In May, disgruntled workers of Honda factories in Zhongshan, southern China, went on strike at the Honda Lock auto parts factory and started posting accounts of the walkout online, spreading word among themselves and to workers elsewhere in China.

In June, Bloomberg reported that China, “once an abundant provider of low-cost workers, is heading for the so-called Lewis turning point, when surplus labor evaporates, pushing up wages, consumption and inflation.” China had depleted its surplus labor; the period of cheap labor was over.

In the subsequent debate, some observers concurred with the observation that a turning point had arrived in China. Others noted that the conclusion is too simplistic because it does not fit into the big picture of China’s demography.

With the gloomy economic prospects in the advanced economies and relatively strong recovery in the large emerging economies, the debate is about to resurface.

Eclipse of “Unlimited Supplies of Labor”

In 1954 Arthur Lewis published one of the most influential development economics articles, “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor,” which contributed to his Nobel Prize a quarter of a century later. In this paper, Lewis sought to provide a broad portrayal of the development process, based on the current state of the developing countries, the historical experience of developed countries, and some central ideas of the classical economists.

In the Lewis story a “capitalist” sector develops by taking labor from a non-capitalist backward “subsistence” sector. At an early stage of development, there would be “unlimited” supplies of labor from the subsistence economy, which means that the capitalist sector can expand without the need to raise wages. The implication is that industrial wages in developing countries begin to rise quickly at the point when the supply of surplus labor from the countryside tapers off.

Lewis likely would have recognized the validity of his tipping point in the more prosperous first-tier cities of China where there clearly are increasing labor shortages and which thus reflect the world of classical economics. However, had he taken a tour in China’s smaller cities, or ventured into the countryside, he would have recognized there still remains “unlimited supplies of labor” – the world portrayed by the classical political economists, including David Ricardo, Adam Smith, and Karl Marx.

So has China reached the Lewisian tipping point? The answer is yes and no: in some regions yes, but in all of China, emphatically n no.

Urbanization and Growth through Tiered Cities

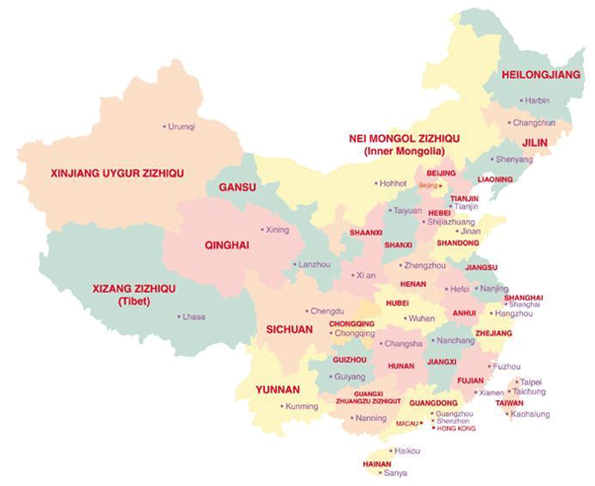

Starting in the 1980s, China's reform and opening up were initiated by the creation of the coastal special economic zones (SEZs), initially in the southern province of Guangdong, close to Hong Kong and Macao. Soon the reform extended from urban agglomerations such as Shenzhen and Guangzhou to other primary cities, from Beijing to Shanghai – thanks to the colossal investment projects in Pudong which turned the swampland into an emerging global financial hub.

During the past decade, the economic success of these megacities has been spilling over into other tiers of Chinese cities. Even before the onset of the global financial crisis, second-tier cities – such as Suzhou, Tianjin, Shenyang, Chengdu, Dalian and Chongqing – had already attracted significant attention with investments from global corporate giants.

At the same time, third-tier cities, from Ningbo and Fuzhou to Wuxi and Harbin, have been following in the footprints of first- and second-tier cities. Behind these three tiers of rapidly-growing urban agglomerations, there are still others such as Kunming and Hefei, seeking to take advantage of the urban growth trajectories.

Some 60 years ago, Lewis saw something similar in several developing countries, with their polar opposites, vibrant and modern cities, and sleepy and traditional rural villages. “There are one or two modern towns, with the finest architecture, water supplies, communications and the like, into which people drift from other towns and villages which might almost belong to another planet.”

