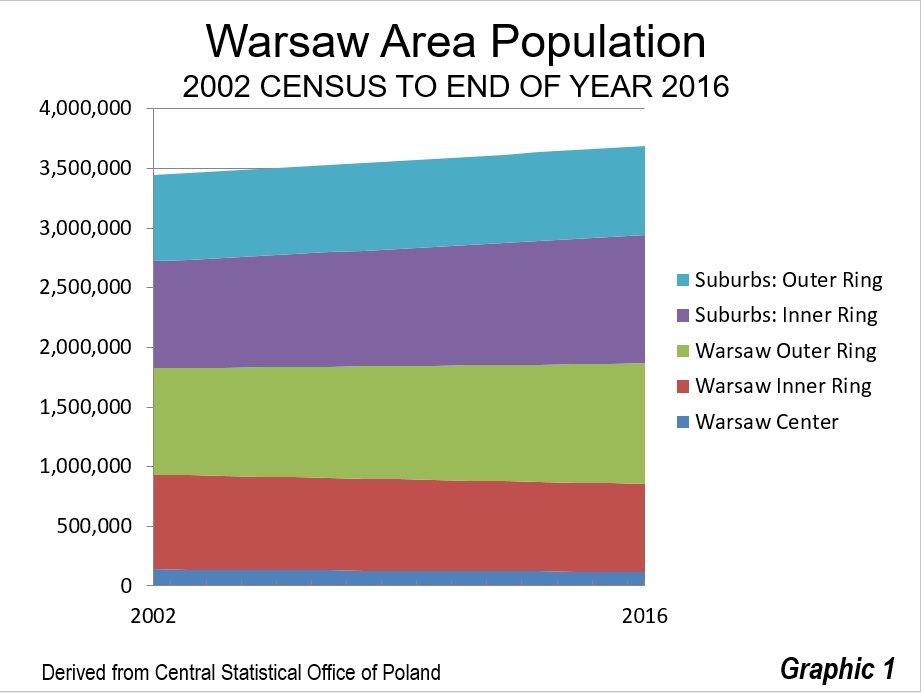

Like other major cities in the high income world, Warsaw has seen central area population losses, with all of the population growth taking place outside the urban core, principally in the suburbs and exurbs (Graphic 1). The city's districts were reconfigured so that direct comparisons cannot be made before the 2002 census.

The Warsaw region consists of the city of Warsaw, a county-level national jurisdiction (powiat) and seven powiats in the suburbs and nine in the exurbs. The Warsaw region grew from 3.31 million residents in 2002 to 3.58 million in 2016, a 0.5 percent annual growth rate. Warsaw's slow growth is substantially faster than that of the nation, which has not gained in population since 2002, both as a result of a below-replacement fertility rate and migration to other parts of Europe.

The Central District

The central district (Śródmieście), which includes the central business district (CBD) and the central railway station (Warszawa Centralna) experienced a loss in population of 14 percent from the 2002 census to 2016, according to the Central Statistical Office of Poland.

The skyline of Warsaw (Graphic 2) used to be dominated by the Palace of Culture and Science, which was constructed as a "gift" to the Polish people from Soviet leader Josef Stalin in the early 1950s (though completed after his death). It is sometimes called the "Eighth Sister," referring to its similarity to the "seven sisters" in Moscow that share a very similar "wedding cake" design. Like Moscow State University and Ukraina Hotel buildings in the Russian capital, the Palace of Culture and Science is fully symmetric from the base up. The Palace is located at the very center of Warsaw, adjacent to Warszawa Centralna and even has suburban rail entry structures in the surrounding green area.

The building spent decades as a reviled reminder of Soviet domination and the restrictions imposed under Soviet communism. When the Poles took control of their own destiny about 28 years ago, there was considerable pressure to dismantle the Palace as many felt it was a symbol of oppression. The parliament defeated a measure to demolish the building, despite significant public pressure. Today, the Palace seems to have been, at least reluctantly accepted. It is now impressively lighted at night.

