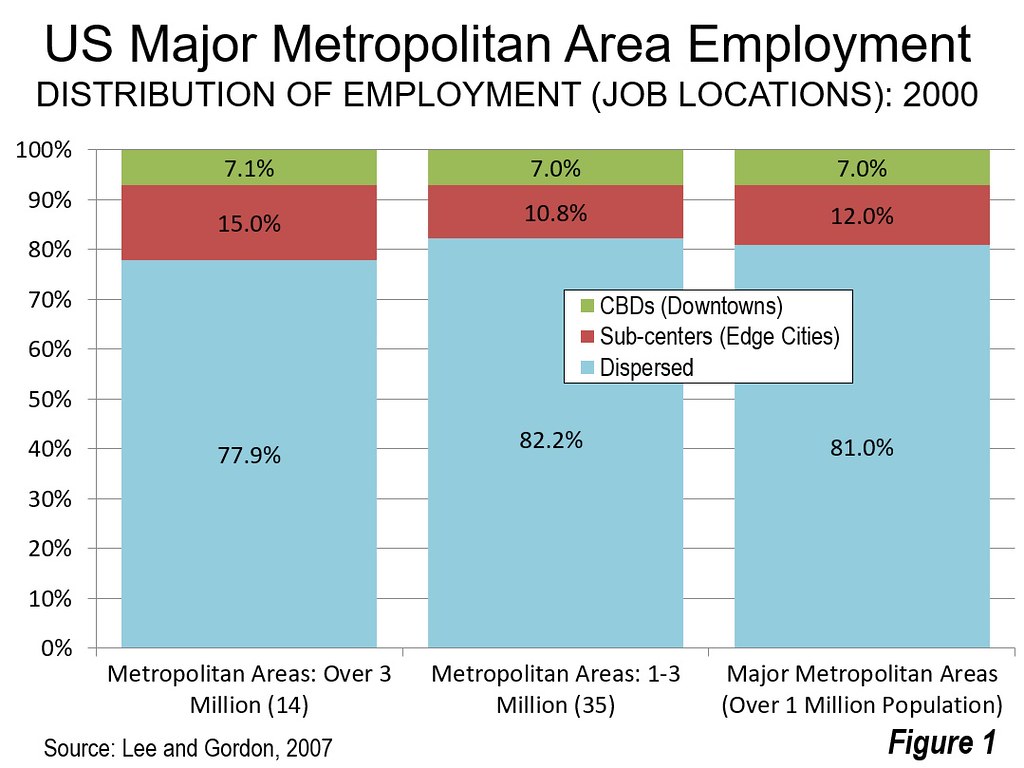

American cities have long been known for their dispersion of employment, moving from mono-centricity, to polycentricity (and edge cities) to, ultimately, dispersion. This transition was documented by Bumsoo Lee of the University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana) and Peter Gordon of the University of Southern California (USC) using 2000 Census data (Figure 1). Even before that, in a 1998 Brookings Institution paper, Gordon and USC colleague Harry W. Richardson observed that employment dispersion to the suburbs helped cities adapt to growth, with “most commuting now takes place suburb-to-suburb on faster, less crowded roads."

Employment Dispersion in Australia

Employment dispersion in Australia’s metropolitan areas is one of the principal messages of a new report by Marion Terrill and Hugh Batrouney of the Grattan Institute (See: Remarkably adaptive Australian cities in a time of growth). The researchers relied upon work place data from the 2016 Census, conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), to estimate the total work day population in the central business districts, sub-centers and all other employment, which is dispersed. Sub-centers are generally synonymous with the “edge city” concept developed by Joel Garreau in his 1999 book Edge City: Life on the New Frontier.

This is despite the fact that Australian cities are well known for their strong central business districts (CBDs or downtowns). Every one of the five major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population) has more CBD jobs than all but 11 CBDs in the United States (out of 53 major metropolitan areas).

