Despite the assertions of some planners and urban boosters, urban core population loss has been the rule since mid-century throughout the metropolitan areas of Western Europe (see note below). For example, the ville de Paris lost a quarter of its population from 1954 to 1999, Copenhagen shrank 39 percent from 1950 to 1991, inner London (This includes the 13 inner boroughs and the “city” of London, which are roughly the former London County Council area) declined by a third from 1951 to 1991 while Milan‘s population declined by a quarter from 1971 to 2001.

At the same time, widely ignored by many American observers, Western Europe has been suburbanizing strongly. Since 1965, virtually all major metropolitan area growth has been in the suburbs. Indeed the share of the metropolitan area population gains in the suburbs has been greater in Western Europe than in the United States.

It is true, however, that there has been a generally modest turnaround in core population trends, with strong turnarounds in the “ancient” losers of Vienna (which peaked in 1911) and inner London (which peaked in 1901). It might be tempting to suggest – as is often done in the United States – that these reversals indicate that Europeans are moving back to the cities from the suburbs.

To answer this question, we examined all of the available “components of population change” reported by the census authorities of Western European nations. Seven of the 17 (the European Union-15 plus Norway and Switzerland) produce such data at a geographical level that makes metropolitan analysis possible. A review of this data suggests that the new residents are largely international migrants and that the core cities generally continue to lose domestic migrants, while the suburban areas continue to perform better with respect to attracting domestic migrants. This parallels the experience in the United States.

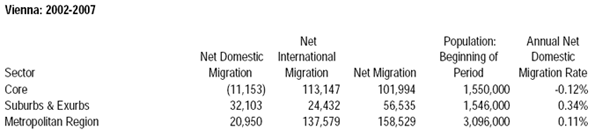

Vienna: Vienna illustrates the trend. The city of Vienna increased its population from 1,550,000 to 1,656,000 between 2002 and 2007. This 7.3 percent gain is impressive but over the same period, a net 11,000 residents left the city. Virtually all of the population increase was the result of international migration, which accounted for 113,000 new residents. On the other hand, the suburbs of Vienna added 32,000 new domestic migrants and also added 23,000 international migrants. Vienna’s population turnaround can be fully attributed to immigration.

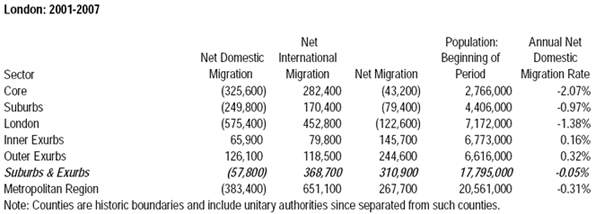

Inner London and England: Like Vienna, inner London’s gains have not been the result of people moving from the suburbs to the city. Between 2001 and 2007, a net 326,000 people moved from inner London to other parts of England and Wales. The domestic migration losses were even larger than the gain of 282,000 from international migration. The inner suburbs (the outer boroughs added to the city in the 1960s) also lost domestic migrants, but at a rate half that of inner London. The exurbs (the two rings of counties outside the Green Belt) added 126,000 domestic migrants and a somewhat larger number of international migrants.

Overall, the London metropolitan region experienced a net domestic migration loss of more than 383,000 between 2001 and 2007. However, there were strong international migration gains, in every sector of the metropolitan area.

Thus, the data indicates that the recent inner London population growth is not the result of suburbanites moving to the city. Inner London’s population growth is being driven by international migration and the natural increase in population (births minus deaths).

As with inner London, the cores of Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle and Leeds-Bradford all lost domestic migrants from 2001 to 2007. Thus, despite the improved population performance of the largest metropolitan areas in the United Kingdom, people continue to move out of the cores, while people are generally moving to suburban areas.

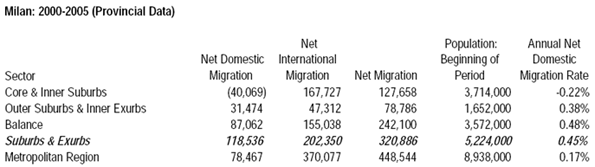

Milan and Italy: The city of Milan, the core of Italy’s largest metropolitan area, has experienced one of Western Europe’s most significant population losses since the early 1970s. Yet, in the early years of the decade, Milan has experienced a turnaround, as the population has begun to grow. The pattern was much the same as seen in London, with a net 40,000 residents leaving Milan province to move to other parts of Italy. At the same time, there was a strong net international migration gain of 168,000. Suburban areas, on the other hand, attracted a net 119,000 domestic migrants as well as a strong component of international migration.

A shorter data series is available for cities (communes) and shows net domestic migration losses in the central cities of Milan, Rome, Naples, Turin, Genoa, Palermo, Florence and Bologna. The suburbs, however, gained domestic migrants, with the exception of Naples. However, the Naples suburban losses were at a far lower rate than that of the city.

