by Richard Reep

Like a heroin addict going cold turkey, Florida appears poised to get off the growth drug this coming fall. If massive overbuilding, unemployment, depopulation, and a tourist-chasing oil slick weren’t enough, Florida’s voters are in the mood to vote yes on a referendum called Amendment 4, which would make every future change to the state’s comprehensive plan subject to voter approval, rather than be reviewed through a representative public process. The referendum capitalizes on short-term voter outrage over everything. But in the long term, Florida will likely languish in the twilight of missed opportunities as businesses relocate elsewhere to avoid risky, lengthy public campaigns to build their presence in this state.

Between 1845 and 2009 Florida became the fourth most populous state in the nation. Because of its immense desirability, land developers have become legitimate partners in Florida politics, and have dictated much of its growth management legislation in the modern era. A byproduct of this process, however, has been increasing resentment among those who came for affordability and a low-density lifestyle, as cow pastures and orange groves got mowed down for subdivisions and malls.

Traffic and congestion, which many migrants thought they would magically leave behind up north, came with them. Since before the 1980s, the popular press has published article after article about citizens who came for the good life, only to see nature replaced by concrete. Many who came seemed genuinely puzzled about this transformation, as if they expected that human activity would have no noticeable impact.

Laissez-faire politicians kept the debate from becoming a serious topic, for the land seemed limitless, and the state’s leadership preferred not to dignify this seeming selfishness with a response. The response to those who wanted to lock the door after they had arrived was silence. This time around, emotions have acquired a larger momentum in the form of Amendment 4. Those who support it, such as writer Dori Sutter of the Orlando Sentinel, claim that Florida is overbuilt and has the ability “to create jobs and revenue and to accommodate population growth of more than 80 million people.”. In other words, Sutter’s point is that the current growth management model will accommodate an additional 60 million people over Florida’s current population – if the future immigrants are content to use this model exactly as it is drawn today, with no exceptions.

Right now is an opportune moment for Florida to clean up its act. Voters might be more likely to approve housekeeping moves to repurpose abandoned properties and improve the aesthetics of the built environment. This kind of activity, however, depends upon businesses moving in, and most business owners handle enough risk without adding a political campaign to their plates. If Florida resembled, say, Europe in its sense of place, then Amendment 4 would be a stroke of genius.

As it is, Amendment 4 would be the mother of all reset buttons, and voters who push this button in November would freeze the state’s built environment at its worst, not its best. This pause would bifurcate the state’s economic pathway away from the previous course of growth for growth’s sake, and set the stage to diversify the economy and allow Floridians to discover their own destiny through direct democracy. As such, it represents a grand experiment in process, replicating New England-style town hall debates over the nature and the future of the community.

In the long term, however, this new pathway is far from guaranteed to make for a better process. For one thing, rational facts and figures hold little stock compared to emotional appeals during an election campaign, and every change to the built environment will face as many detractors as it will supporters. Decision-making will likely result in as many bad calls as the process does now.

Property development is a complex, high-stakes game involving many public and private players. Emotional appeals to voters will tend to reduce this process to matters of style and aesthetic appeal, glossing over technical issues. And, when these matters are put to broad votes, safe pathways will likely win over innovative pathways and inventive ideas, further miring the state in the past. This is why property development has historically been left to the government to handle, with representative democracy in the form of public development commissions, and limited participation by way of public hearings.

Those who want to put every 7-11 and office building to the vote recognize the change that it would make to Florida's growth management process, as well as to the state itself. This season of voter outrage seems to be the moment to punish Florida’s favorite villain, the evil developer, as well. Florida seems to have hit an impasse where the current process has yielded an unfavorable product. While citizen input has largely gotten the state where it is today, the results are widely viewed as unsatisfactory.

Currently, no compelling argument has been put forth against Amendment 4. Homebuilders and developers protest that the process is fine as it stands. Citizen boards, administrative review boards, and public hearing stakeholders are made up of Floridians who approve a Comprehensive Plan every five years, and then review changes to the Comprehensive Plan when landowners request these changes to suit their needs. Sophisticated and complex, this process already involves environmental protection, detailed technical work, and deep pockets.

Those put in charge of growth management find it hard to say "no" when the state’s property tax coffers, (along with sales taxes) fund much of the public realm. Since growth — development — funds much of the state government's activities, growth management acts as a financial conduit, one hardly likely to be restricted by those in charge of it. Saying “no” is just not part of the process.

If the process represents a public conversation about how a city or a region should grow, disgust with the conversation has risen to new levels. Floridians are in the mood for grand solutions: witness last October’s vote in Miami for Miami 21, a form-based zoning code that replaces the zoning process with a product, a Master Plan, of sorts, for the city. Miami 21 appears to be stopping the conversation by limiting future generations’ ability to influence the pathways on which the city may economically develop.

Amendment 4, rather than reforming the process, also tries for a grand solution. Public debate will be characterized by posturing and politicizing, hardly conducive to rational discussion of complex, technical issues. Where growth is already been well-managed, this might be acceptable, as these regions will organically fine-tune their infrastructure. Where growth has been poorly managed, however, lack of services, traffic congestion, and patchwork development patterns will punish residents and governments alike with declining property values and reduced quality of life.

