By Richard Reep

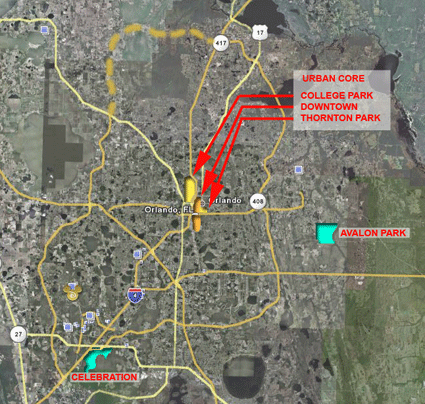

For the last decade the City of Orlando has been concentrating form, trying somehow to displace its image as the ultimate plastic city. Although tourism helped insulate Central Florida from the slowdowns of the 1970s and 1980s, the last three recessions hit Orlando harder than the national average. This metropolitan area has now been taking on a more essential task of morphing slowly away from its status as ephemeral support city for the theme parks.

One sign of this new appreciation for the basic necessity of good jobs can be seen in two new districts: one concentrated around medical research and practice; the other concentrated around digital media.

Both districts will greatly enhance the city’s core offering of service jobs, and are being nationally scrutinized for their viability as a new home for technological research and application. In the next phase of city-making, Orlando can make important steps towards a sustainable economy, if it grows good jobs while focusing on the basics of safety, security, and a spiritual core for its citizens.

Both districts will greatly enhance the city’s core offering of service jobs, and are being nationally scrutinized for their viability as a new home for technological research and application. In the next phase of city-making, Orlando can make important steps towards a sustainable economy, if it grows good jobs while focusing on the basics of safety, security, and a spiritual core for its citizens.

The first growth district, on Orlando’s ring road, is Lake Nona. Private interests have combined with institutions of higher education to create a core of medical research and technology. The most recent star addition to this, Nemours Children’s Hospital, will anchor part of the development. Medical research laboratories by Florida’s major public universities flank the hospital, and more medical facilities are on their way.

Surrounded by residential communities and scrub pine, the medical district is in its infancy. This community already boasts two promising features. For one, the focus on good jobs sets the fundamental stage for organic and meaningful growth created. This seems logical enough, but the employment element has been largely missing from most new developments of regional impact. Secondly, the residential community, currently less than 10% developed, appears to be growing unmolested by the need to conform to pre-set ideas about cities. Lake Nona’s Master Plan promises an 11-acre oval “town center”, likely to be a mixed-use district typical of recent Southeastern town centers: shops, offices, residential, and of course, the local supermarket, Publix.

Surrounded by residential communities and scrub pine, the medical district is in its infancy. This community already boasts two promising features. For one, the focus on good jobs sets the fundamental stage for organic and meaningful growth created. This seems logical enough, but the employment element has been largely missing from most new developments of regional impact. Secondly, the residential community, currently less than 10% developed, appears to be growing unmolested by the need to conform to pre-set ideas about cities. Lake Nona’s Master Plan promises an 11-acre oval “town center”, likely to be a mixed-use district typical of recent Southeastern town centers: shops, offices, residential, and of course, the local supermarket, Publix.

Thankfully, the developer is leaving the town center to the future, and this new core will have a chance to reflect Lake Nona’s mature identity, rather than be thrust upon the community by the Master Developer in some kind of bland neohistorical form. This is reminiscent of Valencia, planned in the late 1950s and developed in the 1960s, where core community functions such as hospitals, government offices, and schools were built first by the Newhall family near Los Angeles. Residential areas filled in the 1960’s and 1970s; but the original Town Center, designed by Victor Gruen, was not built until the late 1980s, after Valencia matured. The lesson of Valencia is that organic growth can yield a vibrant, successful development plan. Valencia remains today a positive addition to the Santa Clarita Valley and southern California in general.

Switch focus to the inner city: forgotten, chaotic, grim residences; sagging front porches and weedy lots. Orlando’s own inner city, Parramore, did not benefit very well from the run-up in the last six years, and by the looks on the faces of the residents who watch you as you drive by, they know it. The City of Orlando has decided that it is now their turn.

Switch focus to the inner city: forgotten, chaotic, grim residences; sagging front porches and weedy lots. Orlando’s own inner city, Parramore, did not benefit very well from the run-up in the last six years, and by the looks on the faces of the residents who watch you as you drive by, they know it. The City of Orlando has decided that it is now their turn.

This will be an interesting experiment to see whether the greenfield results of New Urbanism can be translated to what is essentially a classic, 1960s urban renewal project in reverse: Demolition of 20-year-old event center slums, to be replaced by new construction to further the cause of virtual reality.

The City’s bonding capacity, sadly, has been tapped for major venues (a new sports arena and a performing arts center), but failure of the event center has led to a healthy focus on higher skilled jobs. The city envisions a partnership with higher education and the private sector to create a digital media village, similar to Laval, a suburban community just north of Montreal. Laval, an existing neighborhood in search of new life, benefited from a similar effort when the city focused on developing its bioscience and information industries. Now Laval’s status has begun to show some basic street life and has a highly successful retail complex that draws shoppers from throughout the region.

This concept of a technopole has now been borrowed by the City of Orlando to create a similar district centered around digital media: movies, gaming, and other pursuits. The city must be careful to make sure that, like Laval, it concentrates on jobs growth first, and then seeks to integrate those jobs with the community. As a city with a strong, form-based planning outlook, Orlando will certainly be anxious that the Media Village conforms to the concepts of New Urbanism.

The trend is ominous: Cities that allow their job base to become concentrated in a small handful of industries are risking their economic lives on a set of very outdated assumptions. On the other hand, cities that have sought out high technology jobs have become the “survivors” of the economic downturn.

In the year 1980, there were only nine research parks in America. Today there are more than 200 in the United States, and competition from overseas is heating up fast.

It is important to remember what a giant head start that we gave to other cities. The Triangle Research Park near Raleigh / Durham was founded back in 1959, and now houses more than 150 research and technology companies. Although Orlando is the “new kid” on this particular block, if we focus on what the employers need, we still have a lot to offer besides tourism.

With the economy stagnating, a growing focus on jobs – and building an environment that promotes growth – should have a strong appeal. As in the 1930s, slower growth can begin to get the community to look beyond New Urbanist form-obsession and look to more fundamental elements that create jobs and wealth as opposed to seeking to win accolades from developers and the architectural and planning establishments.

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

Performing arts

In November, I finally went to an event at the Carr Auditorium and was surprised that it hadn't been torn down long ago. Has any progress been made toward placing the new facility in something other than a parking lot?