Ever since the economy began to bounce back, with unemployment at an all-time low, the familiar refrain from pundits has been that growth, particularly of the higher wage variety, would head to the tech-oriented elite cities along the coasts. Yet, today, despite the headlines about Amazon’s expansions in New York and Washington, D.C., the real story is the aggressive growth taking place on a changing stage, both in terms of geography and changing labor demands.

While tech is still among the fastest-growing job categories, up 29 percent since 2010, that’s not where the biggest shortfalls are now. Instead, jobs in food preparation, personal service, production and construction have the highest job-opening rates. In skilled blue-collar fields, there’s also the issue of a substantially older workforce—average age 45—than the general level.

An exclusive analysis of job trends for Chief Executive finds serious changes in the locale of economic growth. Although the Silicon Valley, and, to a lesser extent, its urban annex of San Francisco, continues to create higher-wage jobs, the momentum there has shifted primarily to lower-cost, less-heavily-regulated economies. Similarly, some of the “super-star cities,” such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Boston, are seeing only modest job growth, often at or below the national average.

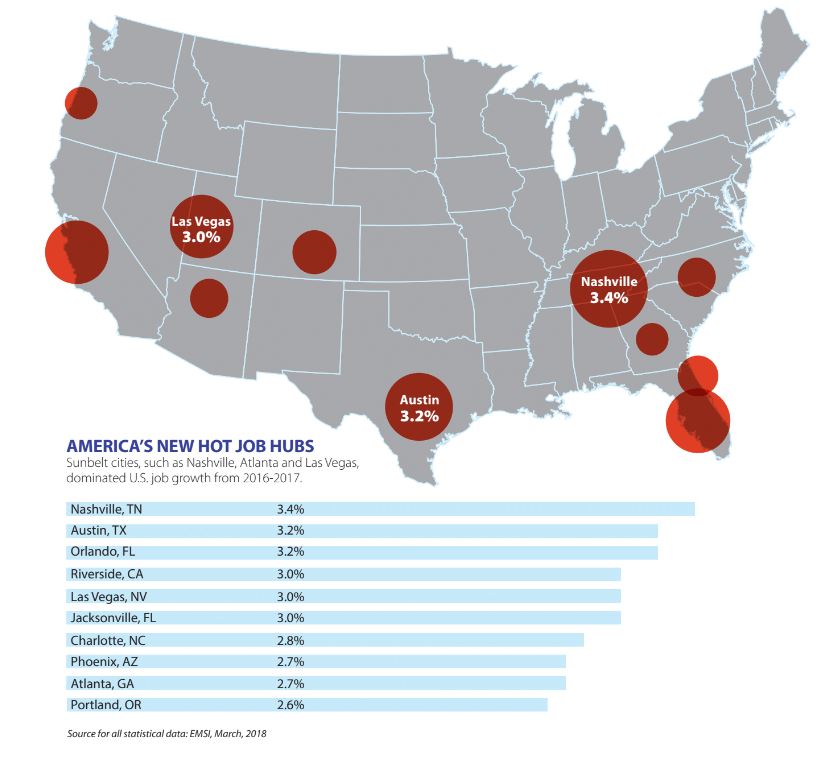

This can be seen most clearly by comparing job growth over the past seven years to growth over the last year. Metropolitan job growth from 2010 to 2017 looks like a hip, high-tech central casting. Top five metros include Austin, San Jose-Sunnyvale and San Francisco. Last year’s numbers, however, show a distinct trend towards Sun Belt cities, which accounted for all eight top-growing economies, including Nashville, Las Vegas, Jacksonville, Atlanta, Phoenix and Riverside-San Bernardino, an exurb east of Los Angeles.

The Leaking of High Tech

The Bay Area metro area job picture remains robust, growing well above the national average, yet no longer outperforming all comers in tech growth. San Jose-Sunnyvale ranked second, with 25 percent growth since 2010, but last year notched a respectable, but not overwhelming 15th, with San Francisco right behind at 16th. This reflects an ongoing shift of work in technology and business services to other markets.

We looked at the growth in computer and math-related jobs. Since 2010, the field, which includes 4.6 million workers, has been led by the Bay Area, which took two of the three fastest expansions of this critical sector. Last year, the San Jose area still ranked No. 2, but San Francisco, third since 2010, fell below 25 and slightly below the national average. The big gainers were first place Orlando, which added 7.3 percent to its employment in this field. Other rising Sun Belt upstarts include Las Vegas and Atlanta. Perhaps more surprising, places like Cleveland and Kansas City are growing up to twice the national average in this critical field and far more than self-described “tech hubs” Washington, Los Angeles, Boston and San Diego, all of which are producing new tech jobs at or below the national average.

