Over the past three years, the nation’s largest transit systems have endured a broad and unprecedented ridership decline. By far the largest drop has been in Los Angeles and this has resulted in justifiable consternation.

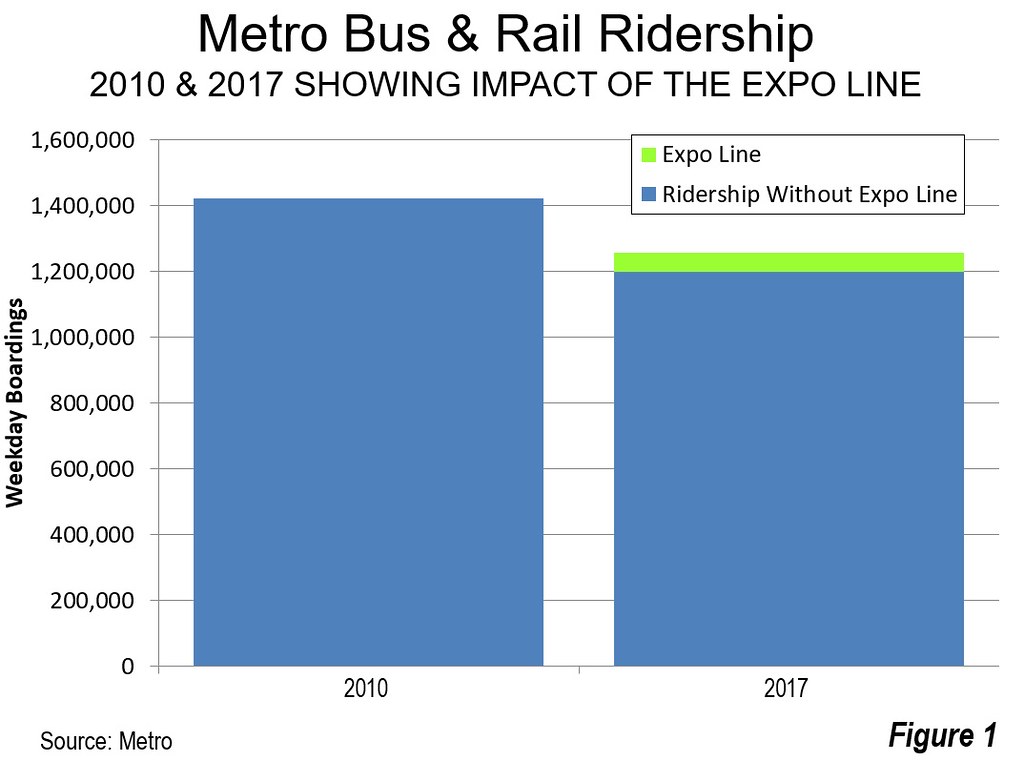

Metro, the largest transit system in Los Angeles County, has seen its passenger counts (boardings, see Note 1) drop from over 1.5 million each weekday in its recent 2013 peak, to just over 1.25 million in 2017. This decline has occurred at the same time as Metro’s third most successful new rail line, the Expo line, from Santa Monica to downtown Los Angeles, was opened. Figure 1 shows 2010 and 2017 ridership and indicates that for each Expo line passenger, there was a loss of three passengers in the rest of the Metro system.

This is occurring as Metro has undertaken one of the most significant rail and busway building programs in modern US history. Now six rail lines and two busways head to different destinations from downtown, complemented by one lateral line (the Green Line) and one busway (the Orange Line). Yet, despite expenditures of over $15 billion on the already opened rail and busway lines, ridership has never been restored to its 1985 bus only peak.

Responses to the Metro Ridership Collapse

There have been differing responses to the continuing decline. Some --- in the face of dismal numbers --- anticipate a future of greater transit ridership and less car use. For example:

Larry Wilson, a member of the Southern California News Group editorial board (which includes such outlets as the Orange County Register, the Los Angeles Daily News, the San Gabriel Valley Tribune and the Pasadena Star-News) recently suggested that increasing traffic congestion will drive higher ridership. He concludes that “Transit ridership will come back, once the system connects more dots.”

