NewGeography.com blogs

Each year, chiefexecutive.net ranks states based upon their business competitiveness. The latest rankings have just been published in 2013: Best and Worst States for Business.

Texas on Top: For the 9th Year in a Row

For the ninth year in a row, chiefexecutive.net ranks Texas as the most business friendly state. Noting the Texas cost of living advantage, chiefexecutive.net points out that “Young programmers and engineers can actually afford to live well in Austin, where the housing cost index is 300 percent lower than in San Francisco.”

It is not surprising that Austin has emerged as the fastest growing metropolitan area in the United States adding 3.1 percent to its population annually since 2010. This is an astounding rate of growth --- twice that of the San Jose IT behemoth, which at current rate of growth will fall behind Austin in population by 2015. Austin’s growth rate is faster than some of the fastest growing developing world cities, such as Mumbai, Dhaka and Manila.

However there is much more to Texas Austin. Dallas-Fort Worth is the fastest growing metropolitan area with more than 5 million people in the high income world, though at an average annual growth rate since 2010 of 1.9234 percent retains only a narrow lead over similar sized Houston (1.9227 percent). Smaller San Antonio is growing marginally more quickly both Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston (though less than 2 percent).

Texas was joined in the top five by the South’s Florida, North Carolina and Tennessee, as well as Indiana, from the Midwest. Three of the top five (Texas, Florida and Tennessee) do not have a state income tax and chiefexecutive.net notes that other states are looking at tax reform that would improve the business climate.

California: Bringing Up the Rear for the 9th Year in a Row

Just as predictably as Texas ranking first, California has secured the bottom position for the ninth year in a row. A California CEO told chiefexecutive.net“On any particular element, if New Jersey is an ‘8’ on the pain-in-the-ass scale, California is a ‘9 … It’s an ungovernable state, and there’s no movement that will change that, though there are people who want to…”

Nearly as predictably, California is joined in the bottom five by older northeastern states New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts as well as Illinois, from which, like California, hundreds of thousands, even millions of people have fled since 2000.

The complete state rankings can be viewed at http://chiefexecutive.net/best-worst-states-for-business-2013.

There have been two universal reactions to my announcement that I was going to move from Portland to the Midwest: surprise and disbelief. But I also found a number of people who, if given a few moments to find clear and honest footing in the conversation, could see through the self-absorbed mental fog that covers the city in equal measure to the grey rain clouds and tells its inhabitants every day that Portland is the most amazing possible place in this country to live. The amount of media devoted to reinforcing this idea is overwhelming in the sense that I believe it has overwhelmed people’s ability to have their own thoughts and identity in Portland. Instead they have a Portland identity…because they live in Portland and that is what defines them.

On the surface, Portland has many progressive aspects. Sustainability and the “greening of the city” stand front and foremost as two easily recognized. Curbside recycling and composting, increasing investment in bicycle transportation, native gardening, and urban farming. There is an intense concentration of a wide range of alternative health practitioners. Artisan craftspeople abound, creating specialty foods and other handcrafted products. “Shop local” is the resounding cry to support small businesses, and farmers markets adorn every neighborhood in the summertime.

Idyllic as this sounds, there is a less appealing aspect to this picture. As Portland concentrates is cultural practices into a few baskets, the proliferation of other ideas diminishes. Ten years ago I would have characterized Portland as a place that had progressive perspectives. Now I would characterize Portland as a place with few ideas, all perpetually reinforced and more deeply ingrained every day. People regurgitate a handful of versions of the same thoughts in ever narrowing expressions. Everywhere you look it is repetition of the same ideas, whether it be on politics, design, or social culture. People strive to look the same, to dress the same, and to have the same lifestyle. It is so pervasive, that women within a 30 to 40 year age range may display similar choices in hair, dress, and accessories. What began as a city with progressive and forward looking ideas to develop a new urban course has become a closed container of cultural conformity. There is a new cookie cutter in Portland, and it is young, alterna-hip, and white.

I grew up in a place like this…it is called Orange County.