Migration and the Turning Point

Paced by strong economic growth, China’s leading megapolises are also evolving very fast. The urbanization that took almost a century in the West is occurring in a decade or two in China. In 1979, Shenzhen was still a poor fishing village with some 20,000 inhabitants. In 2009, it had a population of 9 million, and income per capita exceeded $13,600, only $3,000 less than in Taiwan or South Korea. Now Shenzhen plans to achieve an average GDP per capita of $20,000 by 2015, the level of European countries, such as Portugal and Slovenia. In the latter, the real GDP growth will be more subdued in the coming years, at best. In Shenzhen and China’s other megacities, it will be around 10%.

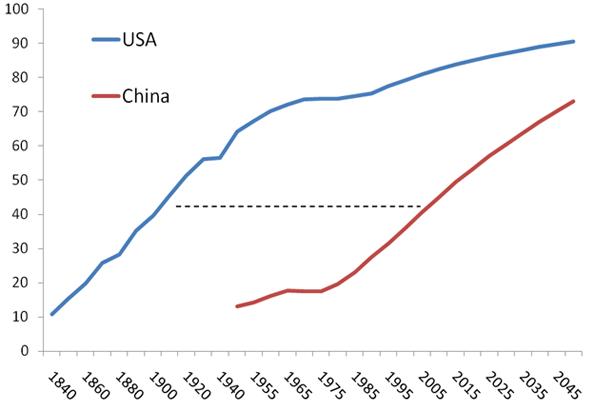

Yet, despite these colossal shifts, China’s urbanization still has a long way to go. In 1980, the U.S. urban population was 74% of the total; China’s comparable figure was only 19%. Today, America’s urban share of the population is more than 80%, whereas China’s remains less than 50%. Taken into consideration China’s colossal size and development level, this gap suggests extraordinary potential. In 2025, America will have two cities (New York and Los Angeles) with more than 10 million people, three with 5-10 million and 37 with more than a million. By then, China will have five cities with more than 10 million people, 9 with 5-10 million, and almost 130 with more than a million. Viewed this way, China’s urbanization has barely begun (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of Urban Population: United States and China

Winning China’s West

If Lewis had spent even some time in the rural China or the emerging new tiers of cities, he would have associated them with the world of “unlimited supply of labor”.

During the past three decades, migrant laborers have played a key role in China’s economic growth in the first-tier cities. Now as living costs rise fast in Beijing, Guangdong, and the Yangtze River Delta region, employment prospects are improving in the inland cities and the West.

Since the early 2000s, the new “Go West” policy covered the huge municipality of Chongqing, six provinces, from Gansu to Sichuan and Yunnan, and five autonomous regions. At the time, this region accounted for almost 30 percent of China’s population, but less than 17 percent of its GDP. Initially, the policy focused on the development of infrastructure (transport, hydropower plants, and energy and telecom establishments). But it is the new stage of development in eastern China that is now dramatically accelerating growth in the West.

Even before the global financial crisis, the Ministry of Commerce designated more than 30 “priority relocation destinations” in China’s inland to increase the share in the processing industry in central and western areas, especially in labor-intensive manufacturing.

In the future, China’s West hopes to catch up with its East through domestic consumption, cost advantage, investment policies and infrastructure, which has been boosted by the nation’s stimulus policies. China’s West is about to experience a revolution in durable consumer goods, from color TV sets to refrigerators. True, the volume of retail sales remains higher in China’s East, but sales growth is stronger in the non-coastal areas.

As costs have risen, China has lost some jobs to Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia, primarily for cheaper, labor-intensive goods like textiles, simple electronics, and toys. Yet, China’s West still offers many of the comparable benefits and an emerging infrastructure.

The Decades to Come

In the next two decades, China’s urbanization is expected to boost domestic demand by $4.5 trillion, which should assure a stable economic development even if exports decline. In effect, the urban migrants’ demand for housing is likely to become the largest driving force for China’s economic growth in the future.