Los Angeles Times columnist Liam Dillon expresses concern that the state is falling far short of progress toward the mobility transformation considered necessary by the California Air Resources Board. This would require “four times” more frequent travel by walking, a “nine-fold” increase in bicycling” and a “substantial boost in bus and rail ridership.” After decades of trying to entice drivers to walk, cycle and jump on transit, with virtually no success, this “necessity” is not likely to be achieved without compulsion. Nor has it anywhere else in the world.

Others suggest that the ridership losses are driven by structural factors.

Substantial coverage was given to a recent report produced for the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG), the local metropolitan planning organization (MPO). The U.C.L.A. authors, Michael Manville, Brian D. Taylor and Evelyn Blumenberg note that: “Areas that were heavily populated with transit commuters in the year 2000 became, in the next 15 years, slightly less poor, and significantly less foreign born. Perhaps most important, the share of households without vehicles in these neighborhoods fell notably. All these factors align with a narrative where a transit-using populace is replaced by people who are more likely to drive.”

They also note the benefits to lower income households who obtain cars: “When lower-income people graduate from transit to driving, transit agencies bear a cost, but the other side of that cost is a large benefit for both the people who start driving and for society overall.” This is a refreshing rebuttal to the academic dogma that often sees the purpose of cities in terms of “place-making,” or transit, rather than people, a distortion roundly criticized by economists at the London School of Economics.

This trend could augur more transit losses for Los Angeles. Low-income households seem likely to continue buying cars because of the mobility options they offer, not the least of which is that 60 times (not 60 percent, but 6,000 percent) as many jobs can be reached in 30 minutes by car than by transit by the average Los Angeles commuter, according to measures published by University of Minnesota researchers. Their data also shows that drivers can reach more than 150 times as many jobs by driving as by walking.

Another theory, strikingly consistent with the UCLA observations, is advanced by Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal of the Los Angeles Tenants Union, in a Los Angeles Times op-ed entitled: “Transit-oriented development? More like transit rider displacement.” Ms. Rosenthal cites data showing that “…L.A.'s transit riders are mostly low-income black and Latinos: 88% of Metro bus riders are people of color, and more than 50% have annual family incomes under $15,000. When they lose housing near bus or rail lines, they lose access to transit.” Her point is that the transit-oriented development that occurs along rail lines displaces transit riders, who cannot afford higher rents.

Metro’s aggressive rail building program may thus, albeit unintentionally, be contributing to the ridership losses, as the increasing number of affluent riders are far less than the number of lower income transit riders who are being driven farther away from transit. I am confident that none of us serving on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission at the creation of the modern rail system expected it to lead to lower ridership (Note 1).

