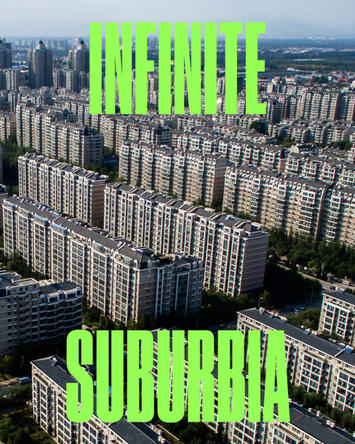

With 52 essays from 74 authors, Infinite Suburbia’s 732 pages comprehensively analyze the suburbs from the perspectives of architecture, design, landscape, planning, history, demographics, social justice, familial trends, policy, energy, mobility, health, environment, economics, and applied and future technologies. Organized by theme in an index that best resembles a spider’s web, the book is meant to be read in a nonlinear fashion, reminiscent of a choose-your-own-adventure novel. The editors of The Architect’s Newspaper (AN) spoke with the book’s editors, Alan M. Berger and Joel Kotkin, about the future of the suburbs.

Many of their analyses and provocations upend our notions of what the suburbs are and what they will become.

The Architect’s Newspaper: What is suburbia and how do you define it for this book?

Joel Kotkin and Alan Berger: Suburbia is generally a lower-density area outside the city core. In our approach, we look for such things as predominance of single-family housing, dependence on automobiles (particularly for non-work trips), age of housing stock, and distance from central core. This is about 80 percent of U.S. metro areas; some cities, like Phoenix and San Antonio, are predominately suburban even within their city boundaries. Within the book we have no fewer than five leading authors who define suburbia using different quantitative methods that are arguably more accurate than the U.S. Census at capturing the activities defining suburbia.

What are some of the myths that surround the architecture and design community’s perception of the suburbs?

Berger: Globally, the vast majority of people are moving to cities not to inhabit their centers, but to suburbanize their peripheries. I’m sure we can all agree that there are many suburban (and urban) models that are wasteful, unsustainable, and inequitable. However, despite having deep historical roots in conceiving suburban environments, the planning and design professions overwhelmingly vilify suburbia and seem disinterested in significantly improving it. Robert Bruegmann’s essay in the book reminds us that those who consider themselves the intellectual elite have a long history of anti-suburban crusades, and they have always been proven wrong. Our book, Infinite Suburbia, is built for an alternative discourse that can open paths to improvement and design agency, rather than condemning suburbia altogether. Our goal? To construct a balanced, alternative discourse to architecture and urban planning orthodoxy of “density fixes all,” and in doing so ask: “Can suburbia become a more sustainable model for rethinking the entire urban enterprise, as a vital fabric of “complete urbanization?”

Georgetown, Texas, United States. (Matthew Niederhauser and John Fitzgerald)

What were some of the most surprising or counterintuitive things you found about the suburbs when compiling these essays?

Berger: One of the consistent themes in the book, and what gets me most excited as a landscape scholar, is the virtue of low density and the ecological potential of the suburban landscape. Environmentally, suburbs will save cities from themselves. Sarah Jack Hinners’s research in the book really surprised me. It suggests that suburban ecosystems, in general, are more heterogeneous and dynamic over space and time than natural ecosystems. Suburbs, she says, are the loci of novelty and innovation from an ecological and evolutionary perspective because they are a relatively new type of landscape and their ecology is not fixed or static.

Kotkin: Two trends that may seem counterintuitive to urbanists have been the rapid pattern of diversification in suburbs, which now hold most of the nation’s immigrants and minorities, as well as the fact that suburbs are more egalitarian and less divided by class than core cities.

What did you learn from studying some of the suburbs that aren’t the classic idyllic American suburb as we might see in the media?

Berger: Not surprisingly, the American Housing Survey found that more than 64 percent of all occupied American homes are single-family structures. But in other countries, suburban contexts are anything but low density, such as along the peri-urban edges of Indian cities and those spread across China and Southeast Asia. Globally, not all suburbs look alike or follow the “post Anglo Saxon, North American model.” One fact remains, however, which is that in many parts of the world upward mobility is linked to suburban living.

How do you see suburbia changing in the next few decades?

Kotkin: Suburbs will change in many ways. First, they will continue to spread in those regions that have not employed strict growth controls. Denser development seems inevitable—such as The Domain [development] in north Austin—although [the suburbs] will remain largely surrounded by the single family and townhouses most people prefer. Although they already are, they will become more attractive to Millennials, who will demand fewer golf courses and conventional malls, and more hiking/biking trials and open, common landscapes. Suburbs will become more independent from the traditional city centers except for some amenities and central government services.

Berger: Autonomous driving will dramatically change how we live, particularly in suburbia, where the dominant form of mobility is cars. Once there is widespread adoption of electrified autonomous cars, dramatic sustainability dividends will flourish in the suburbs of the future. This may also take the economic strain off metro mass transit systems, which can focus on service improvements within the core areas rather than stretching outward. Shared autonomous vehicles will become the preferred form of mass transit in areas not serviced by traditional buses or rail.

What are the gentrification problems or other issues around the suburbanization of poverty?

Kotkin: Gentrification, often subsidized by governments, is driving poorer people from city cores to closer or—in some cases—more distant suburbs. These are usually places that are either far from workplaces or have a less desirable housing stock. Yet suburbanization of poverty needs to be put in context of the massive overall population advantage of suburbs; overall poverty rates in cities remain twice as high as those of suburbs, and the pattern has not changed much in the past decade.

What can designers or planners take from the book? Is there a role for traditional planning at this scale, when market forces are so strong?

Berger: Readers should convincingly take away the enormous opportunity ahead in designing more sustainable and equitable suburbs and the importance of suburban fabric to the entire urban enterprise. This is systemically evident from social, economic, environmental, and design perspectives. Of course, there is great agency awaiting designers and planners in the new suburbia. We created them in the first place, so we have a responsibility to evolve the forms and forces toward more sustainable futures.

This piece first appeared in The Architect's Newspaper.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Alan Berger is Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urban Design at Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he teaches courses open to the entire student body. He is founding director of P-REX lab, at MIT, a research lab focused on environmental problems caused by urbanization, including the design, remediation, and reuse of waste landscapes worldwide. He is also Co-Director of Norman B. Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism at MIT (LCAU).

Photo: Infinite Suburbia (Courtesy Princeton Architectural Press).