It is thus evident that the core areas of the largest Italian metropolitan areas are not receiving net migration from their suburbs.

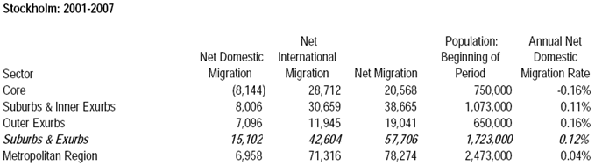

Stockholm and Sweden: Similarly, the city of Stockholm’s recent gains have not been the result of migration from the suburbs. Between 2001 and 2007, the city lost a net 8,000 domestic migrants. This loss was more than made up by the international net migration of 29,000. At the same time, the suburbs and exurbs gained 15,000 domestic migrants.

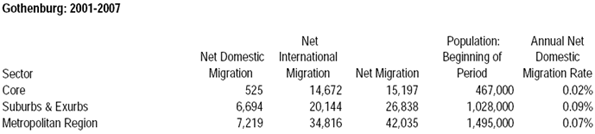

Sweden’s second largest metropolitan area, Gothenburg, was one of only two of the 19 cases in which there was net domestic migration to the core (which had been enlarged in the 1990s to include many suburban areas). The city gained 500 domestic migrants and 15,000 international migrants. However, the suburbs gained approximately 13 times as many domestic migrants than the city, again indicating no trend of movement from the suburbs to the city.

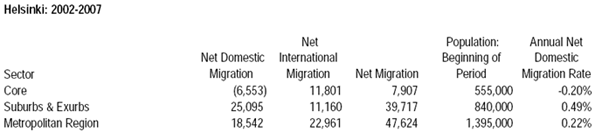

Helsinki: Finland’s capital mirrors the general trend. The city of Helsinki lost 6,500 domestic migrants between 2002 and 2007, which was more than compensated for by an 11,800 net international migration gain. As in nearly all of the other cases, the suburbs and exurbs gained domestic migration, illustrating that there is not a movement from the suburbs to the city in Helsinki.

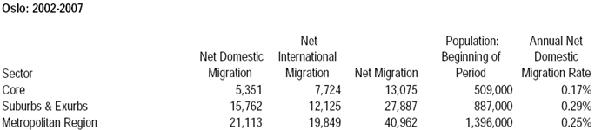

Oslo: Norway’s capital was, with Gothenburg, the only core experiencing net domestic migration. Oslo County gained 5,400 domestic migrants. However, the suburbs and exurbs gained domestic migrants at a greater rate, adding 16,000. Thus, despite the core domestic migration gains, there is no evidence of a “return” from the suburbs and exurbs to the city in Oslo.

Conclusion: The available data from national census authorities provides no evidence to suggest any sort of general movement of the population from suburban and exurban areas to the central cities of Western Europe. This mirrors the situation in the United States, where interests that hold the suburbs in contempt continue to declare their death, while the latest data continues to show the opposite – strong domestic migration losses in core areas and gains in the suburbs.

There is one other key factor in the European case: the enlargement of the European Union in 2004, which increased the national membership from 15 to 25 (and subsequently to 27) and allowed for the mass migration of people from the east to the wealthier west. Whether the international financial crisis may reverse this trend, with many Eastern European residents moving back to their native countries, remains an open question.

Note on European metropolitan areas: There is no European standard for determining metropolitan areas (which are labor markets). The European Audit’s “Larger Urban Zones” (LUZ) are the closest approximation, but are not consistently defined throughout the European Union. For example, the Naples LUZ includes only the core and inner suburbs, an area far smaller than the functional metropolitan area. Many other larger urban zones include suburban and exurban areas, consistent with the concept of a metropolitan area.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

I like this post,And I guess

I like this post,And I guess that they having fun to read this post,they shall take a good site to make a information,thanks for sharing it to me.

hsk 5 grammar

This is a great inspiring

This is a great inspiring article.I am pretty much pleased with your good work.You put really very helpful information...

NITROvit Review

A lot of people are

A lot of people are migrating or moving to urban areas such as big cities ant metropolitan areas to look for better opportunities and seek jobs. Due to this, urban areas are now crowded and pollution increased as people flocking to these areas. From a limited span of time there are thousands of people reportedly now living to these places.

business storage

A business storage is likely

A business storage is likely trending today. It would be great if we take advantage of it while it's on demand. Movers may pay a huge amount just to move their stuff to their new place.

_Visit: tu van dau tu nuoc

_Visit: tu van dau tu nuoc ngoai, cong bo thuc pham, thiet ke website ban hang, thanh lap cong ty, dang ky nhan hieu, cong bo luu hanh my pham...

These are some interesting

These are some interesting trends, if I owned a moving service company I would pay attention to them, being able to predict what comes next can make the difference between success or failure. They'd better start building self storage units in key points, they'll be on high demand.