In a recent paper, David King of Arizona State University, Michael Smart of Rutgers University and Michael Manville of UCLA cited the legendary urbanist Mel Weber on the importance of facilitating sufficient mobility for low-income citizens: “Our central mission is to redress the social inequities thrown up by widespread auto use, and our central task is to invent ways of extending the benefits of auto-like transportation to those who are presently carless.”

This article considers research on the relationship between cars and poverty among low income households and uses examples from the San Francisco and Los Angeles metropolitan areas (which have the fourth and sixth largest count of transit commuters, respectively, in the nation).

Few Living “Near Transit” Use It

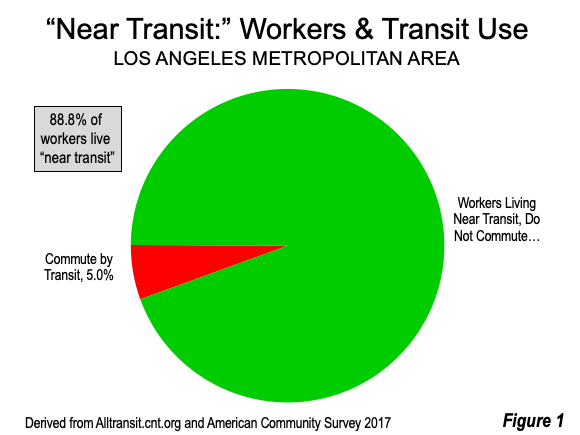

Weber’s advice may seem surprising to the general public, which might imagine that transit provides sufficient mobility to low-income citizens. Transportation planning agencies report the percentage of households living “near transit” as an indicator of transit effectiveness, using measures such as a half mile from a transit stop.

For example, Alltransit.cnt.org, ranks the Los Angeles metropolitan transit system as 6th best in the United States, out of 186. Alltransit.cnt.org indicates that 88.8% workers live “near transit” in Los Angeles. Yet, only 5.0% of Los Angeles commuters use transit. This speaks volumes as to the value of being “near transit” (Figure 1). Barely one in 18 commuters living “near transit” considers transit to be good enough to use instead of cars. Indeed, now nearly 97% of Los Angeles commuters have vehicles available, while the share of workers having no auto access dropped by nearly 18% from 2010 to 2018.

Commuting from Low-Income Neighborhoods

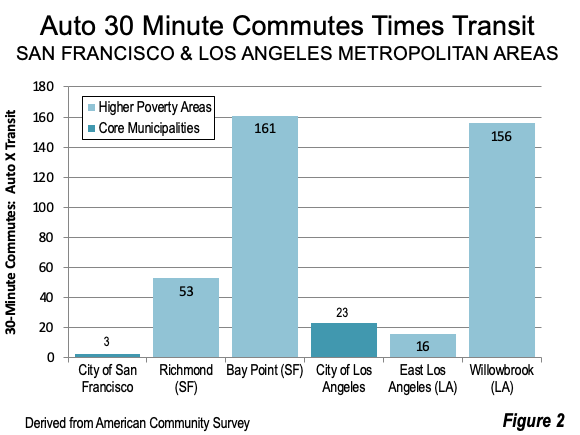

The city of San Francisco has the most intensive transit service in California. Yet, three times as many residents with commutes less than 30 minutes choose to travel by car rather than transit. In the city of Los Angeles, much of it built after 1950, when cars took over the heavy lifting of travel, and has a far smaller downtown area. In the City of Angeles residents are 23 times (2,300%) as likely to commute up to 30 minutes by car as by transit.

Even in higher-poverty communities, residents find cars more practical than transit for commuting. East Los Angeles, with frequent light rail service to nearby downtown Los Angeles, residents are 16 times as likely to commute by car as by transit. As distances from downtown get longer, cars become even more practical. For example, in San Francisco’s Bay Point, with its own BART station and frequent service on the Pittsburg line, residents are 161 times as likely to commute by car as by transit. In Los Angeles, Willowbrook, with a light rail station serving both the Green and Blue light rail lines with frequent service, residents are 156 times as likely to commute by car as by transit (Figure 2).

The reality is that “nearness” to transit does not mean that low-income residents have anything resembling automobile mobility. It seems universal auto access in these communities, would lead to less unemployment, less poverty and higher standards of living. This would benefit both lower-income households in particular and the metropolitan economy in general.