During the past three decades, the share of China's city dwellers has more than doubled to 45 percent. And by 2040, the urbanization rate is expected to be close to 67 percent. In the next three decades, the number of China's urban residents is expected to grow by 360 million people to 970 million. In terms of current urban populations, this is the same as creating city space for entire urban America (260 million), Japan (85 million) and another 15 million people - within one generation.

This great transformation, however, is predicated on sustained economic growth and a stable international environment. China’s first-tier cities are now coping with the coming of the Lewisian turning point/ The big story in the coming decades, will be the takeoff in the west and among many once peripheral cities. Due to China’s sui generis magnitude, this process will take another decade or two.

Dan Steinbock is Research Director of International Business at India China and America Institute (USA), and Visiting Fellow at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China).

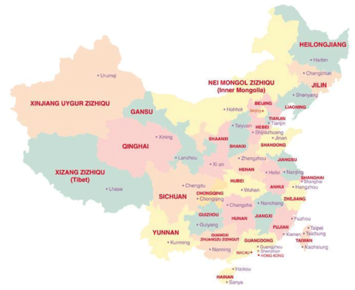

China’s Provinces and Cities

References

1 Hamlin, K. et al. (2010), “China Reaches Turning Point as Inflation Overtakes Labor,” Bloomberg News, June 11.

2 On the argument that China is coping with the Lewisian turning point, see Cai, Fang, Wang, Meiyan, 2008. A counterfactual analysis on unlimited surplus labor in rural China. China & World Economy 6 (1), 51–65.; Fang Cai, Meiyan Wang (2010), “Growth and structural changes in employment in transition China,” Journal of Comparative Economics 38 (2010) 71–81. On the argument that Lewisian turning point is years away, see Yang Yao (2010), “No, the Lewisian turning point has not yet arrived,” Economist, July 16, 2010; Roach, S. (2010), “ Chinese wage convergence has a long way to go,” Economist, July 18.

3 Lewis, W. Arthur (1954). “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor,” Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, Vol. 22, pp. 139-91

4 Steinbock, D. (2010),” Legacy of Globalization: Shanghai and Hong Kong as China’s Emerging Financial Hubs,” Policy Brief, Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, January 2010.

5 These tiers of cities are evolving dynamically and through a national plan. With its more than 31 million people, Chongqing, for instance, is already one of China’s five national central cities. National central cities have a great impact around the surrounding cities on integrating services in infrastructure, finance, public education, social welfare, sanitation, business licensing and urban planning.

6 In fact, Lewis’s classic article offers also another clue to assess China’s stages of growth. As far as he is concerned, small migrations explain little. In the 1950s, he noted, 100,000 Puerto Ricans emigrate to the United States every year. Still, it is Puerto Rican wages which are pulled up to the U.S. level. Mass immigration is quite a different kettle of fish. “If there were free immigration from India and China to the U.S.A., the wage level of the U.S.A. would certainly be pulled down towards the Indian and Chinese levels,” Lewis argued. In China’s economic development, the tens of millions of migrant workers have played the comparable role of pulling down the national wage level.

7 In the beginning of the “Go West” program, the largest proportion of the West’s total fixed asset investment was in infrastructure. And almost half of China’s huge stimulus of $586 billion was earmarked for transportation, infrastructure and power grids. These, in turn, facilitate the exploitation of minerals, natural gas and oil in China’s West. In addition to the stimulation of domestic demand, the government’s strategy is to “cultivate areas of high consumer demand and expand consumption in new areas”.

8 “China's urbanization to fuel domestic demand,” China Daily, November 15, 2010.

9 Steinbock, D. (2010), “Growth fueled by urban investment,” China Daily, February 25, 2010.

10 On the international relations dimensions of China’s stages of growth, see Steinbock, D. (2010), “China’s Next Stage of Growth: Reassessing U.S. Policy toward China,” American Foreign Policy Interests, No 6, December 2010.

potty training in 3 days

Infant Potty Training is both the name of a means of toilet training and the title of a book by author Laurie Boucke. The complete book title is Infant Potty Training: potty training in 3 days

fast vitiligo cure

It should be noted that whilst ordering papers for sale at paper writing service, you can get unkind attitude. fast vitiligo cure