NewGeography.com blogs

The Wall Street Journal reports that China will slow down its world's fastest high speed rail trains. According to the Journal, Sheng Guangzu, head of China's Ministry of Railways, told the People's Daily that the decision will make tickets more affordable and improve energy efficiency on the country's high-speed railways. The maximum speed will be 300 kilometers per hour (186 miles per hour), which is also the top speed for most high speed rail trains in Japan, France, Korea and Taiwan. The United Press reported that the 300 kph service would be limited to the four north-south (Beijing to Harbin, Beijing to Shanghai, Beijing to Hong Kong and Shanghai to Shenzhen) and east-west lines (Qingdao to Taiyuan, Lanzhou to Xuzhou, Shanghai to Chengdu and Shanghai to Kunming). Both sources were unclear as to whether the new speed limit would apply to the proposed 380 kph Beijing to Shanghai line, however that line is one of the four north-south trunk routes, all of which will operate at the slower speed according to the Ministry of Railways.

Currently, the world's fastest high speed rail trains operate on the Guangzhou (South Station) to Wuhan route, which reaches 350 kilometers per hour on its fastest service (which stops in Changsha, the non-stop service having been cancelled), completing the run in 3:16. This lower speed could increase travel time on the route to between 3:30 and 3:45.

The Journal cited a high-speed rail official (not Chinese) who indicated that there are safety concerns with trains running at above 320 kph. In contrast, the proposed California high speed rail line would operate at top speeds of 355 kph.

Photo: Nanjing high speed rail train, Shanghai Station (by author)

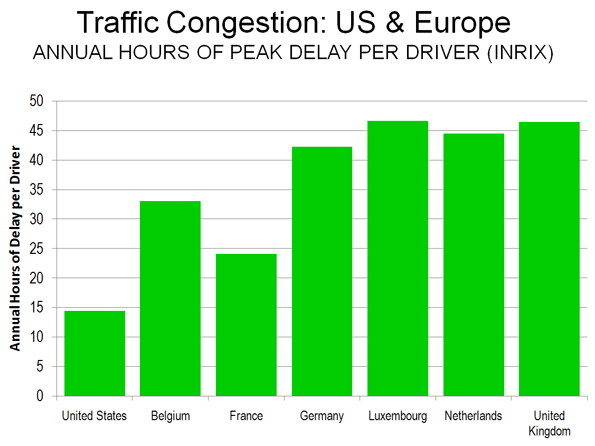

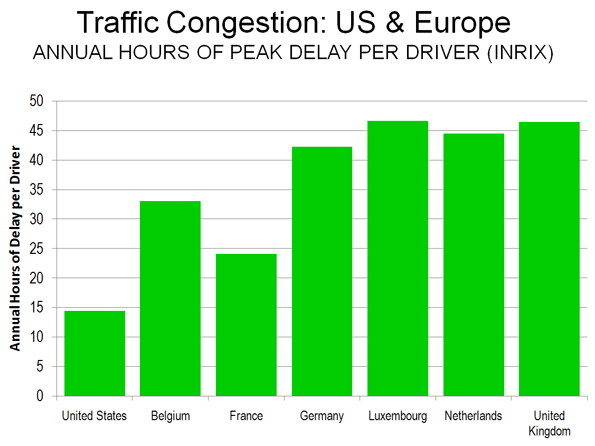

A new international report indicates that traffic congestion in the United States is far better than in Europe. The report was released by INRIX, an international provider of traffic information in 208 metropolitan areas in the United States and six European nations.

The report shows that the added annual peak hour congestion delay in the United States is roughly one-third that of Europe. The rate of France was somewhat less than twice the rate of the US and rates in Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Germany and the Netherlands were three times as high.

In the United States, peak period traffic congestion adds 14.4 hours annually per driver. This compares to an average delay per year of 39.5 hours for the European nations. Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Germany had the greatest lost time, at from 42 to 47 hours. Again, France scored the best in Europe, at 24.1 hours of lost time in traffic per year (Figure).

Among individual metropolitan areas. Los Angeles had the greatest peak hour delay, at 74.9 hours annually. Utrecht (Netherlands), Manchester (United Kingdom), Paris, Arhem (Netherlands) and Trier (Germany) second through sixth in the intensity of traffic congestion, all with 65 or more hours of delay per driver per year.

