“No man needs sympathy because he has to work, because he has a burden to carry,” began Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. president from 1901 to 1910. “Far and away the best prize that life offers is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.”

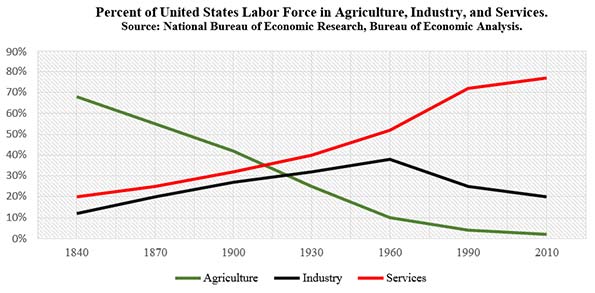

No doubt, during Roosevelt’s time there was much work to do. In 1910, for example, nearly 40% of the country was still employed in agriculture. The percent of workers in industry—or manufacturing, construction, and mining—was at 30% and rising, driven by the revving of the Industrial Revolution.

So, 70% of the country’s workforce made a living through labor. They made food to eat and the steel, railroads, cars, bridges, and buildings that modernized America.

Cleveland was a prime benefactor. The manufacturing sector alone employed nearly 307,000 Clevelanders by 1967.

But things changed. Labor-intensive industries matured, which ultimately means taking less people to produce more output. The percentage of the American labor force employed in agriculture stands at 2%, down from nearly 70% in 1840. This doesn’t mean we eat less food, but that technological advances have made the food sector ultra-efficient.

Industry has been experiencing the same forces. Twenty percent of Americans are employed in manufacturing, mining, and construction. In the manufacturing sector, the national percentage is 8%, with Cleveland at 12%—down from 21% in 1990. Again, this doesn’t mean we don’t manufacture things— manufacturing output is at an all-time high nationally—it’s just that we need fewer people to produce more goods.

Okay, so where do people work? The simple answer is services, or those sectors that make up the economy outside of agriculture and industry. Think legal, marketing, business, technology, education, healthcare, and hospitality. For instance, 20% of the nation worked in services in 1840. By 1960 that number was over 50%, before reaching nearly 80% by 2010.

These numbers illustrate a shift in the U.S. economy over time, or from goods producing to service providing. To a large extent, these services are based on the production of ideas.

Writing in the Harvard Business Review, the University of Toronto’s Roger Martin dubs this change the “rise of the talent economy”. Martin notes that in the 1960s, 72% of the top 50 U.S. companies owed their wealth to “the control and exploitation of natural resources.” Today, however, only 10% of the nation’s top companies are industry-based. Instead, over 50% of America’s companies are talent-based, such as Google, Apple, and Microsoft.

“Over the past 50 years the U.S. economy has shifted decisively from financing the exploitation of natural resources to making the most of human talent,” writes Martin.

Enter Silicon Valley. As Pittsburgh was to steel and Detroit to cars, Silicon Valley has been to the talent economy, particularly technology. It was there that the top minds clustered to design new-age circuits and microprocessors in the 1950s and 60s. It was also there that the best software engineers went to birth the internet, search engine, and social media in the 1990s and 2000s.

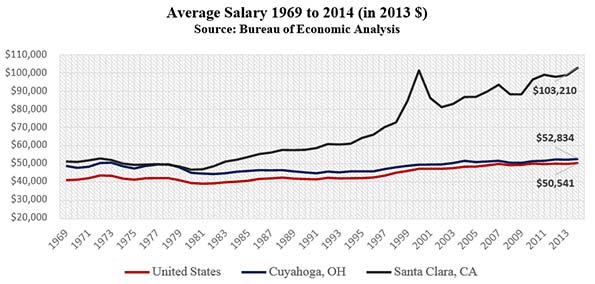

On the backs of this talent came the wealth, not only the venture capital that has continually acted to “water” the region’s innovation, but also the rising wages of the workers. In fact, in Santa Clara, C.A., the county seat of Silicon Valley, the average salaried employee makes over $103,000 annually, approximately double that of Cuyahoga County employees and the U.S. workforce as a whole.

