Starting in the 1980s, the central Puget Sound region committed itself to a network of four-car light-rail trains having less passenger capacity than the eight-car heavy-rail subway rejected by King County voters in 1968 and 1970, a service territory that included Seattle and Bellevue. The plan back then did not include tracks into Snohomish County to the north and Pierce County to the south. Those two jurisdictions were added to the voter-approved Sound Transit plans beginning in 1996.

Monthly ridership of Seattle’s light rail has increased since the grand opening in 2009, now at two million boardings per month, as shown in the graphic of ridership reported to the U.S. Government. Two new stations north of downtown Seattle are the source of the recent upward surge.

After a half century of regional growth, a question arises: Will there be room enough for likely commuter volumes on the Link four car trains, given the unexpected popularity of the partially built Seattle light rail so far, given population growth, given a TOD (transit oriented development) focus, given the bus-to-rail feeder services being planned, and given hard limits on the physical capacity of the system?

Sound Transit – Seattle’s regional mass transit agency -- has already reported in environmental analyses that the trains will be unable to carry enough commuters to make any difference in peak period congestion on the roads. Instead, light rail is advertised as an alternative to driving in congestion, for those who choose to ride. But what if the trains alongside the busiest stretches of I-5 leading to Seattle downtown are so full that some customers seeking relief are turned away?

How that could happen: The length of train stations limits Sound Transit to four car trains. There is also a limit on how many people fit on a rail car. The planned control system technology and station design put limits on train spacing and frequency.

In the plans made in the 1990s for the rail service going between Lynnwood and downtown Seattle, the trains were expected to carry a maximum of 800 passengers per train, with trains coming every three minutes, translating to 20 trains per hour, or 16,000 customers per hour in one direction.

On the day of the Seahawk Super Bowl victory celebration in February 2014, one of us took a photo of Link in the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel showing what 800 passengers per train looks like with trains coming about every six minutes, timing set by how long it takes to load and unload people from the crowded railcars.

That many passengers mean almost two standees for every seated passenger. In ordinary commuting, passengers bring along handbags, knapsacks, luggage, or an increasing number of bicycles.

During the ST3 campaign for further network expansion, which ramped up in summer 2016 just after the University of Washington extension opened for service, Sound Transit representatives began defining what before 2015 was called “crush” loading as “standard” loading for routine maximum train capacity. But loads with that many standing passengers require unloading and boarding times that may not be possible if trains are coming by every three minutes and necessarily staying only a short while in the station before the next train comes along.

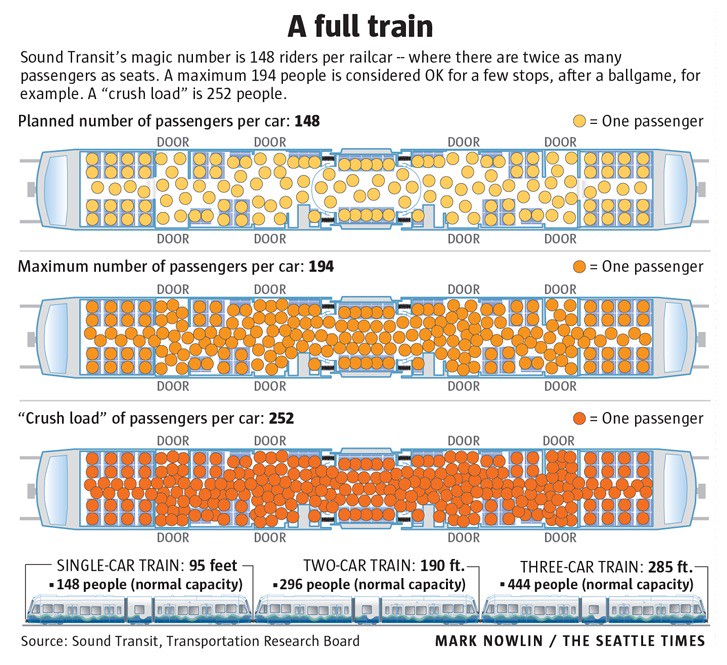

On August 8, 2016 in the report “Sound Transit keeping close eye on crowded light-rail trains” The Seattle Times published diagrams showing what passengers on really full light rail train cars would experience. The dots represent individual passengers.

Today, customers of Sound Transit light rail waiting on station platforms are often seen stepping back from the doors of trains ready to depart when the load reaches around 150 riders per car. This is the crowding seen in the first of the rail car floor plans shown here, whereas the more crowded second picture is now regarded by Sound Transit as an acceptable standard.

