Perhaps because I’m from the Midwest, I’m always fascinated by the factors that drive economic growth and decline, particularly at the metro level. I often hear that when a metro area is experiencing a boom, pundits say that declining metros ought to replicate the actions and policies of a booming one. My instinct is to say it’s not always that simple; booming metros often have an underlying cultural or economic foundation that aligns with the latest phase of economic growth, while declining metros are often burdened with the cultural and economic legacy and infrastructure of a previous boom phase. This creates a distortion of economic perspective in both booming and declining metros. Booming metros believe they’ve worked hard to attain a certain level, yet it’s quite possible things simply aligned in their favor. Declining metros are stuck trying to emulate the strategies of booming metros and not getting the same results, largely because they’re neglecting to address foundational issues that keep growth at arm’s length. Booming and declining metros could both benefit from reality checks that come with greater metro introspection.

That line of thinking took another level after I attended a conference last month in Houston, which I wrote about here. It led me to consider larger issues related to metro economic growth. To what extent does a metro area’s workforce composition influence its ultimate economic direction? Do social and cultural changes determine metro winners and losers? Do changes in lifestyle or technology create metro winners and losers? Can lifestyle or technology sustain the winners, or do they create another round of winners and losers?

I think a lot of people fail to remember that economics is a social science, meaning that it’s subject to the social (and cultural) biases we as humans bring to the table. When metro economies develop, they’re not just rational systems intended to produce a certain outcome or result. They are often related to specific and inherent strengths that metros can exploit, or weaknesses that they can cover. Over time metro economies become a social/cultural construct that bears all of the markings of the people who created it. One way to look at the makeup of a metro economy is to look at workforce composition. The workforce is a reflection, a snapshot, of the social/cultural makeup of the metro economy.

That led me to start a new project that examines workforce composition for U.S. metro areas, to see if there’s anything to be learned about how metro economies are structured, how they’ve evolved in recent years and where they could be going. I wanted to know what workforce composition could tell us about how metro economies are functioning, possibly even identifying metro economic strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

I looked at the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics website, where on the On The Map page one can download information on workforce composition by NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) Code by geography. For the uninitiated, the NAICS system is an economic classification system that categories economic sectors within twenty broad categories. It’s been in use since 1997, when it replaced the SIC (Standard Industry Classification) system and more closely linked American economic classification with Canadian and Mexican classifications, creating a North American standard. I downloaded the data for the 35 U.S. metro areas that had more than 2 million residents in 2020, with 2019 being the most recent data. The data tells us quite a bit where metros stand, and we can infer how they got there – and where they may be going.

Let me explain the metro economy assumptions I went into this exercise with, so I can lay the foundation for the exploration. First, I think it’s been widely accepted by economists and urbanists that the drivers of metro economies for the last 40 years or so has been the growth of the highly educated, professional, knowledge-oriented segment of the workforce that’s gained the title of the “creative class” thanks to Richard Florida and his work. Second, I’d add that services of all types contribute much more to the economy than they did 40 years ago, whether they are personal services, food and hospitality or accommodations.

Read the rest of this piece at Corner Side Yard Blog

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine's online platform. Pete's writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years' experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

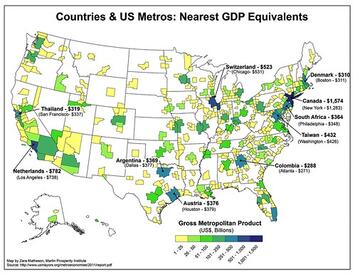

Image: The economic power of many U.S. metros is equivalent to other nations around the globe. Source: smartcitiesdive.com.