Sweeping shocked gasps aside, this comparison is worth a long pause to consider. Stripping away the key difference between Multnomah and Orange County of political affiliation, with Orange County being a historic Republican stronghold and Portland staunchly Democrat, these two counties have some key cultural similarities all hinging on a pivotal word used above: conformity. Conformity of dress, thought, and mannerisms, shared ideas and ideals, and a strong attitudinal belief that there is a “right” or “correct” way to be and to appear to others. There is also limited interest or investment in the arts, creative, innovative, or intellectual development. Just because the surface ideals these two places seem extremely different from each other, does not mean that they don’t breed the same obedience to a self-referencing norm within themselves. And by perpetuating their particular cultures and tailoring their environments to fit with a narrow range of ideals, the inhabitants of these areas increasingly live on the margins of reality and instead inhabit a fabricated cocoon of their own self-rewarding design.

What disturbed me most about Portland in the months leading up to my decision to leave was the increasingly strong social culture of invisibility. I am referring to the tendency of people in Portland to not acknowledge the physical presence of other people around them in close proximity. This can easily be seen by the increasing tendency of people to brush past you without making eye contact or saying “excuse me” and instead being intensely focused on some spot just beyond your left shoulder. But it manifests in countless other ways: letting dogs off leash (and not picking up after them), ignoring red lights and stop signs, allowing children license to act out without discipline in the presence of other adults.

In this city where conformity to a particular identity is so strong, people no longer see each other as people. People come in and out of your field of vision as an object to be ranked according to usefulness to you, and invariably avoided, ignored and dismissed the majority of the time. It is unpleasant, unsettling and dehumanizing. The countless tiny social interactions we have with other people throughout the day are the glue that hold us together as a community and keep us from being automatons randomly bumping into one another like the balls in a pinball machine. This critical stickiness in Portland is dissolving rapidly. As people lose the ability to engage and connect with one another, there appears to be an increasingly growing level of resentment, frustration and anger brewing under the surface of social interactions. Not just interactions where overt conflict is involved, but all of them. Because it feels like they all contain some level of conflict just by the occurrence of people being together in a place, time and circumstance.

There is little likelihood that I would ever have been physically assaulted in Portland. But I think there is a pretty strong likelihood that if I were physically assaulted that no one around me would react or get involved or help. Because chances are, I wouldn’t even be seen.

When confronted with difficult situations or challenging environments, often it is heard “it’s the people that keep me here…keep me working, living, etc. in this place despite its shortcomings”. In Portland, the situation is reversed….the environment is being made increasingly pleasant and comfortable, but it is the people that make it so difficult to live there.

Read Jennifer Wyatt’s blog about her cross country move at isaymissourah.wordpress.com.

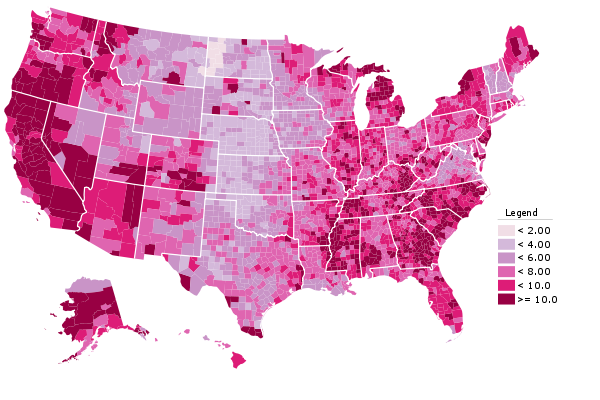

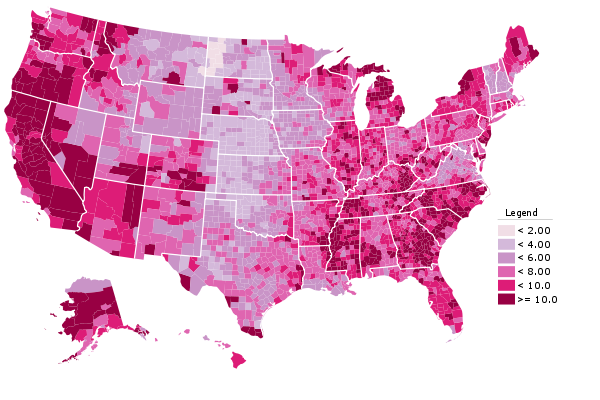

I recently looked at the changes in jobs in metro areas for 2012. Here’s a follow-on look at unemployment. First a look at the national unemployment rate picture, which has improved remarkably.