The successes of Silicon Valley have led many regions to devise their own strategy to be a technology hub. Simply, there existed an “old” economy, so how does a region transition into the “new” economy, primarily one embodied by the high-end services and start-up culture of Northern California?

Often, the tactics are rudimentary, like branding a part of your region as “Silicon X” so as to attract the components of a tech cluster. For instance, Philadelphia has “Philicon Valley” and New York has “Silicon Alley”, whereas New Orleans has “Silicon Bayou” and Portland has “Silicon Forest”. There’s “Silicon Swamp” in Gainesville, “Silicon Slopes” in Utah, “Silicon Harbor” in Charleston, and a variant of “Silicon Prairie” in Dallas, Chicago, Omaha, and Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Then, once you brand a part of your region “Silicon X”, the next step is to get the story out. A recent piece in Charleston Magazine entitled “The Rise of Silicon Harbor” is illustrative on this front. The author opens the piece by explaining that in Charleston there are “three local tech companies, all within three miles of each other”. The author then quotes a media outlet that states Charleston’s “Silicon Harbor is on its way to becoming the East Coast counterpart to California’s Silicon Valley”.

This idea that your region can become the “next Silicon Valley”, well, its clickbait for online journalism—if only because folks wantto believe their hometown is the place of the future.

For example, a recent Huffington Post piece hints “You Might Be Living in the Next Silicon Valley”. “Could Detroit become the next Silicon Valley?” echoes the industry magazine CIO. Meanwhile, a NewYorker piece is titled “How Utah Became the Next Silicon Valley”, while an Oklahoma story is headlined “Vision proposal aims at Tulsa being the next Silicon Valley”.

Still, if everywhere is the next Silicon Valley, then nowhere is the next Silicon Valley. That’s the reality, and it’s important for cities to grasp it so they can plan their economic futures properly.

“When it comes to tech, nobody can simply create the next Silicon Valley,” explains Aaron Renn, a Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

“Just because a place has a number of startups doesn't mean it's destined to be a Silicon Valley,” Renn continued. “By all means celebrate a growing tech industry, but don't get carried away.”

But the bigger issue for regions looking for their economic future in Silicon Valley’s past is whether or not that’s even a sound strategy in the first place. Specifically, the tech economy is also a maturing, prone to the same job contractions, offshoring, and wage declines that hallmarked deindustrialization.

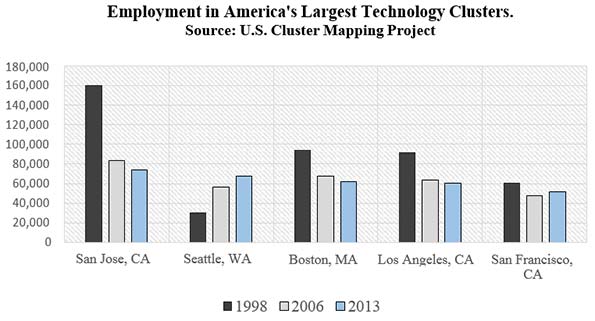

According to data compiled by the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, four out of the top five tech clusters in the United States lost jobs from 1998 to 2013. San Jose, CA, the metropolitan area comprising Silicon Valley, led the way in contraction, going from nearly 160,000 tech jobs in 1998 to fewer than 74,000 in 2013—a decline of 54%. Telling, automotive employment in Detroit declined by less over the same time period, at 32%.

These figures are in line with a new study out of Oxford University that found that while technology start- ups often create a lot of wealth, they are not good at creating many jobs. The study found that only 0.5% of the American workforce in 2010 were employed in industries that did not exist in 2000.