Much of the geographic widening of tech work is made possible by the growth of high-tech business services, which tends to be more integrated with the economy and works often with non-high-tech sectors. The professional, scientific and technical services sector employs 1.7 million (36 percent) of computer and math workers, compared to just under 600,000 employed by the more celebrated software and Internet industries. More importantly, business services sectors generated 2.5 times more jobs for computer and mathematics workers than IT sector businesses since 2010.

The big issue behind this change may be costs, notably housing, as is widely admitted by tech industry leaders. Once wages are normalized, Bay Area workers’ relative salary plummets. Overall, the average salary in San Jose turns out to be less, in real terms, than places like Minneapolis, Washington D.C., Raleigh, Kansas City or Austin. Migration patterns from the Bay Area have changed radically over the past five years, with more people leaving than coming. Nearly half of millennials and more than half of all current residents say they are considering a move out.

The Business of Business Services

Employing more than 10 million workers, the biggest sector of high-wage jobs—paying $87,000 on average—comes from the business services sector. The dynamics here differ from what is traditionally considered high-tech in that this is a field that may not be as amenable to the urban phenomena of single, young people sharing small, overpriced apartments. Along with its 1.7 million IT workers, the professional and technical services sector employs more than 900,000 in management occupations.

We took a deep dive into management occupations—including top executives and managers of all types of employees—to get a sense of where these higher-wage jobs (paying $43 an hour, $4 above computer and math-related jobs) are heading. The picture shows considerable change. Taking the pulse since 2010 shows San Francisco and San Jose ranking first and third, respectively, in growth. But if we look at 2016-2017, the picture changes, with again the momentum weakening, particularly in San Francisco, which dropped from first in growth to a still-respectable 12th.

Who’s gaining? For the most part, it’s smaller, less-costly Sun Belt locations. Nashville and Las Vegas topped our list, but Phoenix, Atlanta, Salt Lake City and Jacksonville all made the top 10. Tech region standbys like Portland and Seattle are also increasingly outperforming other elite economies such as New York, Los Angeles and Boston by a wide margin.

These patterns are, if anything, more pronounced when we turn to financial management and general business operations services, as opposed to top management. Here it’s Orlando in fourth place since 2010, in first last year, with other Sun Belt cities, including Jacksonville, Raleigh, Las Vegas, Austin and Charlotte, in the top 10. Although it placed second, Silicon Valley retained an impressive five percent growth. San Francisco fell from fifth to 22nd, while most other superstars are actually falling below the national average.

The Blue-Collar Boom

Whether due, at least partially, to President Trump’s policies, blue-collar America faces its most enviable situation in years. Wages are rising for lower-income workers for the first time in decades. Manufacturing employment, which flattened in the last year of President Obama’s term, has picked up, adding 1.2 million jobs since 2010 and 400,000 since November 2016, enjoying its best growth since the mid-1990s. Even retail, a big employer of blue-collar workers, has expanded. Critically, incomes are up for the lower deciles of the labor force, including youth.

One sign of a blue-collar resurgence: the most serious labor shortages tend to be in fields that suffered heavily in the recession, such as personal service, transportation, production and construction. We zeroed in on production workers like welders, machinists, fabricators and plant managers. This part of the economy has been traditionally concentrated in the “Rust Belt” along the Great Lakes but is now spreading to other parts of the country. Grand Rapids, the leader in this category since 2010, still held a respectable 11th place. Detroit, the epicenter of industrial America, did better, securing a strong sixth-place finish, adding 2.3 percent to its already large manufacturing work force.

The biggest growth, however, is now largely in the Sun Belt, as evidenced by the presence of No. 1-ranked Nashville, which added 3.9 percent to its industrial workforce last year. Other Sun Belt cities in the top 10 include Las Vegas, Jacksonville, Orlando and San Antonio, all emerging industrial powers. In contrast, many Northeast and West Coast areas saw a loss of jobs for production workers in the last year, including Seattle, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Diego, Philadelphia, New York and Boston.