2012 Unemployment Rate by County

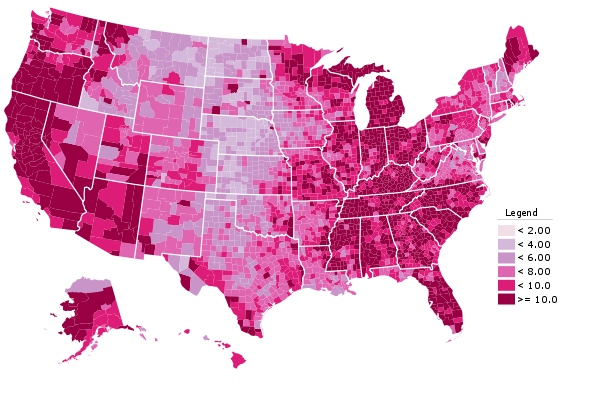

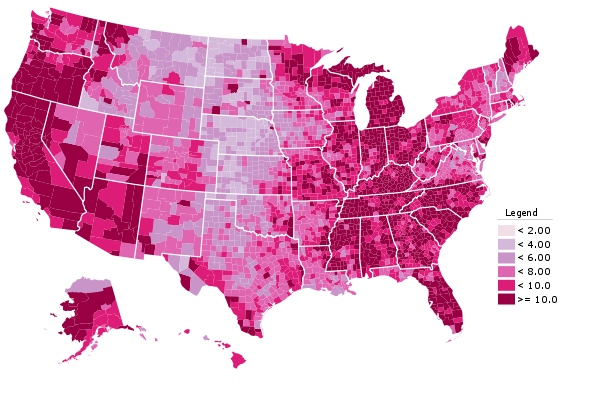

To put this in perspective, here’s the corresponding map for 2009:

2009 Unemployment Rate by County

It’s interesting to see where there has been improvement versus where there hasn’t, though I stop thresholding at 10% so that if people we well above it but dropped to just merely above it, my maps wouldn’t show that improvement.

Here’s a look at the large metro areas, ranked by total decline in unemployment rate.