The long-term consequences will inexorably reshape Florida’s future, and income from activities other than real estate development will have to be considered for the very first time in Florida’s history. Gaming – already looming large in Florida’s future – is one possibility. A state income tax is a distant possibility, although a state with a large, low-wage service population will likely be unsatisfied with this kind of shot in the arm.

Thomas Jefferson said, “The government you elect is the government you deserve,” and Florida’s government managed growth in a way that Floridians deserve. Today, with profound disgust at the result, voters appear poised to start over, this time without the government’s help. If growth is no longer Florida’s favorite drug, then with Amendment 4 the state will suffer through cold turkey as businesses relocate elsewhere. A diverse, robust economy may or may not result from this dramatic change. If it does, then Florida will truly get the state that it deserves, and emerge stronger from the depths to which it has sunk. If, however, this move cripples the state’s recovery, then politicians will have some hard work ahead to reestablish trust among voters, and adapt the state’s revenue system and growth management system to a new, no-growth public mentality.

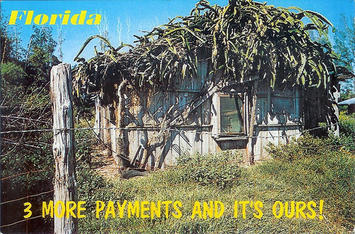

Flickr photo of a vintage Florida postcard by Mary-Lynn

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

Sadly that this will be the

Sadly that this will be the type of home you will get soon after everything you sacrifice and invested. There should be a revision on housing law.

Regards.

Reese Hopkins

"see me at http://www.digitekprinting.com/offset-printing-2"

Good Article, What Can You Do Though?

"I found the article to be somewhat disorganized. When I have to re-read sentences to discern their meaning, I am discouraged."

Disagree, it was well-written, without the academic heaviness that plagues so many urban blog posts, and I learned something about Florida. Appreciate Mr. Reep sharing his views.

Miami 21 is a complete disaster, so I wonder if there's any hope of fighting Amendment 4?

And is it just slow growth, or is Florida hoping to turn the whole state into Seaside or Celebration?

The story of Florida for the

The story of Florida for the past 30+ years has been that it has basically become the retirement pastures for people from New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, and Maryland. Basically the North. I grew up in TN and whenever we took our annual trip to the beach it always struck me as funny as to how many people with Brooklyn accents lived there.

The bottom line is that Florida has to much reliance on retirees. In order to have a catalyst for growth you need a diverse economy and Florida lacks anything close to that type of economy.

Too much wandering for me

I found the article to be somewhat disorganized. When I have to re-read sentences to discern their meaning, I am discouraged.

Bad for Florida - great for South Carolina

I've been aware of Florida's growth and policies now for over three decades. The building industry during this time represents a bouncing feast or famine profile.

Those in planning that believe that better development can be brought about by having the surrounding neighbors have decision making power over the developer as a better way to build cities are fools. We designed Creekside southeast of the Tampa area, a development of 1/2 acre lots with luxury housing that conformed to the ordinance. One of the requirements was that the rear lot lines abutting the surrounding neighbors be 200 foot wide at the rear lot line. This is typical of regulations designed to appease neighbors. When I visited the site after most of the development was built I looked at the neighbors homes which were old mobile homes!

Here are the facts - in all my years of planning I've never seen a neighbor saying - wow, this will be a great development in my back yard - I cant wait to close all that open space up with neighboring homes overlooking my private yard. Now give those people voting power, and see what happens!

The fact is that the average home sells every 6 years (not including this recent housing crash that skews the numbers lower) - so you are giving power over the development to a nearby resident who is not likely to live near the development past the completion of Phase One!

Do developers know best? Not necessarily, but they are concerned that the development is financially viable, the neighbors care less, but they should be as their property values will plummet if that adjacent developent fails.

Just some comments, but if Florida passes this it will be another reason to move up to South Carolina where land is lush, the Ocean is not too far away, and housing is affordable, as well as insuring the homes.

all good points Rick

I was thinking about the neighboring property to a house that I showed yesterday (I am a realtor). The house was built in 1978 on a large lot (acre and a half). A lot size not available to a new home buyer in that area anymore.

In 1978 it was a mostly rural area, outside of town. The house was built to take advantage of the view, in fact its the biggest feature of that house. A view mostly of a farm field and some woods. However the property in the view isn't the homeowners (it does have a big back yard), it belongs to the farmer that farms it. So when that field gets developed, and it will, its natural that homeowner isn't going to be happy about it. That pretty field will someday become the vinyl sided backsides of some new houses. So in the minds of most people, they will think the value of their home will decline, even if it doesn't.

The only surprise to me is that field didn't get developed already. So the view has already lasted for decades when it probably shouldn't have. So the fact that it didn't develop will only give existing homeowners the idea that it should NEVER be developed.

People have gotten in the mindset that they have a say on neighboring real estate when they really don't. Even though there are concerns like rainwater runoff, they shouldn't get veto power over other people's real estate and the right to make changes to it.

Will we need "right to develop" laws someday like the "right to farm" laws today that where necessary when neighbors of farmers tried to restrict farming activity?

It could make developing land an even more expensive job then it already is.

Making sure that the only remaining developers are the huge companies that people seem to hate the most. The harder it becomes the less small time developers there will be. So say goodbye to the local guy that knows the area far better then the big guy from somewhere else.