Rust Belt cities may benefit from these trends. Although many places are declining, some are seeing millennial migration, as well as the greatest growth in seniors. Since 2010, notes demographer Wendell Cox, Indianapolis, Des Moines, Kansas City and Columbus have all enjoyed higher rates of millennial population growth than New York, Chicago, Boston, San Jose, San Francisco or Los Angeles.

What the Future Portends

Given uncertainty around interest rates, the stock market, high-tech regulation and trade policy, it is not easy to predict the exact shape of the future. But the data seems to indicate a shift in the basic economic structure. Places like Silicon Valley, Seattle and Portland will continue to dominate in the high tech and some business service fields, but their growth rates appear to be slowing while new players emerge in both the less costly Sun Belt and a select Midwestern markets like Columbus, Kansas City and Cleveland.

At the same time, there are big increases in fields that pay wages that will allow a middle-class lifestyle in a less expensive areas but would leave a family near poverty levels in New York, Los Angeles or the Bay Area. After adjusting for cost-of-living using the C2ER index, places like Minneapolis, Kansas City, Detroit, Columbus, Raleigh and Cleveland move into the top 10 for median wage.

Ultimately, this pattern is being reflected in migration out of California and the Northeast towards the Sun Belt and a few Midwestern cities. These are also the areas that are showing the slowest decline in fertility, an issue that impacts both family migration and, in the long-term, the future of the job market.

The talent challenge may be shifting from luring workers from elite colleges toward developing local resources that emphasize the kind of specialized technical training needed locally. In many places, these programs—both in the high schools and community colleges—were scrapped in favor of a concentration on four-year degrees. But some areas are now taking steps to correct these deficiencies by linking local high schools and technical colleges using a career academy model. Close to 30 percent of all computer-oriented jobs, what could be called “new-collar” jobs, do not require a four-year degree, notes a recent Brookings study.

For companies, this may mean rethinking the best places to profitably access human capital. Impossibly expensive regions, such as the Bay Area, may remain magnets only for the highest-end professionals, or those with family money, but not for those who earn more modest wages. Some of the slowest labor force growth, notes economist Jed Kolko, is precisely in markets that on the surface might be most attractive to workers. In some sense, elite markets like Boulder, Silicon Valley, Boston and Boston now have the same problem some Rust Belt markets have had for years—even when there are jobs, it’s increasingly hard to attract people to the area to do them.

In contrast, lower cost areas like Greeley, Colorado, Provo, Boise, Austin, Orlando and Fayetteville, says Kolko, still have tight labor markets, but are still growing their labor forces. Yet, there’s also an important message for millennials and future generations: a college degree may not be as valuable as you have been told. The returns for college degrees have been in decline for at least a decade.

Perhaps the biggest opportunity, or challenge, may be in meeting growing needs for personal care, much of it to care for our rapidly aging population. This sector grew by 33 percent since 2010 and 5 percent in 2016-2017. Many workers in the field would benefit from basic training in healthcare and gerontology, as opposed to a four-year or master’s degree. The rapid movement of seniors to lower cost, mainly Sun Belt regions and smaller cities, including in the Intermountain West, could help create a natural market for such work.

Overall the new trends provide an enormous opportunity for many areas of the country that can both accommodate blue-collar and high-paid sectors, including big cities like Houston and Dallas, which are projected to lead the nation in new “mid-skilled jobs,” as well as many smaller communities. Their big challenge may lie in training workers in fields with the largest number of openings, such as construction and manufacturing.

This means there needs to be a strong emphasis on bringing young people into many tactile fields that pundits have claimed are “gone forever” but have now come back with a vengeance. In fact, despite all the information age banter, significant opportunities lie in the “middle-skill” jobs. In the last year, nearly 250,000 new jobs were created in the construction and extraction and installation and maintenance job categories, paying roughly $20 per hour. Another 600,000 new business operations specialists, managers and healthcare practitioners joined the economy at pay rates above $30 per hour.

Critically, regions also know that new arrivals are not likely to solve their shortages; the current rate of job-related moves is roughly half to one-third what it was as recently as the 1990s. This provides an excellent opportunity for regions that did not shine earlier in the decade but are making a marked comeback now. For scores of towns and cities, the looming labor shortage represents a golden opportunity—if they can take advantage of it.

This piece originally appeared on Chief Executive.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Mark Schill is a community and corporate strategy consultant with Praxis Strategy Group and Managing Editor of New Geography.

Photo Credit: Thomas Hawk, via Flickr, using CC License of Nashville.