If Biden’s American Family Plan becomes law as he proposed it, my grand-niece Harri will finally have a “modest yet adequate” standard of living based on a new commitment from the federal government to provide social wages.

Harri is a 30-year-old single mother of two, one 3-year-old and one in school. As an assistant manager at Walmart, she makes about $47,000 a year, but about $8,000 of that goes for day care for her preschooler. She recently started getting $550 a month in a Child Tax Credit (CTC), but that’s just a temporary boost for the next year that was part of the Democrats’ March stimulus package. If the Family Plan becomes law, she’ll get that CTC money for another five years and her preschooler will get free pre-K public education, freeing Harri from paying for day care.

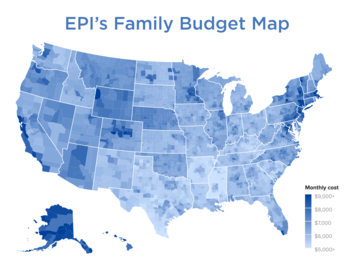

Add it all up, and Harri’s income will be topped up by $6,600 and she’ll be saving $8,000 a year on day-care costs. She’ll go from having $47,000 a year in reported income to having $53,600, but with the absence of day-care costs, her real spending income will be enhanced by $14,600, a 37% increase. Where she lives, in central Pennsylvania, the Economic Policy Institute figures that with no child care costs, she would need about $49,000 to have a modest yet adequate standard of living. Harri will have a little more than that. $53,600 will not provide her with a life of luxury, but the magnitude of that change should be transformative for Harri and her children.

Harri will get more than parents with fewer kids or fewer pre-schoolers, but she’ll get less than parents with more kids or more than one preschooler. The point is that the combination of the CTC and public pre-K (plus an additional program where parents of one- and two-year-olds will pay no more than 7% of their income for day care) will make a dramatic difference in most parents’ and children’s lives. It is often said that the CTC by itself will cut child poverty in half. But the whole combination will do much more than that for many more families, including those who are not poor but struggle to get by.

Beyond its variety of impacts on different American families, Biden’s Family Plan is a breakthrough commitment to the concept of social wages, a concept that has even wider application. Along with other Biden initiatives, there appears to be a firm Democratic recognition that most workers are paid too little in market wages to get by and that the government has a responsibility to change that.

Social wages are different from the commonly (and loosely) used phrase “social safety net.” Safety-net programs, like unemployment compensation and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, are for people who have fallen on hard times for one reason or another. Like a net, they keep people from falling farther by providing temporary income until they can get back on their feet.

Social wages, on the other hand, are more permanent, less means-tested, and available for much larger groups of people. They either subsidize essential workers by increasing their pay or reduce costs of common goods and services. Among Biden’s various plans, for example, are wage subsidies for home care and day care workers who now average $23,000 and $22,000 a year respectively. Obamacare subsidies and the Earned Income Tax Credit do this for a broader group of low-wage workers. Many cities with strong labor movements, like New York, have long had reduced transit fares and rent control to keep costs affordable for low- and moderate-wage workers, though better-paid workers benefit as well. In the postwar years, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union established cooperative housing and even a non-profit bank to reduce their members’ and other workers’ cost of living.

Read the rest of this piece at Working-Class Perspectives.

Jack Metzgar is a retired Professor of Humanities from Roosevelt University in Chicago, where he is a core member of the Chicago Center for Working-Class Studies. His research interests include labor politics, working-class voting patterns, working-class culture, and popular and political discourse about class. He is a former President of the Working-Class Studies Association.