As we wrote in Steeltown USA: Work and Memory in Youngstown, Youngstown’s story is America’s story, and that city offers a useful case study for anyone trying to imagine American life after the pandemic. No doubt, coronavirus is a natural disaster that is more contagious, widespread, and deadly than the economic disaster of deindustrialization. But the struggles that Youngstown and similar Rust Belt cities faced after the plant closings of the late 1970s offer a stark warning: the economic crash hitting so many Americans now will have long-term costs. Youngstown’s story also makes clear that we can’t rely on private enterprise or individual effort to fix things.

As leaders debate when and how to reopen the American economy, some have warned that the economic crisis will lead to as many deaths as COVID-19. Our research on the social costs of deindustrialization suggests that although this economic displacement is not as lethal as coronavirus, if not adequately addressed, it will indeed cost lives. After deindustrialization left thousands without jobs, heart disease, strokes, and cancer rates increased in places like Youngstown.

So did mental health problems. A lost job doesn’t just mean lost wages, homelessness, or hunger – important as those material realities are. Laid-off workers also lose important networks and routines. For many, losing a job also means losing a sense of purpose and identity. Combine anxiety, isolation, and self-doubt with fear about an uncertain future, and it’s no wonder so many become depressed or seek relief from drugs or alcohol. As Anne Case and Angus Deaton’s by now familiar study of “deaths of despair” has shown, an uptick in alcoholism, addiction, and depression in the early 1980s eventually become an epidemic of disease, overdoses, and suicides.

Youngstown provides a discouraging glimpse of how the economic devastation of COVID-19 could play out for communities as well. Lost jobs reduce tax revenues, so cities struggle to maintain streets, fight crime, and run schools, libraries, and recreation centers. This disrupts the social networks that enable communities to pull together to address problems.

Deteriorating infrastructure, high crime rates, and poor local schools also pose challenges for attracting new business and investments. Residents and local leaders pursue any new opportunity. Localities compete against each other, offering tax abatements in exchange for jobs. Too often, the result is disappointing. Companies hire few locals, and they move on as soon as the tax deals end, feeding a cycle of local desperation.

Americans could, like many in Youngstown, lose faith in government, business, labor, foundations, and even religious institutions. They might also lose faith in themselves. Self-doubt undermined our community, in part because people internalized the blame implied in media stories questioning why people failed to pull themselves up by the proverbial bootstraps, fell victim to phony economic schemes, or weren’t sufficiently entrepreneurial.

Youngstown’s story had political outcomes, too. Political resentment about insufficient government assistance, led local voters to embrace political demagogues like Jim Traficant. A few decades later, frustration over the community’s continuing struggles and false promises from too many candidates made this traditionally-Democratic area into “ground zero” of Trump country. The current crisis might also generate political effects that could last for a very long time.

People often ask us, what is the answer for Youngstown? Our response is sobering: this place will probably never fully recover. It will survive, but it will not likely thrive. Will that be true for the U.S. after COVID-19?

The answer depends on how we respond. First, we must recognize how the economic policies and business practices of the last few decades created the economic precarity that makes today’s crisis so overwhelming. A society in which so many people live on the edge is particularly vulnerable, as we have seen in recent weeks.

Second, we must expand social welfare programs to provide not only basic food, healthcare, and shelter but also mental health resources to help people recover from the multiple losses of this crisis.

Finally, we must insist that relief programs rebuild the economy from the ground up. We can’t count on business to act in the best interests of communities or workers. History tells us they will act in the interest of investors. We must create a more just and sustainable economy, and that means prioritizing the security of all, not the wealth of a few.

If we fail to recognize that we have the responsibility not only to protect each other’s health but also to protect each other from the devastation of economic collapse, then Youngstown’s story will yet again become America’s story.

Sherry Linkon and John Russo are affiliates of the Kalmonovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University and the authors of Steeltown U.S.A.: Work Memory in Youngstown.

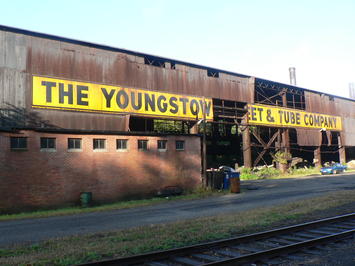

Stu Spivak via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.

Lessons of Youngstown

Sherry Linkon and John Russo are certainly encouraged to express their considered opinions. And so am I. I find their conclusions and prescriptions BUNK; the stuff of socialism pure and simple.