The New York subway is unlike any other transit system in the United States. This system extends for 230 miles (375 kilometers) with approximately 420 stations. It serves the four highly dense boroughs of the city (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx), each of which is 20 percent or more denser than any municipality large municipality in the United States or Canada. Much of the fifth borough, Staten Island, looks very much like suburban New Jersey and has no subway service, though has a more modest system, the Staten Island Railway.

Overall, the older Metros (Note 1), New York's subway, along with London's Underground and the Paris Metro dominated the world's urban rail systems for decades. Until the recent emergence of Chinese urban areas (Beijing and Shanghai), London had the longest extent of track in the world, followed by New York.

As one of the original Metros in the world, it might be thought that the New York City Subway's best days are over. That would be a mistake. It is true that ridership reached a peak in the late 1940s and dropped by more than half between the late 1970s and the early 1990s. However, since that time ridership has more than doubled, according to American Public Transportation Association data. And it is not inconceivable that new records may be set in the years to come.

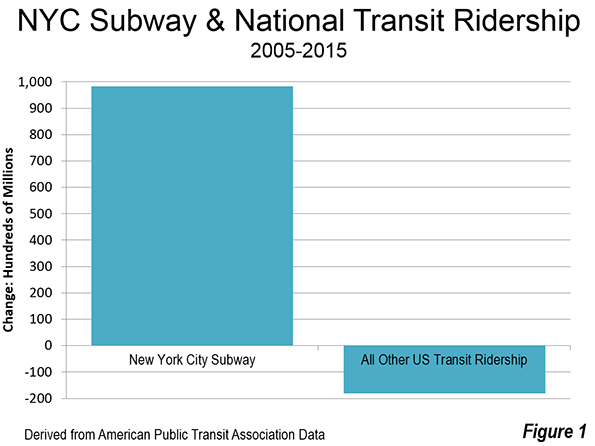

Perhaps the most incredible thing about the New York City Subway has been its utter dominance of the well-publicized national transit ridership increases of the last decade. According to annual data published by the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), ridership on the New York City Subway accounts for all of the transit increase since 2005. Between 2005 and 2015, ridership on the New York City Subway increased nearly 1 billion trips. By contrast, all of the transit services in the United States, including the New York City Subway, increased only 800 million over the same period. On services outside the New York City subway, three was a loss of nearly 200 million riders between 2005 and 2015 (Figure 1).

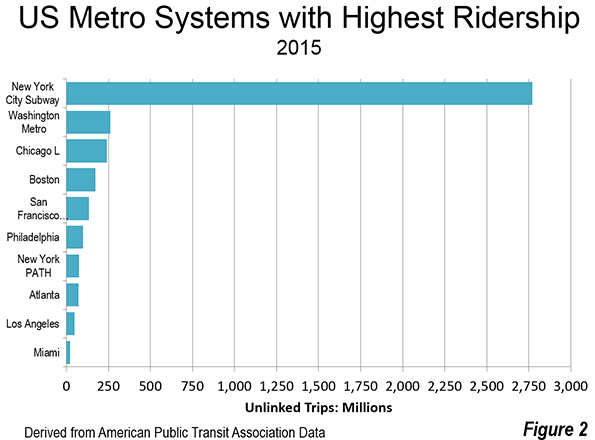

The New York City subway accounts carries nearly 2.5 times the annual ridership of the other nine largest metro systems in the nation combined (Figure 2). This is 10 times that of Washington’s Metro, which is losing ridership despite strong population growth , probably partly due to safety concerns (see America’s Subway: America’s Embarrassment?). Things have gotten so bad in Washington that the federal government has threatened to close the system (See: Feds Forced to Set Priorities for Washington Subway).

The New York City subway carries more than 11 times the ridership of the Chicago “L”, though like in New York, the ridership trend on the “L” has increased impressively in recent years. The New York City subway carries and more than 50 times the Los Angeles subway ridership, where MTA (and SCRTD) bus and rail ridership has declined over the past 30 years despite an aggressive rail program (See: Just How Much has Los Angeles Transit Ridership Fallen?).

With these gains, the New York City Subway's share of national transit ridership has risen from less than one of each five riders (18 percent) in 2005 to more than one in four (26 percent) in 2015. This drove the New York City metropolitan areas share of all national transit ridership from 30 percent in 2005 to over 37 percent in 2015.