| Rank by Total Improvement |

Metro Area |

2011 |

2012 |

Total Change |

| 1 |

Las Vegas-Paradise, NV |

13.5 |

11.2 |

-2.3 |

| 2 |

Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL |

10.2 |

8.4 |

-1.8 |

| 3 |

Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL |

10.6 |

8.8 |

-1.8 |

| 4 |

Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL |

10.2 |

8.5 |

-1.7 |

| 5 |

Jacksonville, FL |

9.9 |

8.3 |

-1.6 |

| 6 |

Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA |

11.9 |

10.4 |

-1.5 |

| 7 |

Birmingham-Hoover, AL |

7.9 |

6.4 |

-1.5 |

| 8 |

Cincinnati-Middletown, OH-KY-IN |

8.6 |

7.1 |

-1.5 |

| 9 |

Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA |

13.6 |

12.1 |

-1.5 |

| 10 |

Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN |

8.1 |

6.6 |

-1.5 |

| 11 |

Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN |

9.7 |

8.3 |

-1.4 |

| 12 |

San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA |

10.0 |

8.6 |

-1.4 |

| 13 |

Columbus, OH |

7.5 |

6.1 |

-1.4 |

| 14 |

Kansas City, MO-KS |

8.0 |

6.6 |

-1.4 |

| 15 |

Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX |

8.1 |

6.8 |

-1.3 |

| 16 |

Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill, NC-SC |

10.8 |

9.5 |

-1.3 |

| 17 |

Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA |

8.7 |

7.4 |

-1.3 |

| 18 |

San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA |

9.4 |

8.1 |

-1.3 |

| 19 |

Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA |

11.4 |

10.1 |

-1.3 |

| 20 |

Salt Lake City, UT |

6.7 |

5.5 |

-1.2 |

| 21 |

Phoenix-Mesa-Glendale, AZ |

8.5 |

7.3 |

-1.2 |

| 22 |

St. Louis, MO-IL |

8.8 |

7.6 |

-1.2 |

| 23 |

Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX |

7.8 |

6.7 |

-1.1 |

| 24 |

San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA |

10.0 |

8.9 |

-1.1 |

| 25 |

Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI |

11.6 |

10.5 |

-1.1 |

| 26 |

Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA |

9.3 |

8.2 |

-1.1 |

| 27 |

Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA |

9.8 |

8.8 |

-1.0 |

| 28 |

Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, TX |

6.8 |

5.8 |

-1.0 |

| 29 |

San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX |

7.5 |

6.5 |

-1.0 |

| 30 |

Memphis, TN-MS-AR |

10.0 |

9.0 |

-1.0 |

| 31 |

Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI |

9.8 |

8.9 |

-0.9 |

| 32 |

Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI |

6.3 |

5.5 |

-0.8 |

| 33 |

Raleigh-Cary, NC |

8.5 |

7.7 |

-0.8 |

| 34 |

Providence-Fall River-Warwick, RI-MA – Metro |

11.1 |

10.3 |

-0.8 |

| 35 |

Richmond, VA |

7.1 |

6.4 |

-0.7 |

| 36 |

New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA |

7.2 |

6.5 |

-0.7 |

| 37 |

Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH |

7.8 |

7.1 |

-0.7 |

| 38 |

Oklahoma City, OK |

5.5 |

4.8 |

-0.7 |

| 39 |

Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO |

8.6 |

7.9 |

-0.7 |

| 40 |

Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT – Metro |

9.0 |

8.4 |

-0.6 |

| 41 |

Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI |

8.0 |

7.4 |

-0.6 |

| 42 |

Indianapolis-Carmel, IN |

8.4 |

7.8 |

-0.6 |

| 43 |

Baltimore-Towson, MD |

7.7 |

7.2 |

-0.5 |

| 44 |

Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC |

7.1 |

6.6 |

-0.5 |

| 45 |

Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH – Metro |

6.6 |

6.1 |

-0.5 |

| 46 |

Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV |

6.0 |

5.6 |

-0.4 |

| 47 |

Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

8.6 |

8.6 |

0.0 |

| 48 |

Pittsburgh, PA |

7.2 |

7.2 |

0.0 |

| 49 |

New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA |

8.6 |

8.8 |

0.2 |

| 50 |

Rochester, NY |

7.8 |

8.1 |

0.3 |

| 51 |

Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY |

8.1 |

8.5 |

0.4 |

Over the last few decades, humans achieved one of the most remarkable victories for social justice in the history of the species. The percentage of people who live in extreme poverty — under $1.25 per day — was halved between 1990 and 2010. Average life expectancy globally rose from 56 to 68 years since 1970. And hundreds of millions of desperately poor people went from burning dung and wood for fuel (whose smoke takes two million souls a year) to using electricity, allowing them to enjoy refrigerators, washing machines, and smoke-free stoves.

Of course, all of this new development puts big pressures on the environment. While the transition from wood to coal is overwhelmingly positive for forests, coal-burning is now a major contributor to global warming. The challenge for the 21st Century is thus to triple global energy demand, so that the world's poorest can enjoy modern living standards, while reducing our carbon emissions from energy production to zero.

For the last 20 years, most everyone who cared about global warming hoped for a binding international treaty abroad, and some combination of carbon pricing, pollution regulations, and renewable energy mandates at home. That approach is now in ruins. In 2010, UN negotiations failed to create a successor to the failed Kyoto treaty. A few months later cap and trade died in the Senate. And two weeks ago, the slow motion collapse of the European Emissions Trading Scheme reached its nadir, with carbon prices, already at historic lows, collapsing after EU leaders refused to tighten the cap on emissions.

What rushed into the vacuum was "climate justice," a movement headed by more left-leaning groups like 350.org, the Sierra Club, and Greenpeace. These groups invoke the vulnerability of the poor to climate change but elide the reality that more energy makes them more resilient. "Huge swaths of the world have been developing over the last three decades at an unprecedented pace and scale," writes political scientist Christopher Foreman in "On Justice Movements," a new article (below) for The Breakthrough Journal. "Contemporary demands for climate justice have been, at best, indifferent to these rather remarkable developments and, at worst, openly hostile."

For the climate justice movement, global warming is not to be dealt with by switching to cleaner forms of energy but rather by returning to a pastoral, renewable-powered, and low-energy society. "Real climate solutions," writes Klein, "are ones that steer these interventions to systematically disperse and devolve power and control to the community level, whether through community-controlled renewable energy, local organic agriculture or transit systems genuinely accountable to their users…"

Climate change can only be solved by "fixing everything," says McKibben, from how we eat, travel, produce, reproduce, consume, and live."It's not an engineering problem," McKibben argued recently in Rolling Stone, "it's a greed problem." Fixing it will require a "new civilizational paradigm," says Klein, "grounded not in dominance over nature but in respect for natural cycles of renewal."

