America’s cognitive elites and many media pundits believe high-density development will dominate the country’s future.

That could be so, but, if it is the case, also expect far fewer Americans — and far more rapid aging of the population.

This is a pattern seen throughout the world. In every major metropolitan area in the high-income world for which we found data — Tokyo, Seoul, London, Paris, Toronto, New York, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay area — inner-core total fertility rates are much lower than those in outer areas.

For example, inner London, notes demographer Wendell Cox, has a fertility rate of 1.6 children per female, which is well below the replacement rate of 2.1.

The total fertility rate is the average number of children born to women between 15 and 44 years old. In the outer reaches of London, this rate hits 2.0, one-fourth higher.

In Sydney, Australia, where increasing population density is a sworn goal of planners, the inner city now has a fertility rate of 0.76, compared to 2.0 or more in the outer suburbs.

Nowhere is the confluence of high density and high prices more evident than East Asia. This region is now home to some of the lowest fertility rates on Earth.

Take Seoul, South Korea, a paragon of high-density development where high-rise buildings dominate even on the periphery.

Seoul’s fertility rate is about 1.2, similar to rates found in Tokyo, Singapore and Hong Kong. This is the kind of place urban planners often cite as a role model.

A recent glowing report in Smithsonian Magazine heralded Seoul as “the city of the future.” Architects, naturally, join the chorus. In 2010, the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design named Seoul the “world design capital.”

Yet the real frontier of ultra-low fertility may now be coastal China. Both Shanghai and Beijing have fertility rates of roughly 0.7, almost one-third of the replacement rate. Overall, China’s cities have a fertility rate under 0.9.

Gavin Jones, a leading demographer of Asia, suggests that despite recent easing of China’s one-child policy, the world’s second leading economic power is experiencing a dramatic slowdown in its birthrate.

In places such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tokyo and Singapore, more than one-quarter of women will never marry and even more will never have children.

The result, Jones suggests, will be a society made up increasingly of single people, one-child families and very old people.

In less than four decades, according to United Nations projections, Japan will have more people over 80 than under 15.

This may present more of a challenge to Japan in the future, one professor suggests, than the rise of China. Indeed, over time, notes Jones, the same process will be seen across East Asia, as well as parts of Europe, as the anti-marriage and post-familial trends accelerate.

“This won’t get better in the future,” he suggests. “The decline is just starting and it’s expanding to other areas, and the process seems inexorable.”

For now, America, with a fertility rate of 1.89, stands in somewhat less distress, but that could be changed by increasing urban density — the very policy widely adopted by pundits and planners and broadly endorsed by urban developers.

As Cox has shown, localities with higher densities and higher prices — the two are often coincident — have considerably lower birth rates than areas with lower prices.

This becomes even more evident when one considers the segment of the population between 5 and 14 years old, when children enter school.

In 2012, urban areas with the highest percentage of children are predominately lower density and lower cost, including Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Riverside-San Bernardino, Atlanta, and Phoenix.

Urban areas with the lowest percentage of people in these age groups were also the New Urbanist exemplars, such as Boston, San Francisco, New York, and Seattle.

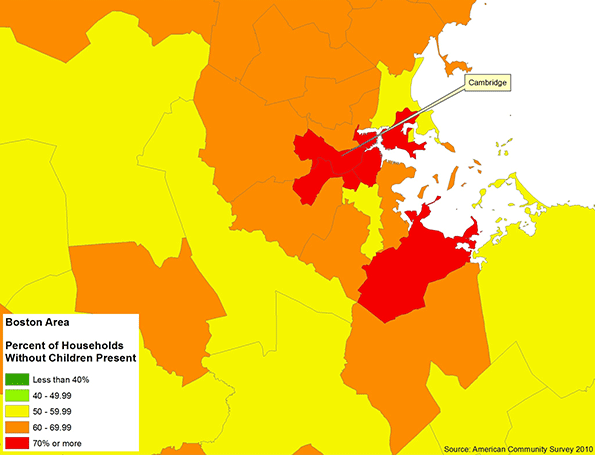

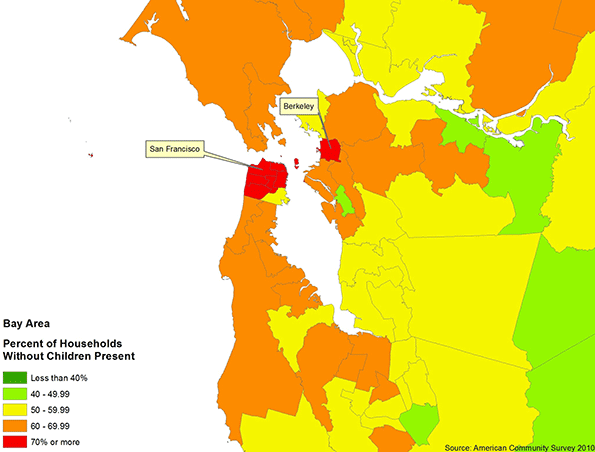

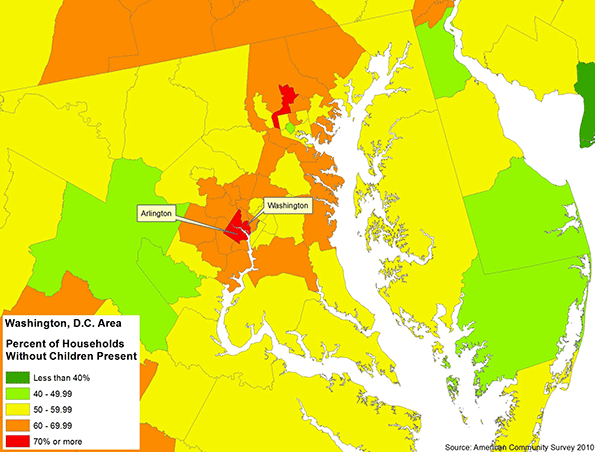

The geographical nature of low fertility becomes even more clear in maps developed by demographer Ali Modarres.

