The rising cost of entitlements will test inter-generational harmony.

In the week following the Brexit vote, a recurrent complaint from the losing side was that a majority of older people voted to leave while a majority of younger people voted to remain. In the eyes of the complainers, this rendered the leave outcome less legitimate because younger people have more years of life ahead of them and therefore would allegedly suffer more than old people from a decision to leave the European Union. So much for the wisdom of old age knowing what is best. And so much for the principle of one person one vote, regardless of age, gender or race or whatever.

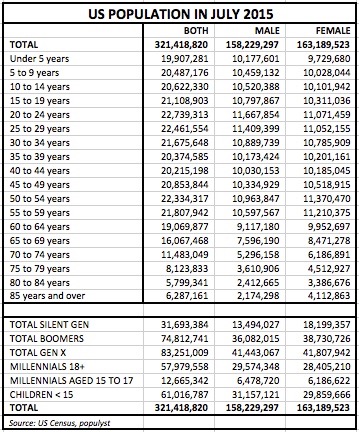

Instead of disenfranchising a group of older voters, we may consider allowing children some representation in our voting system. In the United States, the voting age is 18 which means that there are approximately 74 million US citizens aged under 18 who do not have the right to vote. That is a sizable 23% of the entire population who will all be adults by 2034 and who may not in the future take kindly to the long-duration budget commitments that were made in their absence.

Entitlements Demand and Supply

When Social Security was introduced in 1935, US life expectancy at birth was 62 years. When Medicare was introduced in 1965, it was 74 years. Today, it is approaching 80 years. What is more, people who are now middle-aged or older can expect to live past the age of 80. Life expectancy at birth is 80 years, but an American aged 70 can now expect to live to 85. And one aged 80 can expect to live to 89. Meanwhile the retirement age has remained around 65 since 1935, which means that the demand for these entitlements has increased in line with or faster than the rise in life expectancy.

In recent years, two other factors have put this demand on an accelerating trajectory. One is the rising number of retired baby boomers. The other is the relentless increase in health care costs.

On the other side of the equation, US households have fewer children today than in the past. The US Total Fertility Ratio (TFR) was a low 2.0 children per woman in the mid 1930s due to the Great Depression. It then zoomed to 3.5 at the height of the baby boom in the late 1950s before settling back back to 3.0 in the mid 1960s. But today, the TFR is back to its Depression era levels of 2.0 children per woman. It is a cruel irony that Medicare was enacted in 1965, just as the baby boom was ending. Because there are fewer workers per retiree today, the supply of dollars for entitlements has become less abundant.

Pros and Cons

Going back now to the question of the children’s vote, there are at least two reasons to maintain the status quo, which is a right to vote at 18.

First you could say that before a certain age, a person is not mentally equipped to make a critical choice between several candidates. Some people may argue, and not just for comic effect, that many adults from any demographic group are similarly ill-equipped, but that is a more subjective appraisal.

Perhaps this question is better addressed by re-examining what the voting age should be. Is 18 the proper age to get the right to vote? It would not be hard to make a case that 16 is old enough. If you can drive, you can vote.

Second you could say that young people should not have the right to vote because they don’t pay taxes. But as we know, a large percentage of adult Americans also don’t pay taxes. If there is a case for eliminating representation without taxation, there is no reason why this restriction should be confined to the under 18 cohorts.

On the other side of the argument, the logic of giving children some representation would be obvious if we hadn’t lived without it for so long. For one, it would place a check on government actions and decisions that create economic benefits for older generations while imposing a financial burden on the young. If the very young had some representation, the magnitude of this wealth transfer would certainly be smaller.

Two Steps for Representation

In theory, Americans aged less than 18 are represented indirectly by their parents’ votes. But in practice, the idea that a teenager would agree with his parents’ political choices sounds realistic only to someone who has never met a teenager. Therefore Step One would be to provide some representation by lowering the voting age to 16.

That would still leave 66 million Americans aged 0 to 15 with no direct representation. Today, a family of two parents and three children has two votes. But a childless couple also has two votes. We may then consider Step Two which is to give parents a fractional vote for every child. For example, a family would get an additional one third of a vote if the family has one child, two thirds for two children and one full vote for three or more children. The extra fractions would be attached to one of the parents’ votes. So if that parent pulled the lever for a certain candidate, his vote would count not as one vote, but as 1.33 votes if he has one child, 1.67 votes if he has two and two votes if he has three or more.

Of course, this could get complicated quickly if the parents disagree on whom to vote for. Which parent would become the custodian of the fractional votes to use on Election Day? This can easily be addressed by having parents take turns at every new electoral cycle, by having the fractional votes randomly allocated to either parent, or by giving each parent half of the fractional votes. In the latter case, for a family with three children, Mom and Dad would each have 1.5 votes.

Yet another proposal is to let each child decide his/her vote and to allocate to him/her a fractional vote that starts at one tenth of a vote at the age of nine and grows by one tenth every year until it reaches a full vote at eighteen. In this case, a ten year old would have 2/10 of a vote and a fifteen year old would have 7/10 of a vote and both would choose their own candidates instead of piggybacking their parents’ preferences.

As things stand today, giving children some representation would tip the scale to the Democrat candidate in many contests. In the most recent election for example, Pew Research estimates that voters aged 18 to 29 favored Hillary Clinton by an 18% margin and those aged 30 to 44 favored her by 8%. Meanwhile, voters aged 45 or higher preferred Donald Trump by an 8% margin.

Notwithstanding probable resistance from some quarters, the issue ought to be decided on its own merits rather than on whether it helps or hurts one or the other party. If one party’s platform appeals mainly to the older generations, the children’s vote would be a healthy jolt and an incentive for that party to start addressing issues that are of greater import to the young.

Further, any concern that children representation would skew the results unfairly is mitigated by the fact that, in a typical election, as many as 45% of eligible voters don’t even bother to show up. Because the margin of victory is small in most elections, a low turnout also leads to a skewed outcome.

Sami Karam is the founder and editor of populyst.net and the creator of the populyst index™. populyst is about innovation, demography and society. Before populyst, he was the founder and manager of the Seven Global funds and a fund manager at leading asset managers in Boston and New York. In addition to a finance MBA from the Wharton School, he holds a Master's in Civil Engineering from Cornell and a Bachelor of Architecture from UT Austin.