Shortest Distance Between a Poor Person and a Job is by Car

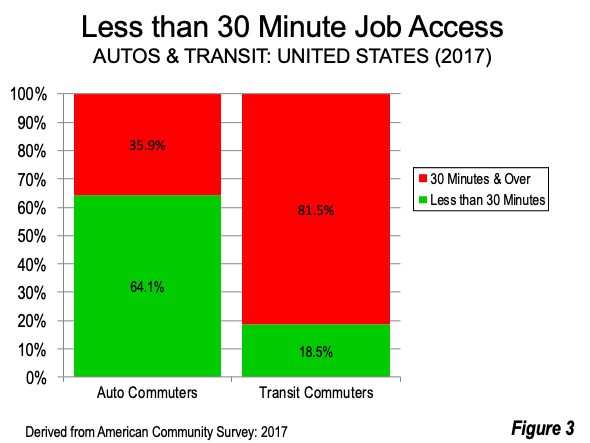

The fundamental difficulty is that transit is a corridor (one street) service, while cars access entire areas (for example all jobs within 10-15 miles). Riders can access two or more streets with transfers, but there is little time for transfers within the 30 minute travel time that most automobile commuters experience (Figure 3). Margy Waller of the Progressive Policy Institute (1999) stated the reality: “In most cases, the shortest distance between a poor person and a job is along a line driven in a car.” Indeed for many low-income residents, being “near transit” is near meaningless, because the accessible job opportunities are so limited.

A 2014 study (Driving to Opportunity), led by Rolf Pendall at the Urban Institute associated automobiles with a “positive role” of automobiles in outcomes” for households receiving low-income housing vouchers. Pendall wrote in CityLab, "The importance of automobiles arises not due to the inherent superiority of driving, but because public transit systems in most metropolitan areas are slow, inconvenient, and lack sufficient metropolitan-wide coverage to rival the automobile.”

Lack of Cars Associated with Greater Poverty

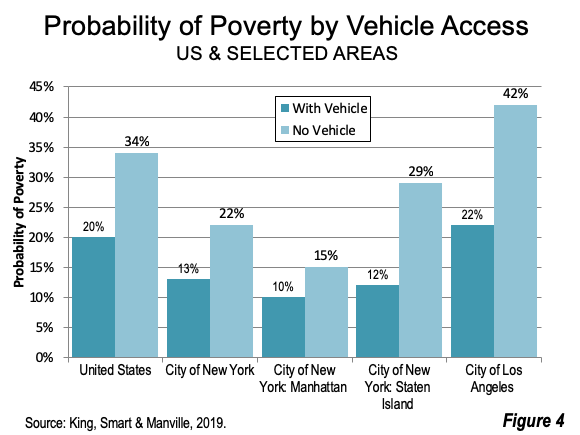

In perhaps the most important recent research, King, Smart and Manville found that US households without access to vehicles have a 70% greater chance of being in poverty than those who have access to vehicles. They also found that, generally, not only do households without vehicles have lower incomes, but their incomes rise at a lower rate (Figure 4).

Results were better in New York’s Manhattan, with only a 50% greater chance of poverty for those without cars. However, jobs-rich Manhattan has three times as many jobs as resident workers, so better results are to be expected (it is not just about density). The jobs to worker ratio of Manhattan cannot be replicated in a genuine labor market (a metropolitan area), which by definition has just one job per resident worker.

Toward a People Oriented Perspective

These kinds of analyses have generally been largely ignored by policy makers, or even criticized.

For example, Angie Schmitt of Streetsblog USA criticized Pendall for making “the case that ‘access to cars’ should be a higher priority for policy makers in the fight against poverty.” She suggested that Pendall and Washington Post reporter Emily Badger (who wrote positively about the conclusions) had implied that “transit advocates are somehow working at cross-purposes with the needs of low-income people”.

Genuine poverty reduction measures are demonstrated by results — intentions and rhetoric are irrelevant. Low-income households should not be held back from opportunity and better lives by the structural inability of conventional transit to provide sufficient mobility. Their need for mobility is immediate, in contrast to long term transportation plans that rarely anticipate significant employment access improvements.

King, Stanley and Manville make a compelling case: “One objection to the goal of universal auto access is that driving carries serious externalities, so planning and social policy should promote less rather than more of it. By that logic, however, society should also not help lower-income households access electricity or heating fuel. Burning fossil fuels to heat and power households generates greenhouse gas emissions that rival or exceed those from cars. Yet we do not deny heat and power to the poor in the name of sustainability.”

Technology: The Ultimate Solution?

Obviously the ultimate solution is door-to-door access, which could become practical with the emergence of automated cars. This could provide transit with unparalleled opportunities for matching low-income workers with far more jobs. If some of the more optimistic cost projections are realized, many more may be able to pay for their own cars, and no longer need subsidies at all.

Photograph: Vintage Trolley on Market Street, San Francisco (by author)

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed by Mayor Tom Bradley to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. Speaker of the House of Representatives appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Corrected Figure 3, updated May 2022.