, are organized by five-year age groups (i.e., 0-4 years, 5-9 years, etc.), and trend analysis benefits from age ranges that follow suit. The youngest age limit can easily be increased to 15 since most people do not enter the workforce until at least that age anyway. In addition, most estimates of the millennial generation do not exceed 20 years in length, which would put the upper age limit at 34 years of age in 2015. By that estimation, millennials researched here would have been born from 1981 to 2000.

Regional Differences

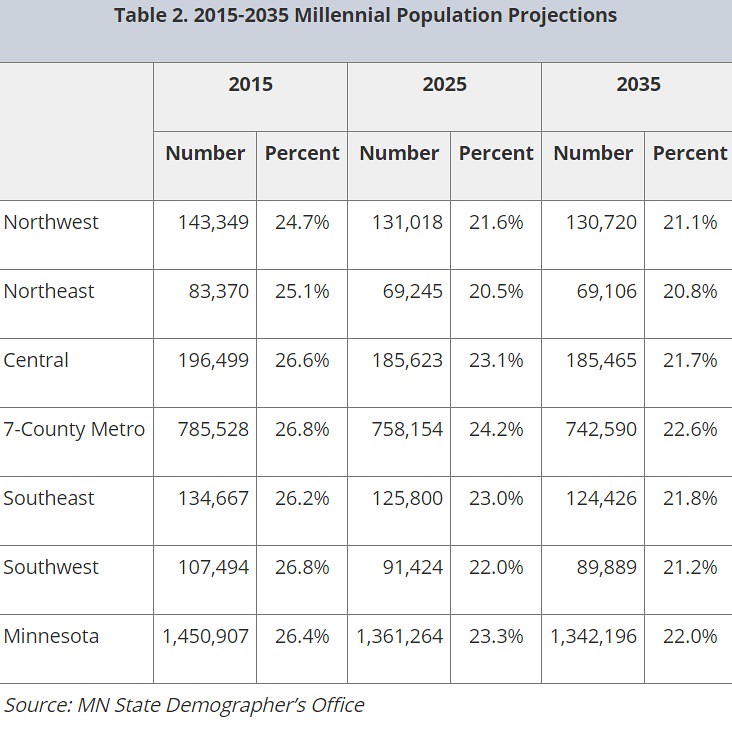

Based on this, the millennial generation – people between 15 and 34 years of age in 2015 – accounted for more than a quarter of Minnesota’s statewide population. As they come of age, millennials will have a significant impact on Minnesota’s culture, economic demands, and workforce supply.

However, the extent of millennial influence varies by region and will continue to change over time. Population projections from the Minnesota State Demographer’s Office estimate that millennials will hold a shrinking share of the state’s population over the next two decades. Twenty-somethings often migrate away from their hometowns for other opportunities, particularly young adults who originate from rural areas.

In Greater Minnesota the Southwest region is projected to have the most millennial out-migration from 2015-2035 and the fastest population decline overall (see Table 2). Yet, their to-be-determined migration patterns may be the contributing factor to actual future outcomes, as many millennials are still in high school and have yet to decide whether they will leave their home towns.