These findings are consistent with international data indicating that traffic congestion tends to be more intense where there are higher urban population densities.

The Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s cutbacks on its bus line, eliminating about 12% bus service, illuminate the problems of mass transit in LA, specifically the relative inefficiency of trains in the city. This 12% is a further reduction after the 4% cutbacks six months ago, sparking anger from the Bus Riders Union. Metro Chief Executive Art Leahy says that his decision to decrease spending is a result of the low ridership, yet city trains, which are also underperforming, remain relatively untouched.

Leahy argues that buses are easier to eliminate, re-route, and reschedule than rail lines are. However, he also says that the cutting back on lesser-used bus lines will free up the resources to enhance the ones in higher demand. Many bus riders feel that they are getting a raw deal seeing as bus lines, which transport 80% of the MTA’s passengers, only get 35% of the operating budget to begin with. This being true, how much is the other 65% really helping the rail lines then?

The Bus Riders Union thinks that the MTA’s preference for trains over buses is an unfair reflection of class interests. Because rich people do not take the bus, there is no incentive to keep it running. As is becoming increasingly clear, especially with the current high-speed rail discussions, rich people don’t want to ride the train anymore either. This local debate, therefore, is not an argument of whether to cutback on buses or trains; it is an argument about how to deal with the general decline in mass transit.

I’ve spent a good chunk of the last few months working on a study of Calgary’s light rail transit (C-Train) system, which was released today by the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. I’ve had a long standing interest in LRT systems, and spent the summer of 2009 working for the Cascade Policy Institute in Oregon, where we compiled massive amounts of data on their world renowned LRT system as part of an ongoing project. The data (including actual field research, which proponents of the system haven’t done–they rely on survey data), indicates that ridership is lower, and costs are far higher than proponents believe.

That firsthand experience (which included riding the train every day), coupled with the empirical literature from light rail systems across North America, shattered my previous conviction that light rail transit can be an economical method of transit. For the record, I do believe that subways can be profitable in dense urban cores (even the badly managed TTC nearly breaks even), and buses already are profitable in many cases (especially inter-urban bus services, such as Greyhound and Megabus). Many proponents of LRT believe that it is a happy medium between subways and buses. If that were the case, it would be profitable. However, LRT combines the disadvantages of the two: it is slow, inflexible, and expensive. Numerous studies, in particular an authoritative study by the non-partisan United States Government Accountability Office, have demonstrated that on average, buses are a cheaper, faster, and more flexible than LRT for providing mass transit.

While I use many different metrics to demonstrate that the costs and benefits of LRT are wildly exaggerated, my favorite is that Calgary spends both the most on transit and the most on roads per-capita. Given that Calgary’s entire land use and transportation framework for the past several decades has been built around the C-Train, it is hard to call it anything but a failure. The City has cracked down on parking so aggressively to encourage people to ride the train that there are only 0.07 parking spaces per employee in the central business district. Because of this, Calgary is tied with New York for the highest parking prices on the continent. But many of those people who would otherwise have parked downtown instead park in the free parking spots provided at C-Train stations. Not only is free parking horribly inefficient, but this also emphasizes one of the major contradictions of the C-Train: it isn’t getting people out of their cars, and it isn’t helping to curb urban sprawl–two of its primary goals.

Unsurprisingly, those last two findings proved controversial, though not as controversial as my assertion that the C-Train fails to help the urban poor. A columnist for the Calgary Herald wrote an angry response to my Herald article that accompanied the story (though doesn’t seem to have read the study). She attempts to refute my arguments about urban sprawl, and the impact of the C-Train on the poor, while dismissing the study as “a cost-benefit analysis guaranteed to resonate with other right wingers who share the mantra of lower taxes above all else, including over the reality of everyday experience.” I’m not clear on when cost-benefit analysis became a right wing concept, but I’ll let that one go. I will, however, address her two criticisms in short order.