Even the Proponents Projections do not Support the Narrative

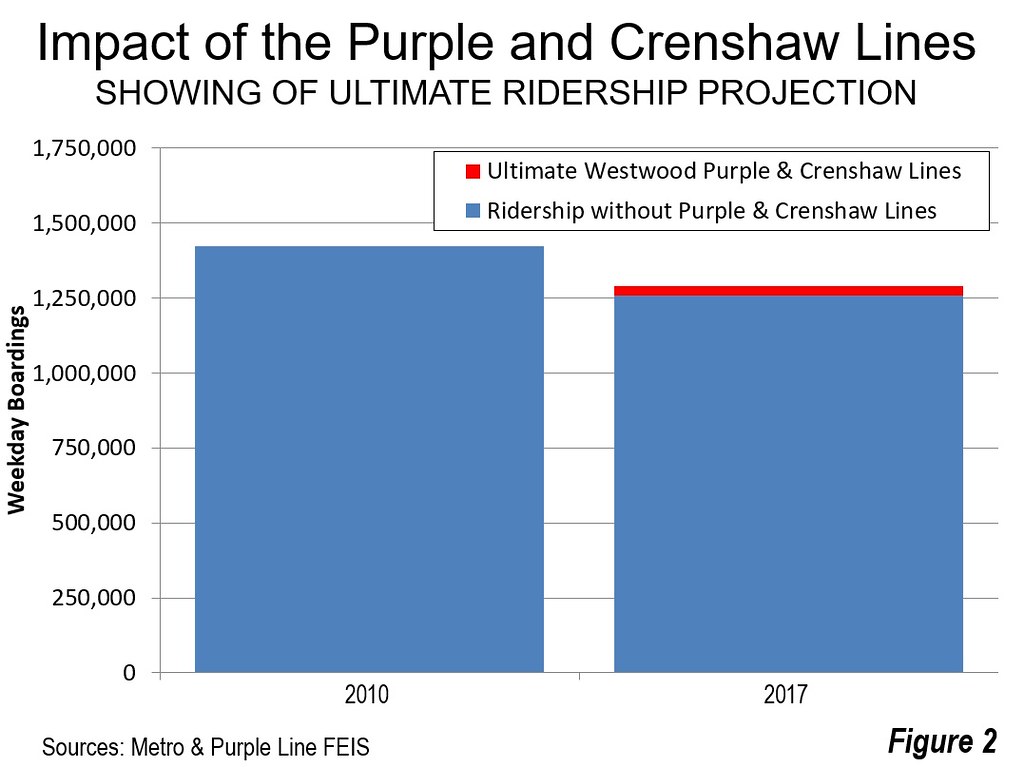

Meanwhile, hopes for greater transit ridership hinge on the new rail lines, like the Purple Line extension to Westwood and the Crenshaw line. These, however, are vain hopes, because not even the transit planners project meaningful transit ridership increases. In the long run (2030 for the Crenshaw line and 2035 for the Purple line), official projections indicate not many more than 30,000 additional riders on a daily basis. Figure 2 illustrates the 2010 ridership level, and the lower 2017 level, with the additional ridership projected for the Purple and Crenshaw lines.

These 30,000 new riders should be compared to the 18,000,000 million new daily trips that are anticipated in the region by 2030. The 30,000 is not even sufficient to retain transit’s share. For example, the Crenshaw line planning documents indicate that transit accounted for 2.3 percent of regional trips. The very same planning document predicts a market share reduction by 2030 with the addition of the Crenshaw line. Even adding the projected Purple line riders, the share of trips by transit would drop to 2.0 percent, a reduction of 14 percent.

Utopian Fantasy: Connecting the Dots by Transit

No vision of a Los Angeles with meaningfully and proportionally less automobile use is rational (or for that matter would it be in any other modern urban area, but that is a different article). There is simply not enough money for transit to connect enough “dots.” Professor Jean-Claude Ziv and I found that to “connect” the geographical “dots” (equal the connectivity of the automobile) with rapid transit would require from half to three-quarters world megacity gross domestic products, each year, in a paper presented to the World Conference on Transport Research Society (WCTRS) in 2007. Of course, some dots can be effectively connected, like to the largest downtowns (central business districts), by far the easiest to serve tend to average around 10 percent of employment, though much less in highly decentralized Los Angeles. But that is a far cry from an automobile competitive regional transit system.

The reality is that the millions of Los Angeles households could not retain their standard of living if they rode transit, much less walked or cycled. Many more would be in poverty. People will choose transit (and walking and cycling) only if the travel times and geographical coverage are competitive with driving. Moreover, there is no point in delusions about radical land use transformations, especially where governments require the consent of the governed. In short, there is no roadmap to any transit utopia connecting sufficient dots, because none are feasible.

Note 1: US transit agencies count passenger “boardings,” which is the number of times a passenger enters a vehicle to travel from their origin to the destination. Thus, a passenger whose trip takes two buses and one train is counted as three.

Note 2: My involvement as a member of the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission is detailed in Transit in Los Angeles.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Los Angeles Blue Line, Long Beach (by author).