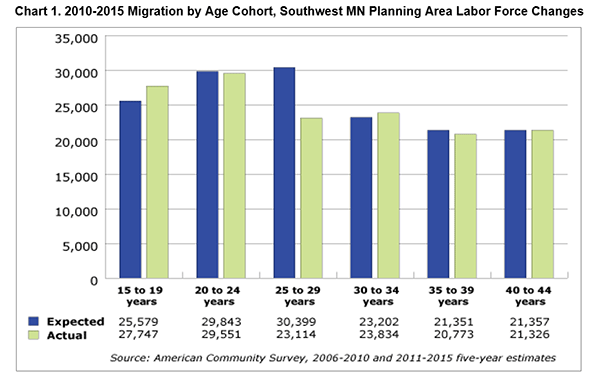

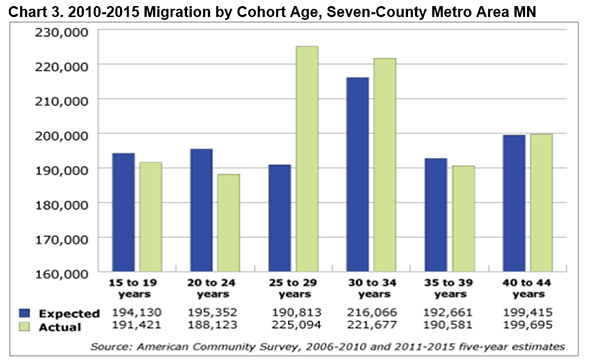

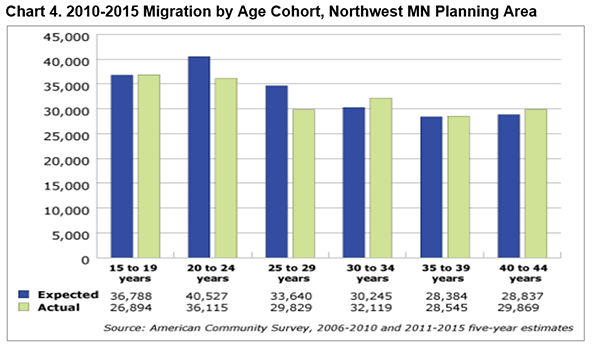

A Simplified Cohort Analysis helps demonstrate how migration patterns by age groups impact population makeup over time. For example, those who were in the 15 to 19 year old age group in 2010 will be in the 20 to 24 group in 2015. If no one moves in and no one moves out, the count of people 15 to 19 in 2010 would provide an “Expected” count (or control number) of people 20 to 24 in 2015. However, “Actual” numbers are oftentimes different, showing in- or out-migration.

In Southwest Minnesota, a large portion of the millennial generation aged into their 20s from 2010 to 2015, and over 7,500 more of these 20-somethings vacated the region than moved in (see Chart 1). The population projections in Table 1 indicate millennial out-migration will continue as those who are teenagers now enter their twenties and begin to test other markets from 2015-2025.