These maps show the percentage of households without children present. In regions such as New York, San Francisco, Seattle, D.C. and Chicago, the message is clear: much lower fertility rates in the denser urban cores.

Maps Source: Demographer Ali Modarres, chair of urban studies at the University of Washington at Tacoma, using data from U.S. Census American Community Survey 2010

In virtually every case, family size expands the closer one gets to the periphery; in contrast, some of the inner rings show fertility rates that approximate those seen in the hyper-dense Asian regions.

What this suggests is that a continued focus on forcing Americans to abandon their suburban lifestyles will have a profound impact on the nation's future competitiveness.

An aging America will lose much of its current advantage in terms of vitality of our markets and labor force, and will be forced, like many East Asian and European countries, to invest ever more resources to take care of an aging population.

Yet don’t expect this to affect the planners, environmentalists and their allies in real estate development, who hope to harvest windfall profits by urging and even forcing people to embrace high-density living.

Their gain will not be to America’s advantage and will consign future generations to persistent slow growth, greater debt and a kind of societal malaise as the family fades in the face of ever greater emphasis on individualism.

At the same time, an expanded state will be needed to keep the old folks alive in the absence of traditional networks of children and relatives.

This piece originally appeared at The Washington Examiner.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available for pre-order at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Crossing the street photo by Bigstock.

Hi I found your site by

Hi I found your site by mistake when i was searching yahoo for this acne issue, I must say your site is really helpful I also love the design, its amazing!. I don’t have the time at the moment to fully read your site but I have bookmarked it and also add your RSS feeds. I will be back in a day or two. thanks for a great site.

girlsdoporn

Maybe

It would be interesting to tease out what proportion of urban core fertility rate drops are caused by being in the urban core (people who would have more children were they removed to less dense housing) and which are self-selecting (people who chose to live in the urban core for reasons that are consistent with small family size). Having lived everywhere from Capitol Hill to the grasslands of Tibet- I've seen people making complex decisions about where to live and whether/when/how many children to have based on a number of factors. Many people I've met, including myself, choose to live in the urban core at times where family size is small,and relocate to less dense areas when family size grows and economic conditions allow. Many of us would have remained in the urban core, or would have never left the farm regardless of family size if economic conditions (jobs versus cost of living) were right. So there could be more here than one direct line of causality for falling fertility rates. It would be interesting to trace the fertility rates of those who have left Seoul, Hong Kong, and urbanized eastern China to settle in far less dense areas of North America.

Secondly, the field of planning may do well to further consider how to move from growth orientation to management of steady-state or even shrinking populations. If populations are ageing and shrinking, this is not necessarily a normative problem to be avoided, it is a resource management and policy issue to provide innovation and flexibility in infrastructure, services, and immigration to build the highest quality of life with the lowest environmental and equity impacts.

we have variation among regions

We do, at least, have variation among the states or even regions within states, save to the extent that the states themselves may force dense development on communities that may be more inclined to allow development of single family homes. Oklahoma City or San Antonio are release valves to some extent for policies promulgated in the San Francisco Bay Area by ABAG who envision that fully half of all new homes will be dense,deed restricted affordable units. One does not have to spend much time around planning authorities to realize that they consider the construction of any new single family home to be a defeat.

However, for those of us who already own one in these areas, we can probably count on them continuing to increase in value for some years to come, and that is a source of political support for the planners (until at such point as young minorities come to realize that it "them" the planners are talking about when they say "we" need to live in a more dense environment.)

The difference between "necessity" and discretionary choice

I suggest that there is a disturbing correlation in the data, between high-density living as a matter of necessity rather than choice, and national demographic collapse.

At least in many of the western world's cities, there are other options for people who want to have a family, and they are not deprived of the discretionary income to make that choice. The correlation between dense areas and low birthrates is at least not "the whole story" for the national economy in those cases.

Joel is right that urban planners are hell-bent on changing this paradigm. Many of them, if you scratch their surface, will be found to hate human procreation anyway.

Even if they claim to be in favour of "housing choice", the effect of "compact city" policies on housing costs means that people are in fact deprived of choice. It would be absurd to argue that the small space per person that people in the UK, Japan and China put up with, is a matter of "choice", given the proportion of their income swallowed by the cost of the small amount of space they do occupy.

There is no high density city with living that is "affordable" in the sense that actual family homes are "affordable" in US cities that are free to grow at low densities. So it is as much a matter of lack of discretionary income as it is lack of space. One of the biggest lies from the "compact city" advocates is that "affordable housing" is a realistic part of their plans. In reality, the cost always goes up even as the size and quality falls.