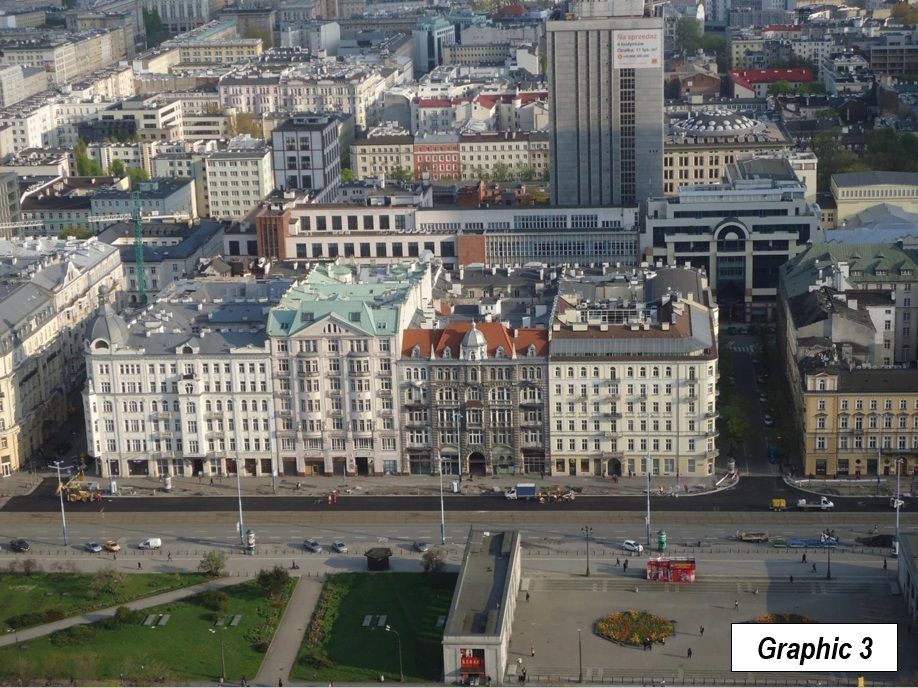

Since that time, the building has had a significant change in function. The building now houses offices, a museum, university facilities, the Polish Academy of Sciences, a fitness center and other functions. Even so, some people will still tell you that the best place to see Warsaw from is the Palace of Culture and Science, because it is the one place from which you cannot see the building. However, the view from the top is certainly worthwhile (Graphics 3-8).

A number of new, modern skyscrapers have been built, principally to the west. The buildings, however, are not closely packed, as would be expected in an American, Canadian, or Australian central business district. Graphic 9 shows the skyline, with the Palace of Culture and Science in the center and other large buildings around it. The distribution of Warsaw's post-Soviet commercial high rises is similar throughout both the central districts and the inner districts, widely spaced and reflecting a modern metropolitan area that has become much more automobile oriented.

The central district also includes the intersection of (Pope) Jana Pawla II and Solidarity (the trade union led by Poland's first post-Soviet president, Lech Walesa), boulevards named for two of the strongest forces responsible for separation from control by the Soviet Union and restoration of Polish independence (photograph at the top). Significantly, one of the corners of the intersection is occupied by a McDonald's, one of the most obvious symbols of the market economy that Poland has embraced.

The central district also includes the "old town," which like most of Warsaw was reduced to rubble by the bombing and street battles of World War II, including the premeditated destruction of the city by retreating German forces. It has been painstakingly rebuilt as it was before (Graphic 10).