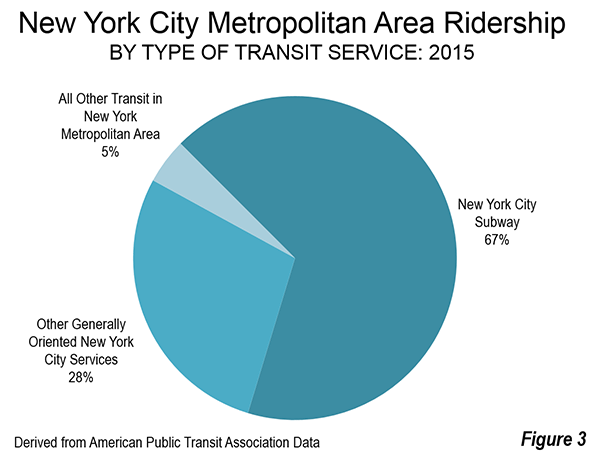

Subway ridership dominates transit in the New York City metropolitan area as well, at 67 percent. Other New York City oriented transit services, including services that operate within the city exclusively and those that principally carry commuters in and out of the city account for 28 percent of the ridership. This includes the commuter rail systems (Long Island Railroad, Metro-North Railroad and New Jersey Transit) and the Metro from New Jersey (PATH) have experienced ridership increases of approximately 15 percent over last decade (Note 2).

Other transit services, those not oriented to New York City, account for five percent of the metropolitan area's transit ridership (Figure 3). By comparison, approximately 58 percent of the population lives outside the city of New York. The small transit ridership share not oriented to New York City illustrates a very strong automobile component in suburban mobility even in the most well-served transit market in the country.

Last year (2014), APTA announced that the nation's transit ridership had reached the highest in modern history, having not been higher since 1957. In fact, the ridership boom that produced the record can be attributed wholly to the New York City Subway. If New York City Subway ridership had remained at its 2005 level, overall transit ridership would have decreased from 9.8 billion in 2005 to 9.6 billion in 2015. The modern record of 10.7 billion rides would never have been approached.

Thus, transit in the United States is not only a "New York Story," but it has also been strongly dependent on the New York Subway in recent years. After decades of decline, the revival of the New York subway is a welcome development.

Note 1: “Metro” is the international generic term for grade separated rapid transit systems. In the United States, the Federal Transit Administration refers to this transit mode as "heavy rail."

Note 2: Separate data is not available in the APTA reports on the for-profit commuter bus operators serving the city of New York from New Jersey.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: New York City Subway diagram by CountZ at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

What makes the New York subway different

So the success of U.S. mass transit in recent years is entirely the success of the New York City subway--perhaps the most atypical rail transit system in the country, and the one most unlike anything today's rail transit cheering squads are boosting. As the lead sentence of the article notes, "The New York subway is unlike any other transit system in the United States."

Always, always, always, when the New York subway system is raised in a discussion of mass transit, the differences have to be kept in the forefront of the discussion.

1) New York subways, for the most part, run 24/7, and run frequently enough to make riding them at least more-or-less feasible. In New York, you can work overtime and still get home without taking a cab, and you can use the subways for your social life in the evening--or all night. That makes a big difference to the yuppies who move to NY, or want to (and those who have money to spend probably do need to work overtime).

2) New York subways were built, by private companies or by the city, in the bad, dark ages when transit systems were built to meet the needs of the people who would ride them. So when the lines were built, the riders came, and they stayed. Today, transit is built to serve the social engineering demanded by naive ideologues, big real estate speculators, the corrupt politicians bought by the speculators, the transit planners bought by the corrupt politicians--and media professionals, almost all of whom are looking to suck their way into jobs in New York or, in the meantime, someplace as much like it as possible.

There are two other false differences that New Age Urbanists may bring up instead:

A) For most New Yorkers, there is no alternative to the subway. Therefore New Age transit plans will succeed just as well, as long as all alternatives are removed or made unworkable. But there IS an alternative to the subway, and very large numbers of New Yorkers eventually take it: move out of the city. Much of the city's population, and especially its tax-paying population, is essentially transient. They will move out in their thirties, to be replaced by new waves of twenty-somethings. (The ones who remain are apt to be won't-grow-ups.) This is not a viable demographic model for other cities. If other cities, when people move out because no sensible adult will stay, those people will not be replaced.