The idea that urban transit could worsen sprawl seems odd. The reason why it does so in Calgary is because the C-Train network is built on a hub and spoke model. What this means is that transit is concentrated on going from the outskirts, into the city center. Since LRT is so expensive, and since people need to be ‘collected’ by buses to get to LRT stations, the city has less resources to provide transit circling the core, or travelling east-west. And if you can’t provide good transit for people who aren’t living along LRT lines, and don’t work along one of the lines, people are just going to keep moving further out (hence the highest road costs in the nation). Here’s what Calgary Transit’s current planning manager has to say about the C-Train’s impact on sprawl:

“In one respect, it should allow Calgary to be a more compact city, but what it’s done is it’s actually allowed Calgary to continue to develop outward because it was so easy to get to the LRT and then get other places,” says Neil McKendrick, Calgary Transit’s current planning manager.”

While that comment is true for those who can afford to live by LRT stations (or to drive to them), it doesn’t apply to the city’s poorest. As it happens, LRT lines raise the cost of adjacent housing (though for proximate high end housing it lowers the value–hardly a concern for the poor)–by $1045 for every 100 feet closer to a rail station. This isn’t a terribly complicated concept. If you spend a massive amount of money on a form of transit that is considered to luxurious, the price of housing goes up. This is exacerbated by the fact that diverting transit resources to those areas makes transit there comparatively better, making it that much more desirable comparatively for people who intend to use transit at all–even as just an occasional amenity, say for going downtown on weekends. LRT is great for people who can afford to live by the stations, but not so much for anyone else.

Unfortunately, for many, light rail transit has become a sacred cow. But if Calgary is ever going to have adequate rapid transit, the City will need to explore more cost effective options. Buses may not be trendy, but expanding BRT in Calgary would dramatically improve people’s mobility at a reasonable cost. Fortunately, the current Mayor has acknowledged that BRT will have to be part of the solution for making Calgary a transit friendly city. He also made the wise decision of de-prioritizing the southeast LRT extension (expected to cost $1.2-$1.8 billion). If the Mayor follows up on his promise to make BRT an integral part of Calgary Transit in the short term, the City will not only have far better transit, but it will have a chance to watch the LRT and BRT operating side by side so that the people can decide for themselves whether the billion plus required to build the Southeast LRT is worthwhile. My bet is on BRT.

This piece originally appeared at stevelafleur.com

Zhengzhou, Henan, China (March 28, 2011): In December, London’s Daily Mail reported that the Zhengzhou New Area was China’s largest “Ghost City.” A visit to the Zhengzhou New Area indicates exactly the opposite. Chinese “Ghost Cities” are large areas of new development that are virtually unoccupied. The most famous example is Ordos, a new and reportedly empty city, built to replace an older city in Inner Mongolia.

Zhenghou is an urban area of approximately 2.5 million population and is the capital of Henan province. The Zhengzhou New Area is located in the northeastern quadrant of Zhengzhou. It is circular in design, with two parallel roads, high-rise condominium buildings on the inner ring and commercial buildings on the outer ring. The interior of the circle includes the Henan Arts Center and a skyscraper that is under construction. A new high speed rail station is under construction to serve the new Guangzhou to Beijing line. The station is to be one of the largest in Asia.

Our visit revealed anything but a Ghost City. Granted, no-one would mistake the traffic for Beijing Third Ring Road volumes, but virtually all of the parking spaces were taken and there was traffic on the streets (Figure 1). That ultimate indicator of Chinese urbanization, the availability of frequent taxicab service was well in evidence. Two of the city’s bus rapid transit lines serve the interior circle road, again indicating a substantial threshold of non-ghost urbanization.

There were people on the sidewalks, though not the numbers typical of an older, more dense section of a Chinese urban area (Figure 2). It was clear from the laundry hanging in glass enclosed patios that many of the condominiums were occupied, though it is to be expected that many would not be, given the Chinese propensity to invest in multiple residential properties (a tendency the central government seeks to curb). Many of the commercial skyscrapers were occupied, and some were still under construction. There are also shopping centers, small stores and fast food restaurants.

Zhengzhou New Area is intended by the developers to become the new central business district for Zhengzhou. There is much more planned than this first phase. Eventually, the Zhengzhou New Area is intended to cover 105 square kilometers (41 square miles), generally further to the northeast. City maps already show the planned street pattern, not unlike 19th century maps of some US cities.

In short, the Zhengzhou New Area is alive and not a Ghost City. It may well be that it took longer than expected for the place to come alive. But it is clear that the life of the Zhengzhou New Area began more than four months ago.

|