I just spent a few days in Stockton, California visiting old family friends. They’re a recently retired Lutheran pastor and his wife who relocated from Southern California and returned to their hometown. Being lifelong members of the church has many benefits, but making lots of money isn’t one of them. They run a lean operation and found a modest three bedroom two bath fixer upper for $195,000 and proceeded to do almost all the renovation work themselves. The house now looks great after decades of crud was stripped away, new fixtures were installed, and everything was given fresh paint on a tight DIY budget.

As much as I love their home it’s the neighborhood I really fell for. A walk around the block revealed a classic 1920s district of modest craftsman bungalows, Spanish revival cottages, tudors, and colonials mixed with more than a few large impressive homes all beautifully maintained and thoughtfully landscaped. Comparable properties in Los Angeles or San Francisco sell for millions. Stockton is a bargain basement Pasadena.

The palms that line the streets were originally used in the Panama Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco in 1915. The young trees were transported by barge to Stockton after the exhibition ended and have since grown to maturity. Like many similar neighborhoods of the era the land was developed around a streetcar line with grassy medians serving as trolley stops. Rail companies were established not to earn money from ticket sales, but to increase the value of property along the tracks. Railroads were first and foremost real estate development operations. Once the land was sold off at a hefty profit the streetcar system gradually declined. The trolleys were phased out entirely within a few decades as private cars and new highway construction displaced them.

There’s a Main Street (Pacific Avenue to the locals) near the university that’s promoted as Miracle Mile. You can get ice cream, buy paint, have a pleasant meal, shop for clothing or furniture, get a picture framed, visit the pharmacy, and so on. Stockton is a third tier provincial city so there’s a limit to the amount of excitement on offer. It ain’t San Francisco. Then again, this stretch of town actually functions in a reasonable way that I found charming. It doesn’t need to be San Francisco to provide 90% of what I might want on a daily basis. And this commercial strip is completely accessible on foot or by bicycle from surrounding homes. I’m always on the look out for a possible Plan B location and this town has its charms at a price I could manage. And I don’t need an airline to get there.

But Stockton is a good news/bad news town. The little streetcar suburb just on the edge of downtown that I find so appealing is sandwiched between two very different urban conditions. What exists on either side of my preferred neighborhood is what makes me scratch my head about the town. If I had to leave San Francisco for some reason could I really live in Stockton and be happy?

An old hotel caught my eye. As I approached it I imagined I could pop in and have lunch and people watch. Nope. The place appears to have some marginal occupancy on the upper floors, but each of the shop doors I tried at street level was locked and the windows were covered. A restaurant did appear to exist, but it was closed. And there wasn’t much in the way of people to watch.

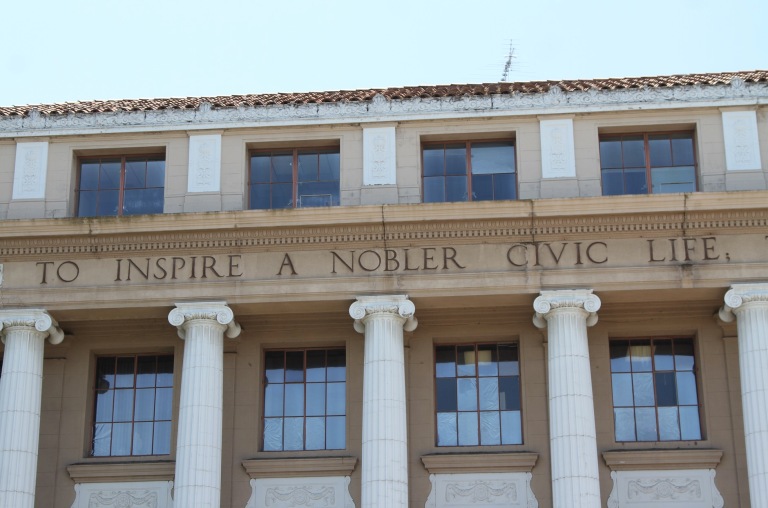

These photos from downtown weren’t cherry picked. This is what a majority of the properties are like. There just isn’t enough market demand to fill the available space. Downtown Stockton is basically a smaller and radically less expensive version of many of San Francisco’s best neighborhoods. But what’s the draw of great architectural bones if there’s effectively no flesh left? Is this a great opportunity to buy at the bottom of a long slow cycle ripe for an urban renaissance? Or is this a permanent condition? I can’t tell. And I might not live long enough to find out.

Now, on the other side of the 1920s neighborhood that my friends have settled into (the other half of the Stockton sandwich as it were) is a 1950s era suburban area. The homes are sweet. They’re priced about the same as what’s on offer in the older part of town. While these homes on cul-de-sacs have a Stepford Wives connotation for me they’re pleasant and well maintained. There are worse places to live.

Except… Pacific Avenue morphs from a walkable mom and pop Main Street into a much wider highway lined with drive-thru chains, shopping malls, and big box stores. This is what most of America looks like. And it simply doesn’t appeal to me. I don’t have to go to Stockton to experience this kind of landscape. It’s absolutely everywhere.

Just so you understand my perspective, this isn’t merely an aesthetic judgement. Here’s what’s immediately adjacent to the tidy 1950s homes. The aging commercial corridor is beginning to lose its shine. The buildings are past their useful life and it’s uncertain whether they’ll be bulldozed to make room for brand new drive-thru burger joints and fresh gas stations, or if market demand is already saturated for such things in the area. I’ve had this conversation so often in so many towns that I’m not sure it’s worth the bother of bringing it up again.

It’s possible to point to any number of retail plazas such as the Weberstown Mall and state with confidence that everything is great. And that might be true. For the moment. But everything has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Could people in the 1950s foresee the complete abandonment of downtown Stockton as new homes and shops sprung up in the alfalfa fields on the edge of town? It happened slowly. Then all at once.

The mall was built in 1966 and was anchored by Sears, JC Penny, Dillard’s, Macy’s and other such mid century retail giants. They were the middle brow suppliers to a stable fair-to-middling population that turned its back on anything old or historic. Everyone wanted ample free parking and air conditioning instead. These shopping centers didn’t add to Stockton’s older urban fabric. They replaced it. Now malls and big box stores are being replaced by the new new things just as the middle class they serve is rapidly shrinking.

How much longer do you think physical bank branches have before they’re raptured into the electronic ether? Paper money and checkbooks are going the way of land line telephones and Betamax. Could these places be repurposed and made relevant for the future? Absolutely. But then so could all those vacant buildings downtown… The difference between “could” and “will” is tricky. And how long might that take?

Will a new Applebee’s or Chevys replace the dead Red Robin? Maybe. Maybe not. There are plenty of these chains already lining the eight lane arterials in every direction as it is. And more than a few are also vacant. Is the strip mall and restaurant pod glass half full or half empty? I think that’s the wrong question. I want to know how many glasses are out there and who wants what’s in them. I drove for miles and the highway was a continuous ribbon of nearly identical establishments that were built decade after decade with the same rubber stamp.

So back to my favorite neighborhood. Could I live in the equivalent of the tomato slice and the mayonnaise in this big Stockton sandwich? Could I venture downtown once in a blue moon when I needed to visit the Department of Motor Vehicles? Would I mind driving out to the big box stores to buy toilet paper in bulk a few times a year? There’s a part of me that really wants a charming duplex on a tree lined street. And the price is right. I think it boils down to people. Could I find my tribe in Stockton? Are there enough funky individuals around to bond with and build a life around? I ask myself this a lot wherever I go.

This piece originally appeared on Granola Shotgun.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He's a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.