Home-made housing (left): Refugee families from Mindanao set up shop-houses in the grounds of the mosque in Quiapo. Quiapo contains a number of significant sacred sites for Catholic pilgrimages and festivals. Islamic refugees are making a living in the markets, even as some have sought refuge inside their own sacred site.

Private turned public (above): Stylish home design transformed into gallery space showing contemporary Pinoy artworks. Pinto Art Gallery, Antipolo.

Modernizing the canal frontage: A Spanish-era esterogets a make-over Chinatown style. The water is polluted, the smells are noxious and the blank wall opposite and infor- mal housing at the back compromise the attempt at a waterfront outdoor sitting area.

The air-con city: Mega-malls and new skyscraper districts such as these in Pasig City (Ortigas) provide havens from the outside world of heavy metals – in the air and on the tollways. The lack of commons means that the corpora- tized spaces of malls, and gated apartment and business high-rises, are very popular not least because these cathedrals of consumption are air-con simula- cra of public life. Mega-malls are not only about the shopping but also about looking, promenading and hanging out. But these are not public spaces so much as corporately owned.

Informal housing on an estero, Quiapo: Public space is non-owned space and therefore represents what is left over rather than something consciously created to reflect public order and culture. Without adequate sanitation systems the water- ways do the flushing, but modern cities generate more than organic waste so the esteros have long been biologically dead. The poor are ever ingenious in making the best out of whatever comes to hand – in recycling building materials for their homes, parking their bicycles on the public bridge, hanging the washing over the canal, and creating walled gardens.

Superguard at your service: In a city of gates and borders that mark the boundaries of private territories, private armies are required by rich and poor alike to police them. Uniforms and guns abound and it is not always obvious who is protecting whom. Regulation and authorization of the guardians is a complex, semi-legal and irregular process. Each guard has his own moniker, many of them spoofs of popular culture super-heroes.

Mega-mall commons: Shopping malls are owned by billionaire tycoons with dynasties like the Araneta, Ayala and Sy families. Local pop and film stars perform on concert stages in the cathedral-like vaults of the central halls where fashion shows, trade fairs and church masses are also held every day. Araneta Center, Cubao, where this photo was taken, is one of the earliest popular mall areas in Manila, dating back to the 1950s, that is undergoing a major make-over. Its fortunes declined into the ’80s as the attentions of the fashion-conscious middle class moved to other malled cities. For the past two decades, Cubao has been a shopping centre for the poor and a bus terminus for the provinces. The area itself has been notable for its urban grunge. The sex bars were shifted from Ermita and Malate to Cubao in the ’90s. The shopping mall has recently had a major make-over and is now connected to two light rail lines – a development that in turn attracts high-density apartment building in the area. As Cubao begins a gentri- fication process, so its urban rents rise. The rich return – or at least a new middle class arrives to graze, shop and parade. The Araneta Center and Coliseum complex has over a million visitors daily.

New urban villages arrive in Manila: Fort Bonifacio is the biggest, boldest experiment in new city building inside a Southeast Asian mega-city. As a series of public-private partnerships, it represents a sustained attempt to mimic world’s best practice in city building and urban renewal. Here at Serendra the pedestrian mall exhibits a careful integration of greenery, sitting areas, promenades, and restau- rants, cafes, boutiques and medium-density walk-up apartments. Not surprisingly, it is very popular and is copied by developers of other new cities in Metro Manila. It is one thing to get the plan right, quite another to regulate and maintain these areas in a city of massive socio-economic inequalities.

High wall to the street: The rich build fashionable mansions with global-local consciousness of design fashions. Even if the suburb is not gated, the fence to the street is – more often than not – high. The formula is something like this: the more aspirational and richer the houseowner, the greater the probability that the sociality is turned indoors and against the street. The rationalization is security.

SM Marikina: shopping mall as fortress: Waterfront park on the Pasig River replete with sculpted carabao. The people’s park project has been embraced by the citizens of Marakina Barangay, but here SM presents a blank wall and car park to the riverfront and thereby discourages pedestrian flows between the shops and the park.

Skyscraper city: Ortigas, Pasig City, is a poorly planned new city along EDSA. Identi-kit skyscrapers sit cheek to jowl, there are no parks, and the streets are car-jammed 24-7.

Drain as moat: The gated community of Casa Verde has three defensive layers to the street – the walls of the houses themselves, the drain which acts as a moat, and a wall on the street. The opposite side of the street is likewise walled. It is a street without pedestrians – an unusual phenomenon in Asian urbanism.

Theme park cities: Las Vegas is most famous for this kind of ersatz ‘Dis- neyfication’ of living spaces, but Manila has been doing it for longer – theme park histories of imagined communities in medieval and Renaissance Europe abound. The aesthetic might be kitsch but the lived experience for the local residents and business folk is another thing altogether. In a city with one of the lowest percen- tages of green and pedestrianized spaces, these places – such as this one in McKinley Hill, Fort Bonifacio – are highly sought after and valued by its citizens.

Spectres and spectacles: New apartment blocks in Fort Bonifacio tower over the hauntingly beautiful memorial park and cemetery for 17,201 American military killed during ‘the liberation (sic) of Manila’ and other parts of the Philippine archipelago. It is the largest such Second World War cemetery for American military in the world, covering 152 acres. They have the best views and sea breezes in Manila.