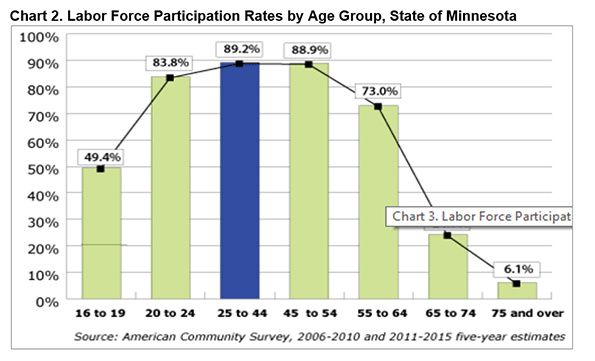

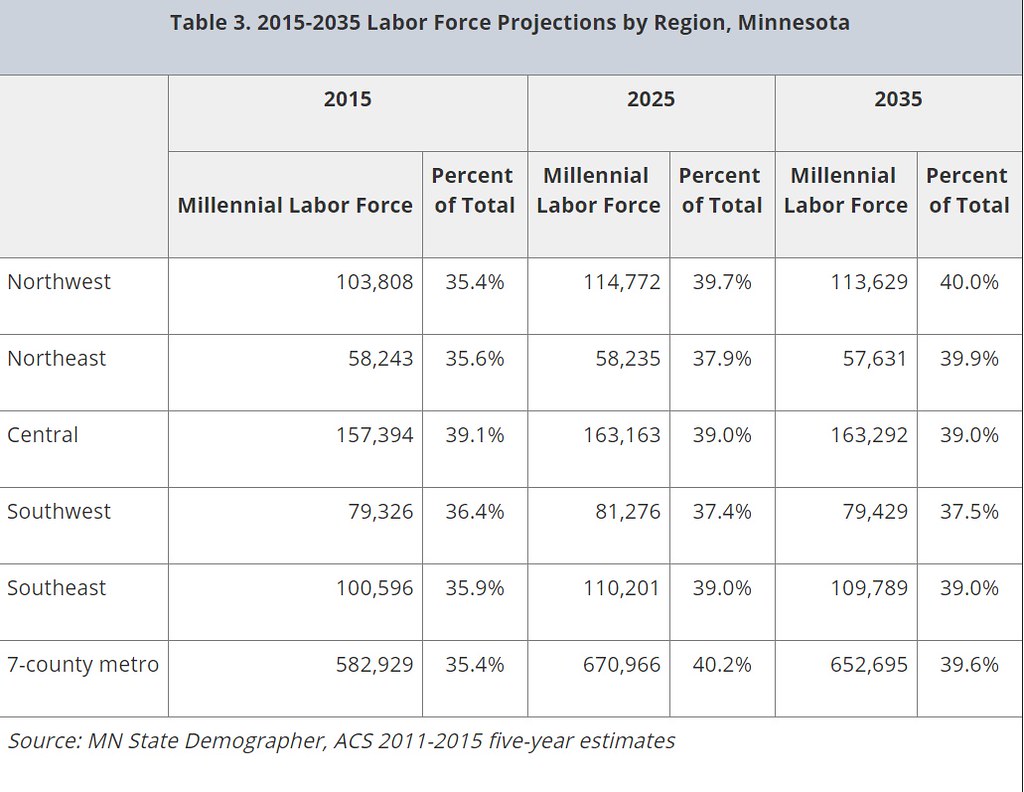

While the number of millennials in Greater Minnesota will likely decline in the next decade, their impact in the regional workforce will increase in most regions. Based on the labor force participation rates of different age groups, millennials throughout Minnesota are likely to have a larger role when the entire generation comes of age. Historically, the highest labor force participation rates are among those 25 to 44 years of age – the approximate age of all millennials in Minnesota by 2025. (See Chart 2).

But like migration patterns, labor force participation rates vary by region. For example, teenagers tend to have higher labor force participation rates in Greater Minnesota than in the seven-county Metro Area. The number of millennials in a regional labor force varies by their population size and participation rate, but the proportion of the labor force they fill also depends on the activity of other age groups. In Northeast Minnesota the labor force participation rate of those 25 to 44 years of age was nearly 24 percent higher than those 54 to 65. Naturally then, the proportion of millennials in the regional workforce will grow, even as their numbers decrease overall. Indeed, the proportion of millennials in the Northeast labor force is projected to grow by over 4 percent by 2035. (See Table 3).

The percent of millennials is projected to increase in almost every regional labor force of nearly every region of Minnesota by 2025. The only exception, Central Minnesota, currently has the highest percentage of millennials in its workforce, and despite a slight decrease in the proportion of millennials projected there in 2025, the number of working millennials looks as if it will to increase by more than 5,000 in that time.

The labor force in the seven-county Metro Area is set to have the largest infusion of millennials workers over the next 10 years. Close to 90,000 more millennial workers are projected to inhabit the metro by 2025, the result of heavy metro-migration by those in their late 20s (see Chart 3). From 2010-2015 there were 18 percent more 25-29 years olds than expected, trending in stark contrast with the migration patterns of 25 to 29 years olds in every other region of the state. By 2025 the youngest millennials will fall into this age category.

The migration patterns of the oldest millennials, who will be in their early forties by 2025, will also have significant effects on the composition of regional labor markets. To varying degrees, every region of the state attracts more people ages 30 to 34 than they lose, but the same cannot be said about age groups 35 to 39 and 40 to 44. From 2010-2015 Northwest Minnesota was the only region to attract more people from both of these age groups than it lost. (See Chart 4).

Therefore, based on current trends, millennials in Northwest Minnesota are projected to account for almost 40 percent of the regional labor force by 2025 (see Table 3).

What may be equally important to future migration patterns, however, is the qualitative nature of the millennial generation in the workplace, and whether parts of Greater Minnesota have the cultural flexibility to accommodate the new economic and technological norms millennials practice. After all, most migration to Greater Minnesota generates from the metro area, and millennials may not be as eager to move in their 30s and 40s as others are today. Fortunately, employers throughout Minnesota still have time to prepare for possible changes or even influence labor force trends. Cultural differences notwithstanding, the potential for a labor force shortage in the near future has employers looking to maximize their talent and attract workers. Employers who chooses not to upgrade their technological capabilities or stay competitive with their wages will have a hard time accomplishing either. But just as important may be the influence industry leaders have on local culture – creating communities that millennials are excited to be a part of can have a major impact. As the numbers indicate, there will be real opportunities to generate mobility to rural parts of Minnesota over the next 10-20 years.

Chet Bodin is DEED's regional labor market analyst in northwestern Minnesota. He has a bachelor's degree from the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul and a master's degree in public policy from the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota.

Photo: Telepwn at English Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons