High speed rail may be proposed as a climate change panacea here and elsewhere, but the results on the ground are less than promising. California Governor Gavin Newsom announced this week that the California high speed rail project would be scaled back to the route between Bakersfield and Merced, in the San Joaquin Valley (which the state has enough money for). In his “state of the state” speech the Governor said “…let’s be real. The project, as currently planned, would cost too much and take too long. There’s been too little oversight and not enough transparency.” Thus the expensive hope of linking the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Area with high speed rail, already substantively abandoned by the California High Speed Rail Authority, has finally been buried.

Britain’s proposed high-speed rail megaproject (HS2) may be joining California’s on the road to oblivion (Map: Figure 1). A senior government official told Channel 4’s Dispatches public affairs program (aired February 11): "The costs are spiraling so much we've been actively considering other scenarios, including scrapping the entire project" (Video: Summary of Dispatches program).

Such an action would not only cancel the two northern extensions (to Manchester and Leeds), but also the already under construction first leg to Birmingham (in the West Midlands). Parliament has not yet approved the extensions beyond Birmingham. Professor Stephan Glaister, former head of the Office of Rail and Road, told Dispatches “you just really have a white elephant if you only go to Birmingham.”

HS2 would be Britain’s second high speed rail line. The first high speed rail line was HS1, which operates from London's St. Pancras International Station to Paris and Brussels, through Channel Tunnel (Note). St. Pancras International is just over one-half mile from the planned terminus of HS2, Euston Station.

Cost Blowouts

Liam Halligan in The Spectator wrote HSR was slated to cost £33 billion ($44 billion), but the costs have escalated to at least £56 billion ($75 billion). Consultant Michael Byng told BBC Radio 4 that the segment to Birmingham is already at £56 billion ($75 billion), which would consume the entire projected budget, including the money needed for extensions to Manchester and Leeds. Daily Mail transport editor James Salmon reported that: “A string of reports have warned that Britain’s biggest ever infrastructure project will blow its £56 billion budget with experts estimating it could cost as much as £104 billion.” In Dispatches, Halligan questioned --- in view of the cost blowouts --- the validity of the cost benefit studies that justified the project.

Government officials, present and former have raised questions. According to The Independent, former transport minister John Spellar called HS2 an “ever-deepening bottomless pit”. A cabinet minister told The Spectator ‘The case for HS2 is and always was nonsense.” Former Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling expressed “grave doubts.” The Spectator suggested that it would be better to invest the money in improvements in the North, rather than a high speed line to London. This theme has been frequently echoed by others, as opposition has grown.

Doubling Down on Costs

HSR2 Chief Executive Mark Thurston told Dispatches that the entire project would be delivered for the budgeted £56 billion. After challenged by Halligan about the cost overrun reports, he doubled down, saying that “the budget for this scheme is £56 billion."

Slowing Trains, Running Less Frequently?

The pressure to deliver the project within the current budget has become so strong that the leadership is now considering slowing down the trains and operating them less frequently to save costs. This might be a way to preserve the present budget target, but camouflages the cost escalation. When the volume of corn flakes in the box is reduced, while the price remains the same, it is still cost escalation, though better hidden.

Walking Between High Speed Trains?

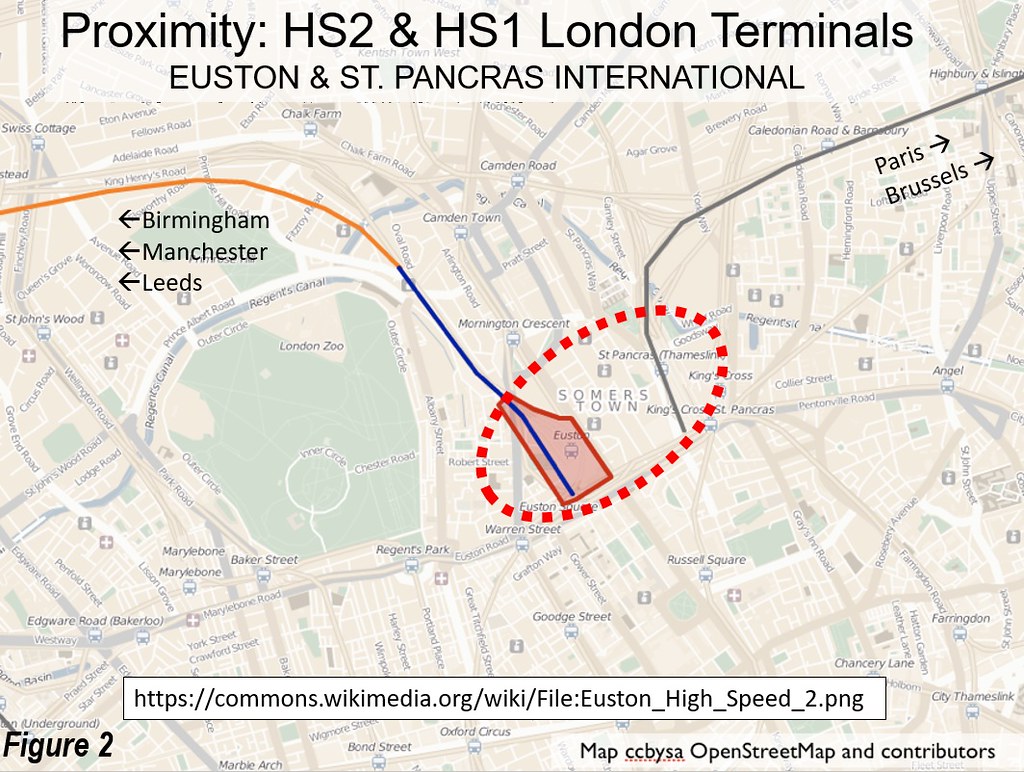

One of the cardinal rules of planning is to coordinate land use with transport. Yet, HS2 doesn’t even coordinate transport, with Britain’s two high speed rail lines terminating little more than one-half mile apart at Euston Road stations, without connecting (Euston Road Map, Figure 2). That this would be planned for London, among New York as one of the world’s two most important cities, is astounding.

Not surprisingly, critics complain that HS2 does not connect to HS1, “so doesn't provide the possibility of getting on a train in the North and getting off in Brussels or Paris.” Thus, a Manchester resident might make the connection, walking from Euston to St. Pancras International. Other options would be a trip to the next stop on the London Underground or a cab. It is an open question which would be fastest. None of these options is likely to be convenient, making some believe it would probably be better to fly. A government report says: “There is a strong case for improving the walking route between Euston and St Pancras,” but dismisses a through route. A walking route? What century are they planning for?

Opposition

There has long been opposition to HS2, much of it due to concern about cost escalation. Penny Gaines, chair of Stop HS2 told the Bucks Herald that “HS2 is a vastly expensive white elephant, with all the signs of busting its massive budget, it's time to cancel HS2…” adding that “Then the Department for Transport can get on with dealing with the rail and road issues that affect millions of people across the whole country rather than enabling a few people to get to a bit faster.”

Similarities to California

To Californians, all of this may sound like local news. Like HS2, the proposed California high speed rail project has experienced massive cost escalation. Like suggested for HS2, California has already rejiggered its plans to lower costs, by slowing trains in the largest urban areas and sharing tracks with non-high speed rail suburban trains. Like with the HS2, there was doubling down about costs until the reality could no longer be denied, and it was necessary to curtail system performance (See: California High Speed Rail: Updated Due Diligence Report).

The similarities are not surprising, and were identified as systemic problems in Megaprojects and Risks: An Anatomy of Ambition(2003), by Bent Flyvbjerg of Oxford University, Nils Bruzelius of and Werner Rothenberger of the University of Karlsruhe and former chairman of the World Conference on Transport Research. The authors examined decades of major transportation projects, including high speed rail, in Europe and North America and identified a general pattern of pervasive cost-escalation. Professor Flyvbjerg says: “Underestimation cannot be explained by error and is best explained by strategic misrepresentation, that is, lying” (see: “High Speed Rail: Toward Least Worst Projections”).

Time to Pull the Plug: The Telegraph

It seems likely that the “doubling down” will soon end and that the reality of the higher costs is waiting to dawn, as so often happens with these projects. The Daily Telegraph editorialized: “It’s time to pull the plug on this project. The money freed could go on desperately needed infrastructure projects, such as improving the roads. HS2 has only persevered because politicians and civil servants are drawn to any grand, large-scale project that burnishes their ego. But it is the public that picks up the tab and, just as with Brexit, the public is running out of patience.” (As it just has in California.)

Note: HS1 is used by Eurostar trains that operate from St. Pancras International to Paris and Brussels. In 2017 (before adding service to Amsterdam), ridership remained about 60 percent below the levels originally projected for 2006, with only modest growth since 2010.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. During that time, he authored the amendment that created the Proposition A 35% set aside that established the first local funding for the rail system. His involvement on the Commission is detailed in Transit in Los Angeles.

Photograph: St. Pancras Station (by author)