Tampa Bay, Florida, or Cairns, Australia? No, it’s Fort Bonifacio, Manila. Fort Bonifacio was made possible by Mt Pinatubo blowing its top on 15 June 1991. No amount of protests against the US communications and military bases in the Philippines could budge the Americans. But the fall of the Soviet empire and a volcano did the trick. Fort Bonifacio, ironically, named by the Americans after one of the revolutionary leaders against the Spanish colonisers, when vacated, left one of the largest areas ever made available for urban renewal in an Asian city. It is now one of the highest social status new areas and consequently one of the most expensive. Its progress has been slow, not least due to various economic downturns but also because of the care taken by government planners and corporate investors in designing the infrastructure of a city that integrates commercial, government, and social facilities and amenities. In stark contrast to the big boxed mega-malls, this shopping area seeks a suburban outdoor tropical ambience, and again privi- leges pedestrians over vehicles – a too rare occurrence in Manila.

Gates, guards and wires: Manila is a world leader in gated community living. This one in Cubao is typical in its structure – two-storey, semi-detached houses inside a fortress wall with single gate entrance with 24-7 security guards. Standard issue telephone lines clutter the streetscapes of cities the world over – will Wifi technologies clear urban skies?

Quiapo, Manila: How can a city turn a backyard sewer into a living waterfront again? The canals (esteros) of Manila are historical artefacts of the Spanish era, but are now the backyards of the poor. The challenge is threefold: heritage (historical con- servation and re-use), ecology (toxic and organic waste management, restoring riv- erine and estuarine ecosystems requiring an integrated approach to the whole Pasig River and Manila Bay area and not just the canals themselves), and livelihoods and sustainable housing for the poor (including their involvement in the re-development of the area and the restoration of the canals). Some success on all three fronts can not only transform the economic fortunes of the whole city but make the area an urban village area that is aesthetically appealing to locals and tourists alike.

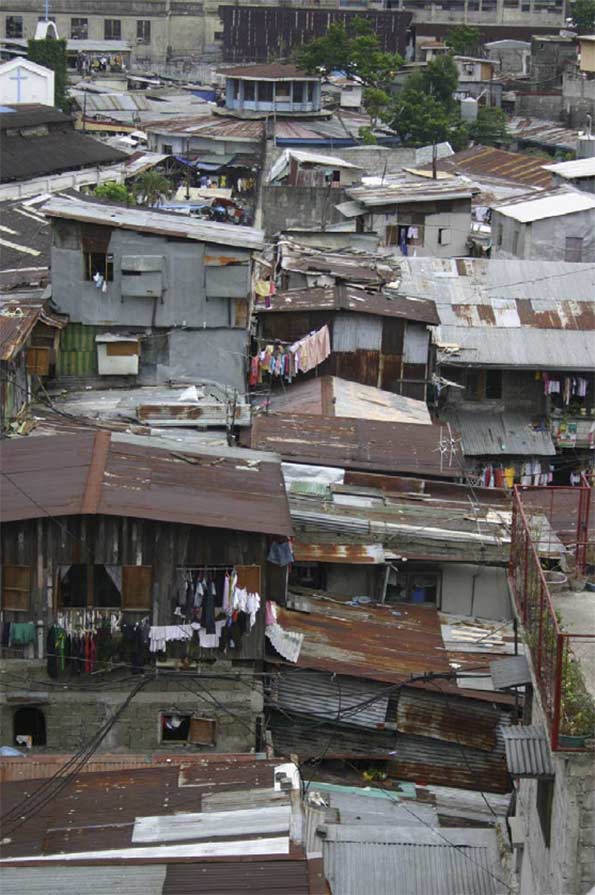

Spot the prison wall!: This high-density informal settlement in the university belt area opposite Far Eastern University fences in a prison! You can spot the panopti- con guard house at the centre-top of the photo. This community is well-established but has been legally protesting a developer’s permit to build a shopping mall on their site. Informal settlers use every available space and the streets and paths are literally left-over space. The more established, longer-term settlers build up and consolidate their homes by turning their walls from cardboard, Masonite and plas- tic into concrete bricks and tin roofs. By definition informal settlements are DIY – including sanitation, water, electricity and telephone connections. The high density ensures maximization of population in an inner city zone and makes it easier for its residents to organize protection against potential hostile intruders. The disadvantage is that should there be a fire or flood then fast and efficient assistance by city services is hard to provide.

Intramuros: The old wall and the new moat: Intra-muros is the original walled city of Manila, and now the old Spanish moat – that was filled in by the Americans in the name of public health – has a new purpose: golf! Along with polo and yachting, golf is a high status sporting pastime which the very rich can use to assert their distinction. In a city where over 50 per cent are poor and which has one of the lowest proportions of areas allocated to public parks in the world, here is a key public space that has been turned into a private space for those rich enough to afford leisure time and who can pay for the privilege.

This piece was originally published by Sage Publications Thesis Eleven, 112, October: 35-50.

Trevor Hogan teaches in Sociology at the School of Social Sciences, La Trobe University, where he is Deputy Director of the Thesis Eleven Centre for Cultural Sociology and Director of the Philippines-Australia Studies Centre.

Caleb J. Hogan is a Fine Arts student at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University (RMIT).