The financial collapse dominates the news, but its unregulated rise is not unrelated to the relative decline of manufacturing over the last quarter century, and the outsourcing of much of industrial production. One consequence of this de-industrialization and financialization of everything has been an astounding increase in inequality, a massive concentration of wealth at the very top and the squeezing of the middle classes.

Places that remained strong in manufacturing tend to have had and still have lower inequality than places more dependent on services, lowly to professional, and experienced a smaller change in inequality. This case has been argued by many, perhaps most eloquently by Zimmermann and Beal (2002) in Manufacturing Works, and by Scott (2003) The High Price of Free Trade.

Zimmermann argues the importance of industrial production for national and local prosperity. In Part 2, “Changing geography and what it means”, he treats the relocation of industry, and then follows with “Counties gaining momentum:, Counties losing momentum, and Big City Blues (Philadelphia and beyond)”. He notes the huge northeastern losses in industry coincided with increased inequality, e.g., New York, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Rochester and in large numbers of smaller metropolitan counties. In contrast decreased inequality in many places in the South, Mountain states and plains (e,g, ND, SD, WY, UT, NE) with rapid industrial growth.

Local economies dominated by manufacturing generally have had less inequality than ones dominated by services. Although this is particularly true in mostly northern states with a long history of labor unrest and successful unionization, even the more recent largely nonunionized industrialization in the South has reduced income inequality, although statewide levels remain a high, a hangover from their long pre-industrial and even feudal histories.

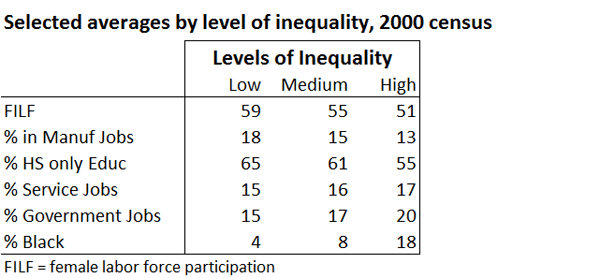

What distinguishes lower levels of inequality? In my work using Census data these areas generally experience female labor force participation, higher shares of manufacturing and a larger population with only a high school education (i.e., not overloaded with us professionals!), but lower shares of government and of services. Manufacturing is just one of many factors, but it is a powerful one.

It is instructive to look at some example areas of higher and of lower inequality in 2000 relative to the composition of their labor forces. The most unequal large areas/counties are New York (Manhattan) and Washington DC – by far, both with high levels of professional services and government, and low levels of industry. Also very unequal are many retirement and environmental service areas, with almost no manufacturing, such as St. Petersburg, Naples, Vero Beach and many other growing Florida cities, Jackson, Wyoming, and several ski dominated areas in Colorado and Utah.

In stark contrast, inequality is quite low in such strong manufacturing communities as Kansas City, Worcester, Appleton-Green Bay, Fond du Lac (and several other Wisconsin cities), Duluth, Grand Rapids, Davenport-Rock Island, Manchester, NH, Lancaster, PA and Tacoma, WA.

In sum, economic characteristic variation is real: egalitarian regions exhibit higher labor force participation, especially of women, and high levels of manufacturing – this is probably the most meaningful economic variable to account for lower inequality – and conversely higher inequality is associated with service and government job dependency. High shares of both managerial-professional occupations and service jobs, with lower shares of craft and manufacturing jobs are typically characteristic of elite metropolitan areas and helps account for their higher inequality.

Change in inequality 1970-2000

Since the 1970s most major metropolitan areas became less industrial and far more dominated by professional, finance, and other services, and by trade, and concomitantly, have become far more unequal. Prominent examples are Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit Minneapolis, Dallas, Houston, St. Louis, Atlanta, Rochester, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Birmingham, Baltimore and Boston – a roster of historic giants of industry.

There are probably only limited opportunities for these areas – particularly in California and the Northeast – to reindustrialize. Yet there may be more opportunities in dozens of smaller metropolitan areas, in all parts of the country, but especially in the historic Midwestern and Northeastern “urban-industrial” heartland, that have suffered varying degrees of deindustrialization. These places enjoy low costs and often retain concentrations of skilled labor. Places like Florence and Gadsden, AL; Pueblo CO; Peoria and Rock Island, IL; Evansville and Muncie, IN; Dubuque, IA; Shreveport, LA; Saginaw, Midland, Benton Harbor, Flint and Muskegon, MI; Binghamton, NY; Toledo, Akron, Dayton, and Canton OH; Tulsa, OK; and Charleston and Wheeling, WV all could benefit from a new emphasis on productive enterprise. But the question remains: does Congress or the next President possess the will to make this happen?

Richard Morrill is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Washington. His research interests include: political geography (voting behavior, redistricting, local governance), population/demography/settlement/migration, urban geography and planning, urban transportation (i.e., old fashioned generalist)