Based on observations of operations, we estimate the realistic Link light rail practical operating capacity during daily peak commuting hours is 150 passengers per rail car adding up to 600 passengers per train on 20 trains per hour, equal to 12,000 passengers in one direction during a peak hour. Safely evacuating trains quickly in emergencies is at risk with heavier loads than this. 12,000 per hour capacity is a small number for the single-track-in-peak-direction leading into downtown Seattle through University District and Capitol Hill considering the claim of 50 to 100 future years of life for this rail corridor. After all, additional rail ridership coming from ongoing future densification of residences and offices around every train stop is the approved public policy of the region.

A recent tour along the current light rail corridor reveals that most station areas are not yet built up to the transit-oriented density levels that will be characterized by the planned multi-story apartment buildings to be built close to transit access. More rider demand is coming when that density is built. The Sound Transit plan to build a second tunnel in downtown Seattle does not address peak crowding on single tracks for each direction in and out of the main center city daily destination for most rail commuters.

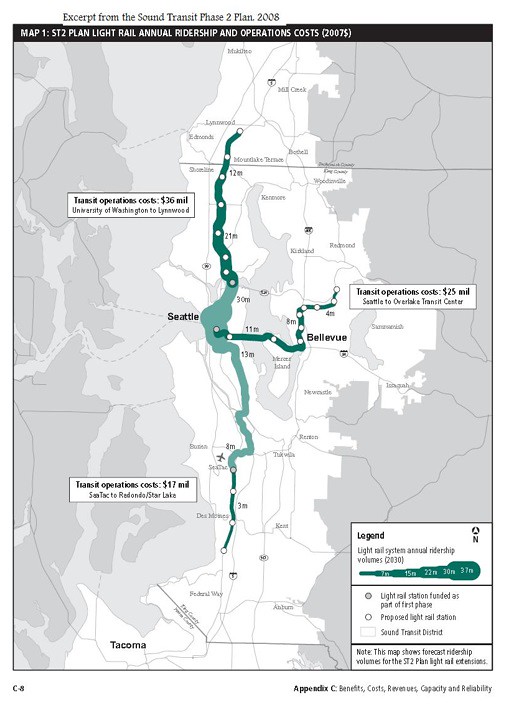

The historical but still valid 2008 Sound Transit planning map shown below illustrates through line thickness where planned ridership comes from out to 2030. The thickness of the line north of central Seattle illustrates that the bulk of future ridership is expected to come from the Northgate and Lynnwood extensions north of Seattle, the line that reaches into Snohomish County that is much desired by political leadership there.

We all now understand that new highway capacity in a growing region is readily grasped by more car commuters, and overwhelmed in just a few years. Won’t this happen on light trail as additional trains are added, filling up with standing passengers, and hitting technology-set load and frequency limitations?

Think about this scenario: Passengers on Link Light Rail in the late 2020s boarding in the morning for downtown Seattle at Lynnwood Park-and-Ride north terminus would get a seat, because the trains start out empty before rolling. Then more passengers are added at each additional station as the train moves southward. Would customers waiting on the platform down the line at Roosevelt Station even find room enough to stand, with five or eventually six stations adding passengers ahead of them? What about reliable capacity for the additional commuters expecting to board the southbound train near their transit-oriented residences on Capitol Hill, the last stop before downtown Seattle?

Many urban planners around Seattle are saying that more housing near outlying light rail stops is a key strategy for achieving greater housing affordability and thus more equitable growth. Light rail capacity along the planned spine between Tacoma and Everett would be further challenged by even more customers getting aboard on the East Link, West Seattle, and Ballard extensions.

In conclusion, are the trains serving the suburbs both north and south from the Seattle CBD – especially north into Snohomish County – going to provide sufficient capacity to support the rail-oriented strategy that generations of urban planners have been counting on since the 1960s? Is “light” rail sufficiently “heavy” for our fast growing metropolis? After reading our analysis presented here Sound Transit staff told us “rider capacity, frequency and rider experience on our system following future Link expansions will be quite comparable to what people experience in other major metropolitan systems.” We don’t quite find this forecast reassuring.

One of us writing this essay is a big supporter of effective rail mass transit, and one of us has been an urban rail skeptic since the 1980s. But together we agree that a reappraisal and verification of the Link Light Rail design – including the train control technology that determines train spacing – is now important before extending a network that is emerging as built too small, showing increasingly as an expensive big city status symbol set to yield a shallow improvement in mobility.

Despite the Federal approval of grant and loan funding for the Lynnwood extension on December 19th, the crowding issue is so serious that the final design of the system features that limit the passenger capacity should be reconsidered before committing to the July 2024 opening of that extension. As an interim step, rail operations will be severely tested in meeting the peak demand in the shorter, close-in segment of the north corridor when the next three stations including the interim terminus at Northgate are opened in 2021. If these operations reveal that the design of this rail line serving University of Washington and downtown Seattle is inadequate for peak demand even before new stations are added, then extending that line further out into the suburbs without capacity improvements would be an infrastructure failure.

John Niles and David Lange are independent professional systems analysts focused on networks of transportation and information.