“What I think the Oxford study is saying is that you’re not getting the kind of job growth from these kind of high-tech, high-growth, high-profitability startups that you had in the past,” said economist Jim Pethokoukis in the industry magazine Re/code.

Why? A primary culprit is that tech jobs are becoming automated, just like farm and factory jobs before it. Specifically, tech companies over the last 15 years don’t need to hire as many people as they did in the 90’s because the software — loosely described as machines — is doing the work.

For Jim Russell, the economic development blogger at Pacific Standard, the aging of the tech industry— Russell uses the term “tech convergence”—has echoes in the decline of industry. Russell discusses his life growing up on the run from macroeconomics, going from Erie, PA, to Schenectady, NY, to Vermont as his father, a General Electric engineer, tried to keep ahead of the wave of contractions.

“He had an uncanny knack for moving our family just before the layoffs hit,” said Russell. “We were always racing to stay ahead of the economic restructuring.”

Russell, whose wife is in tech sales, is experiencing the same game of cat and mouse today.

“The tech industry enjoyed divergence until the end of the 1990s,” he’d note, explaining there were “fatter” times in emerging tech hubs like Boulder—where they’d lived.

“But then the bubble burst,” Russell explained, “resulting in massive layoffs. Good friends were out of work.”

Today, his family lives in Northern Virginia. That’s because it makes no economic sense for firms to house tech sales in Silicon Valley. This is partly due to the exorbitant cost of living in Northern California. But it is also due to the emergence of cloud computing, which has pushed tech everywhere— meaning tech hubs are increasingly nowhere.

This maturation of tech has Russell wondering “whether Silicon Valley is the next Detroit”.

Does this mean technology is no longer integral in regional economic growth? No. It just means the tech industry is changing. Detailing this change can both sharpen, if not make more realistic, a regional innovation strategy.

According to the Manhattan Institute’s Aaron Renn, the issues boils down to this: “Do you have proprietary industry to marry to tech?”

What Renn is getting at is the fact that tech in itself is a tool. It is by and large circuitry that allows access to information. But information is not knowledge. To give an example, information is the medical textbook, while knowledge is the application of information to become a heart surgeon. In other words, in what fields of applied knowledge can technology be tied to so as to further a given regional industry?

Most recently, tech has been tied to the entertainment or leisure industry. “Silicon Valley started with tech for the sake of tech: making computers, search engines, and software,” says Cleveland technologist Eamon Johnson. “Now it's 20-something dudes making solutions to replace what their mom did for them at home…laundry, food, rides around town, and recommendations on where to eat.”

According to Johnson, the coming evolution of innovation is to use the next generation of computing power to go beyond tech’s capacity to distract or consume.

“But techies need industry experts to give them problems so solutions can be worked on,” he says.

This exactly what is happening in Cleveland with healthcare. Cleveland observes, treats, and innovates within the field human health like few other regions worldwide. As a result, the field of medical technology, or medtech, is gaining some traction in the region.

This is evidenced by IBM’s recent acquisition of the Cleveland Clinic-spinoff Explorys, which is a “big data” health analytics firm. The company, based in Cleveland’s University Circle, is expanding its Cleveland office, perfecting its processes of how the region’s elite health “know-how” can be further mined through technology—thus creating more knowledge, and then more health innovation.

These kind of developments are important. Medtech is still a frontier industry, and it fits in well with Cleveland’s area of specialization. So there’s plenty of room for a first mover advantage if the region can gets its medtech playbook right.

Now, is medtech cool? Well that depends on your definition of “cool”. "You can work for a cool tech company with a texting app," said Explorys’ Charlie Lougheed to the Plain Dealer recently. "Or you can work for a company that improves health for millions of people."

Returning to Teddy Roosevelt: that is a lot of work, and a lot of work worth doing.

Richey Piiparinen is a Senior Research Associate who leads the Center for Population Dynamics at the Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University. His work focuses on regional economic development and urban revitalization.