I’m old enough now to have grandnieces and nephews, and almost all of them have lower living standards and worse working conditions than their parents. And their parents had it worse than their grandparents. The one exception is Carrie, who recently graduated from college and works as a medical technologist, making one of the best salaries in three generations of our extended family. She grew up in poverty, the child of a teenage mother who was a ward and prisoner of the welfare system for the first decade of her motherhood. Carrie and her mother worked hard to climb out of poverty, and Carrie’s success is heartening in a family that has seen so little of it.

My extended family reflects patterns of upward mobility in the US today. Only a handful of people born in the bottom half of the income hierarchy move up, but they are often seen as evidence of the continuing promise of the American Dream. Most people born since 1980, however, are living diminished lives compared to their parents.

This situation shows why absolute upward mobility is more important than relative upward mobility. Understanding the difference makes clear why we should focus on the conditions of people’s lives, not just their opportunities to move up a social class ladder.

Relative upward mobility is when people born into a lower income quintile rise to a higher quintile. It has stayed roughly the same for more than 50 years. Most people born into the top two quintiles at any point since 1970 have stayed there as adults, while fewer than 1 of 10 born into the bottom quintile, like Carrie, make it to the top 20%. This means we’re getting no closer to equal opportunity than we were a half century ago.

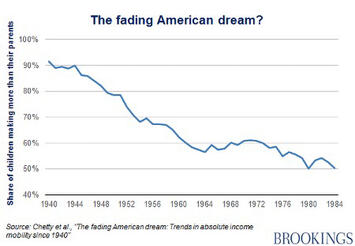

Absolute upward mobility measures whether people earn more than their parents did. And it has been declining for more than 50 years. Over 90% of children born in the 1940s, for example, earned more as adults than their parents did, regardless of whether they moved up any quintiles. As real wages and family incomes increased across the board, almost everybody lived better than their parents. But only about half of those born in 1980 have family incomes greater than their parents, and it’s even worse for those born since then.

Carrie illustrates both kinds of upward mobility, but it is what her income provides, not the quintile it puts her in, that matters the most, for her and for our society. Absolute mobility measures changes for the population at large, not just where individuals land relative to where they begin. Rather than referencing heartening individual stories of struggle and success, absolute mobility is a dry statistic that tries to capture the macro-level whole. Is a rising tide lifting or sinking most boats? As the graph above shows, most of us have been sinking for quite a while, and there is nothing heartening about that.

Read the rest of this piece at Working-Class Perspectives.

Jack Metzgar is a retired Professor of Humanities from Roosevelt University in Chicago, where he is a core member of the Chicago Center for Working-Class Studies. His research interests include labor politics, working-class voting patterns, working-class culture, and popular and political discourse about class. He is a former President of the Working-Class Studies Association.

Chart: The Fading American Dream, source Raj Chetty.

Purchasing Power

Perhaps I did not read carefully enough, but over those last 50+ years the cost of consumer goods and most other things has fallen, so that today's young adults possibly have as much purchasing power as their parents/grandparents? The one exception is housing--today's adults are definitely house-poor relative to prior generations.

So maybe the mobility analysis ought to factor that in, unless it already does and I am just missing it. But as a 60-something I look at my own adult children and they easily have the same, and in some ways, higher standard of living than I did or their grandparents did at the same age (leaving housing out of the equation).

Of course, the fact that there are more consumer goods available to purchase today than 50+ years ago, and that they are affordable even by lower income quintiles, does not necessarily mean that the "quality of life" of young adults today is better than it was for their ancestors, but that is an essentially subjective judgment, and in no way a fact, which is why I placed it in quotes.