B) As the article notes, New York is much more densely populated than other U.S. cities. This has a lot to do with the viability of mass transit, especially rail transit. New Age Urbanists want all American cities to be this dense. But they never say how this goal will be attained in a democracy. Many of the same people tell us that self-deportation is not a viable scenario for ten million illegal immigrants--unfeasible by virtue of the magnitude, and repugnant to a humane society. But they imply that it's viable and acceptable for the population of the suburbs, to ensure that the cities are dense enough to support rail transit (and that the cities regain the tax base that fled years ago).

By the way, there is an important point to be made about how even New York's subway system is inadequate for the mega-city New York has become. It is particularly inadequate for the young urbanite wannabees who move to the outer boroughs to be in New York. So that part of the city's demographic is likely to remain largely transient. The critical failing is due to the fact that ridership needs have changed from the time when the city's subways were built.

When the subways were built, the ridership wanted transit to and from their jobs, which were mainly in Manhattan, inner Brooklyn and Queens, and a few other industrial areas. People didn't much need to move around from one satellite neighborhood to another, least of all to satellite neighborhoods in other boroughs. Most New Yorkers, often recent immigrants, were settled in more or less homogenous communities, and their family and social ties were to a large extent limited to their ethnic groups and their neighborhoods. If a neighborhood grew and some of the residents hived off, they moved to somewhere down the subway line that was easily accessible from the old neighborhood.

Today, the satellite neighborhoods populated by the new people are dispersed all over the outer boroughs. Subway transit between most of them is not feasible. The lines don't run that way, and riding from one satellite to the center and then out to another satellite can take well over an hour. Cab service is also less feasible trips from one satellite to another.

So the new urbanites who move to the satellite neighborhoods find that their accessible options are limited to their own neighborhoods, unaffordable Manhattan, and other neighborhoods on the same subway line. The mega-city is not available to them. Much of the the neat stuff they've heard about, and many of their friends, are located in some other satellite neighborhood that takes an hour and a half (or more) to get to by subway, and another hour and a half (or more) to get home from. Consider that the round-trip work commute from the newer, remoter, satellites can easily add up to two hours. On work days, then, there isn't much time left to enjoy the mega-city. (And, as always, forget about travelling to do something outside the city.)

New Age Urbanism has solutions for this, of course:

i) Everyone will ride bicycles. But the viability of that alternative falls off drastically with age, kids, and less free time. Also with winter, summer heat, rain, and distance.

ii) People will live in walkable neighborhoods, which, it is implied, will contain everything the residents need to get to frequently: jobs (and enough employers so that they will have a choice), all their friends, and all that neat stuff that's currently located in some other satellite neighborhood or in the center city.

iii) Buses, perhaps, though only as an interim solution, since New Age Urbanism demands rails, not buses. In the interim, however, urban buses tend to stop every couple of blocks. Those stops add up quickly. (Not to mention the time at each stop required for the driver to converse with people who can't read bus schedules and have to ask if this is the bus they want.)

iv) New rail lines. These will either be 1) buried, and thus super-expensive, especially in today's business and regulatory environment, or 2) surface express lines that have to be isolated from other traffic, thus forming the barriers between neighborhoods that New Age Urbanists decry, or 3) local surface trolleys that have the same problems as buses. These lines will run along the wider business streets in each neighborhood. This will have one of two effects: 1) if the buildings on the streets are left intact, the businesses on those streets will be heavily stressed or bankrupted due to decreased traffic and visibility during construction. This will provide many purchase opportunities for real-estate speculators, especially those who kick back to connections in city governments in exchange for advance knowledge and special facilitation of purchases. 2) Whole blocks of buildings will be torn down, to be replaced by new buildings that the old occupants, business or residential, can't afford. This will provide even more opportunities for real-estate speculators--and also for really big developers, the kinds that routinely purchase mayors and city councils.

So the residents of the satellite neighborhoods will be paying mega-city rents (and insurance rates) for the amenities of the much smaller city to which they actually have usable access.