Other Districts of Warsaw

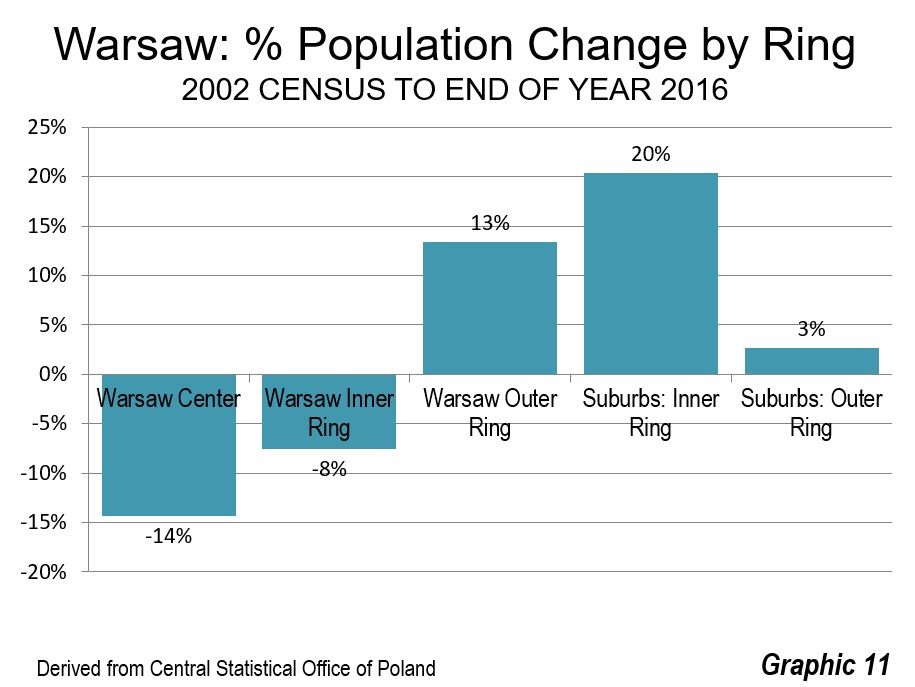

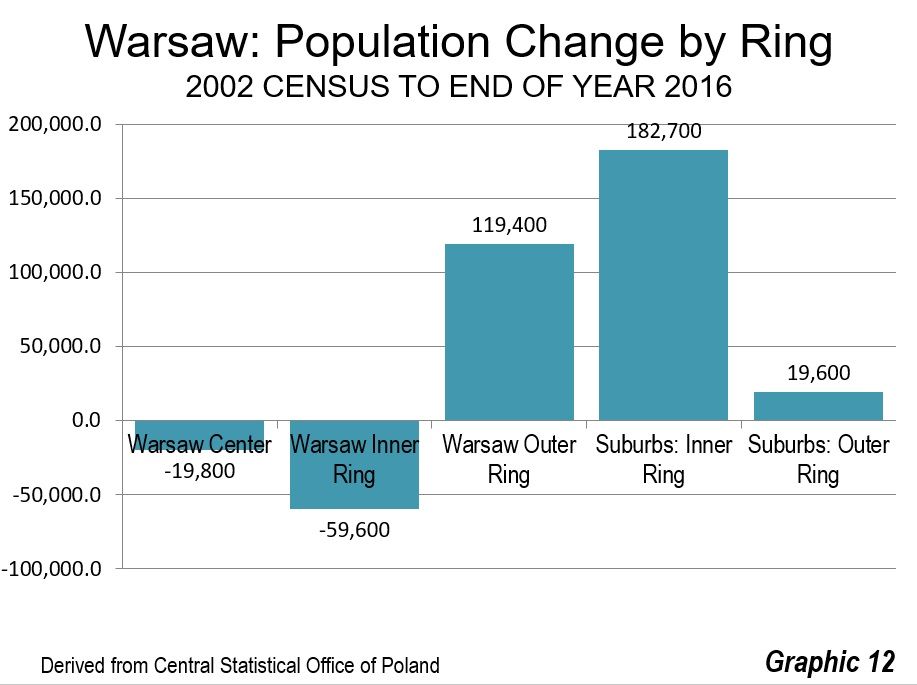

The inner ring of districts, each of which borders on Śródmieście, lost eight percent of its population between 2002 and 2016. These six districts include Mokotów, Ochota, Praga Północ, Praga Południe, Wola and Żoliborz.

The outer city districts gained 13 percent in population. Their nearly 120,000 gain more than offset the 60,000 loss in the inner ring districts and the 20,000 loss in the central district.

Suburbs and Exurbs

The inner suburban powiats captured most of the growth, growing 20 percent, and adding 182,000 residents. Growth in the outer nine counties was much less, at three percent and 20,000. Nearly 85 percent of the Warsaw area's population growth occurred in these suburban and exurban areas (Graphics 11 and 12).

The suburban and exurban residential areas are comparatively sparsely developed. Development is more contiguous in the inner ring of suburbs and much less dense exurbs of the outer ring (Graphics 13-16). Many suburban and exurban residential streets are far narrower and often without sidewalks and curbs. The suburban infrastructure generally appears to be of a lower standard than is found in the suburban areas of Australia, Canada and the United States, where larger individual developments have been required to install wide streets, sidewalks and usually sewers, as opposed to the generally smaller or even individually developed parcels that are more evident in suburban Warsaw.

Nevertheless, Warsaw, and Poland, are developing rapidly. Real gross domestic product per capita in the nation has increased by at least three times since 1990. The shopping centers of Warsaw look very much like others in the core of western Europe, and even similar to those in Canada and the United States. The nation is constructing a high-speed motorway system, which has among the highest posted speeds in the world, at 140 kilometers per hour (87 miles per hour), though a number of important segments remain to be built. After many difficult decades, Warsaw and Poland are truly a part of modern Europe.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Top Photograph: Street signs at the intersection of Jana Pawla II and Solidarity, named respectively for their roles in securing independence from the Soviet bloc (Pope John Paul II and the Solidarity Trade Union, led by eventual President Lech Walesa). By author.