Climate skeptics are right, Klein cheerily concludes: the Left is using climate change to advance policies they have long wanted. "In short," says Klein, "climate change supercharges the pre-existing case for virtually every progressive demand on the books, binding them into a coherent agenda based on a clear scientific imperative."

As such, global warming is our most wicked problem. The end of our world is heralded by ideologues with specific solutions already in mind: degrowth, rural living, low-energy consumption, and renewable energies that will supposedly harmonize us with Nature. The response from the Right was all-too predictable. If climate change "supercharges the pre-existing case for virtually every progressive demand," conservatives long ago decided, then climate change is either not happening, or is not much to worry about.

Wicked problems can only be solved if the ideological discourses that give rise to them are disrupted, and that's what political scientist Foreman does brilliantly in "On Justice Movements." If climate justice activists truly cared about poverty and climate change, Foreman notes, they would advocate things like better cook stoves and helping poor nations accelerate the transition from dirtier to cleaner fuels. Instead they make demands that range from the preposterous (e.g., de-growth) to the picayune (e.g., organic farming).

Once upon a time, social justice was synonymous with equal access to modern amenities — with electric lighting so poor children could read at night, with refrigerators so milk could be kept on hand, and with washing machines to save the hands and backs of women. Malthus was rightly denounced by generations of socialists as a cruel aristocrat who cloaked his elitism in pseudo-science, in the claim that Nature couldn't possibly feed any more hungry months.

Now, at the very moment modern energy arrives for global poor — something a prior generation of socialists would have celebrated and, indeed, demanded — today's leading left-wing leaders advocate a return to energy penury. The loudest advocates of cheap energy for the poor are on the libertarian Right, while The Nation dresses up neo-Malthusianism as revolutionary socialism.

Left-wing politics was once about destabilizing power relations between the West and the Rest. Now, under the sign of climate justice, it's about sustaining them.

This piece originally appeared at The Breakthrough.

by Anonymous 04/21/2013

President Obama's FY 2014 budget request includes $77 billion for the Department of Transportation and an additional $50 billion "for immediate transportation investments." His next transportation bill to follow the current MAP-21, calls for a 25 percent increase in funding over current levels and assumes a transfer of $214 billion to the trust fund over six years "to maintain trust fund solvency and pay for increased outlays." To offset this spending, the Administration proposes using the "savings" or "peace dividend" from winding down the war in Afganistan.

House T&I Committee Chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA) was not impressed. "The President's budget," he said, "repeats his call to increase spending without identifying a viable means to pay for it. .... You can't just keep on spending money that you don't have." "A proposal we have seen three times before," observed Rep. Tom Latham (R-IA), House Transportation Appropriation Subcommittee chairman referring to the $50 billion request. With massive stimulus spending politically out of fashion, the Administration is repackaging it as "transportation investment." Bill Graves, president of the American Trucking Association, spoke for many stakeholders when he remarked, "For five years, we've waited for President Obama to clearly state how we should pay for these critical needs and, I'm sad to say, we continue to get lip service about the importance of roads and bridges with no real road map to real funding solutions." As for the "peace dividend," the idea has been dismissed as "budgetary gimmickry" by congressional Democrats and Republicans alike.

In sum, a large segment of congressional and public opinion has pronounced the White House proposals variously as "vague", "repetitive," "unrealistic," "implausible" and "politically unachievable." Even the President's most loyal supporters in the transportation community, the liberal advocacy groups, seemed disappointed and circumspect in their comments.

This said, no one disputes President Obama's and the infrastructure advocates’ claim that some of America’s transportation facilities are reaching the limit of their useful life and need reconstruction. Nor does any one disagree about the need to expand infrastructure to meet the needs of a growing population. But fiscal conservatives among infrastructure advocates (and we count ourselves among them) contend that this does not rise to the level of a national crisis requiring a massive $50 billion federal crash program as proposed in the President's budget message, or the expenditure of more than $100 billion per year as recommended by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) in its latest "Report Card."

Instead, as we have argued in recent columns, the challenge can be met if each state did its part to progressively bring up its transportation facilities (including its Interstate highway segments) to a "state of good repair," using its own tax revenues and its formula allocation of the Highway Trust fund dollars (which are expected to total $38-41 billion per year over the next decade.) As numerous news dispatches attest, that's precisely what is happening (see below). A large number of states are not waiting for the federal government to come to the rescue. They are using their own resources and raising additional revenue to pay for reconstruction and modernization of their aging facilities and to maintain their transportation systems in good working condition. "Governors and state legislatures realize that the level of federal assistance beyond 2014 is highly uncertain and they are acting on a credible assumption that federal funding will remain at current levels or may even be cut back," an association executive who is familiar with the thinking of senior-level state officials, told us.

What about large-scale reconstruction and system-expansion projects that require billions of dollars---transportation investments that are beyond the states' fiscal capacity to fund on a pay-as-you-go basis out of annual cash flow? Those investments, provided they are credit-worthy (i.e. are revenue producing or backed by dedicated tax revenue), will be mostly financed through long-term credit instruments and public-private partnerships. The future of capital-intensive infrastructure projects is intimately tied to the financial involvement of the private sector and to a wider use of tolling, "availability payments," and innovative credit instruments such as TIFIA and private activity bonds (PABs), a veteran facilitator of public-private partnerships told us. We list below some of the transportation megaprojects that are being financed (or are planned to be financed) largely with public and private credit rather than with federal dollars out of congressional appropriations.

###

Lending credibility to the above funding scenario and hastening its adoption are the new realities underlying the federal role in transportation today. Those realities include: (1) a federal program that no longer has a clearly defined mission or purpose and many of whose functions are properly a state and local responsibility; (2) a Highway Trust Fund that has lost its capacity to support large-scale transportation investments and that has come to depend for its solvency on periodic injections of general funds; (3) a bipartisan absence of political will to raise the federal gas tax and (4) continued inability to identify another credible revenue source to supplement or replace the gas tax.

In sum, having the states assume financial responsibility for fixing their aging transportation facilities and for preserving them in a state of good repair, while employing public and private financing for major capital-intensive infrastructure investments, offers the best solution to the current federal funding dilemma.

NOTE: States that recently have undertaken to raise additional funds for transportation include: Virginia and Maryland (broad transportation funding overhaul that includes a dedicated sales tax applied to the wholesale price of gasoline. A sales tax, it has been argued, is no less a "user fee" than the gas tax since every consumer who pays a sales tax also is served by or "uses" the highway system for goods delivery ); Arkansas (one-half cent sales tax increase to back a $1.3 billion bond issue to fund highway construction over the next ten years); Illinois (six-year $12.6 billion statewide construction program to improve roads and bridges); Massachusetts ($13.7 billion bond-financed transportation plan); Maine ($100 million transportation bond proposal) Michigan ( $1.5 billion road plan funded with vehicle registration fees and a tax on fuel at the wholesale level); Missouri (proposal for a dedicated one-cent sales tax for transportation; the tax is expected to raise $7.9 billion over ten years); New Hampshire (12-cent hike in the gas tax over three years approved by the House; Senate approval uncertain); Ohio (turnpike toll-backed $1.5 billion bond issue for highway and bridge improvements); Pennsylvania ($2.5 billion Senate transportation funding plan; House approval uncertain); Texas (statewide tolling); Wisconsin ($824-million boost to the state transportation fund); Wyoming (10-cent fuel tax increase, the first in 15 years); and California, Oregon and Washington (exploring new mechanisms for project finance through the cooperative West Coast Infrastructure Exchange). In addition, several states which derive significant revenue from their tollroads have raised toll rates. See also, "State Transportation Funding Proposals, AASHTO Center for Excellence in Project Finance, April 2013

Recent major transportation infrastructure projects largely financed,or to be financed, with long-term credit instruments rather than federal dollars include: the I-495 Beltway HOT lanes project in Northern Virginia; New York's Tappan Zee Bridge replacement; the San Francisco Bay Bridge Eastern Span replacement; the I-5 Columbia River Crossing; the Highway 520 floating bridge and the Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle, the Midtown tunnel linking Norfolk and Portsmouth, VA; East End Crossing over the Ohio River near Louisville; and the PortMiami Tunnel. Please note that, except for the California High-Speed Rail venture, there are no transportation megaprojects currently being planned whose construction would depend primarily on federal appropriations.

|