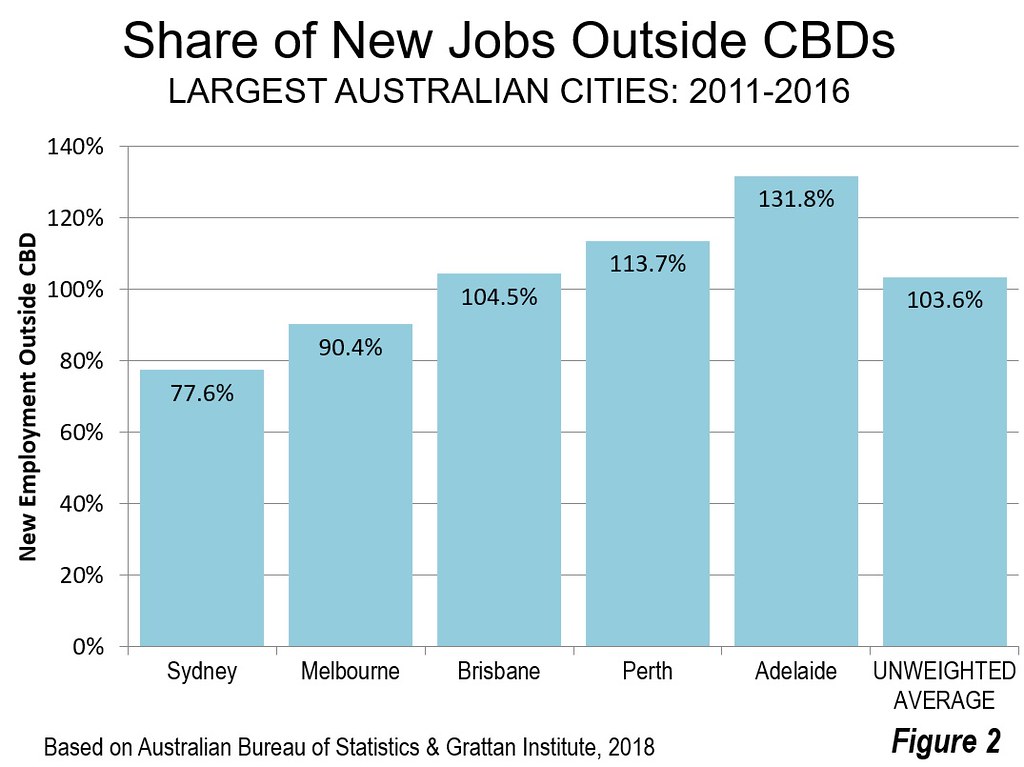

Generally, however, all of the CBDs in Australia’s largest cities are losing market share except in Sydney. Even in Sydney, more than 75 percent of the new jobs have been outside the CBD. In Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide, all of the new jobs have been outside the CBD (Figure 2). In fact, the CBD skyscrapers mask the reality that metropolitan employment is characterized far more by the dispersion of employment than centralization.

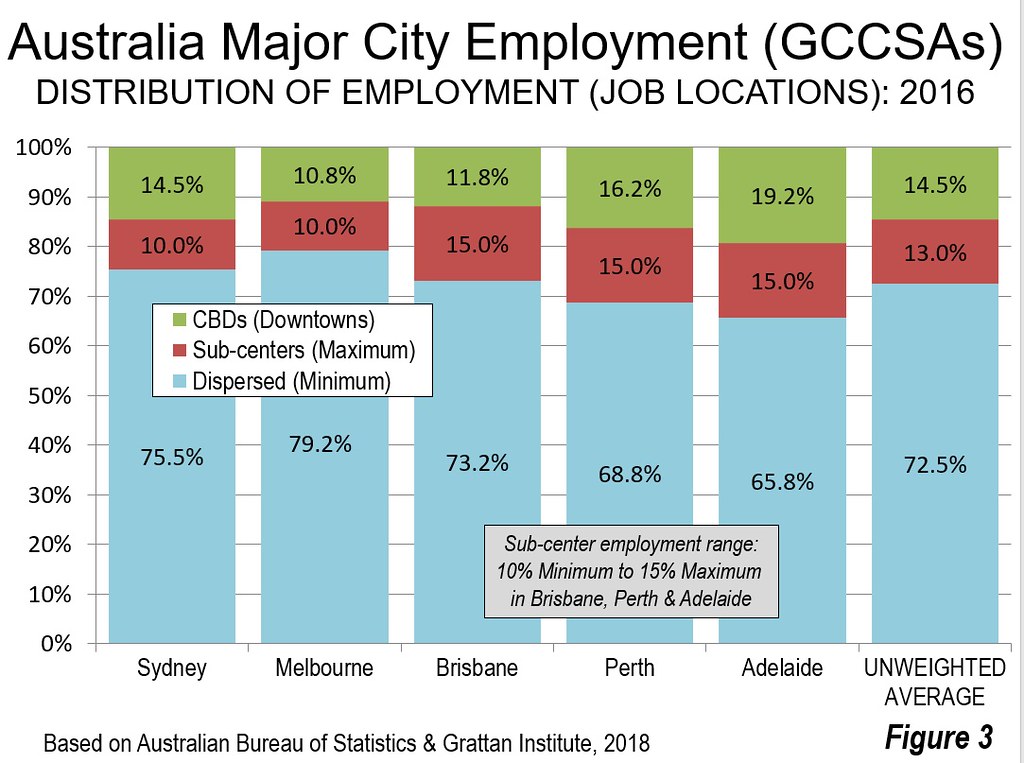

Australia’s five largest cities (Note) are defined by employment dispersion, with a minimum of 74 to 79 percent of employment outside the CBD and sub-centers (Figure 3). This analysis uses the maximum sub-center estimate developed by the Grattan researchers, with the balance being a minimum estimate for dispersed employment.

Sydney: Sydney, capital of New South Wales, Australia’s largest state, has been Australia’s largest city since overtaking Melbourne before the 1911 census. With a 2016 Census count of 4.8 million, Sydney has about the same population as Boston and is halfway between Toronto and Montréal. Sydney has a strong CBD, with 321,000 jobs, between the sizes of the Washington and San Francisco CBDs, which are the third and fourth largest in the US. It is nearly as large as Toronto (Canada’s largest CBD). Yet, the Sydney CBD has under 15 percent of Greater Sydney’s employment.

Terrill and Batrouney estimate Sydney’s sub-center employment at no more than 10 percent of the Greater Capital City Area employment. The remainder, at 77 percent, is dispersed throughout the metropolitan area. This is comparable to that of US metropolitan areas over 3,000,000 population in 2000 (Figure 1, above).

Melbourne: Melbourne is capital of the state of Victoria and Australia’s second largest city, with 4.5 million residents according to the the 2016 census (Melbourne was the largest city from at least 1861 through 1901). This is about the size of Phoenix or Riverside-San Bernardino (though growing faster than both) and somewhat larger than Montréal. According to demographer Malcolm McCrindle, Melbourne could again become Australia’s largest city by 2026. Like Sydney, Melbourne has a large CBD, with 221,000 jobs, nearly as many positions as in the CBDs of Boston, Philadelphia or Montréal. Melbourne added 21,200 jobs in the CBD between 2011 and 2016.

The Grattan Institute report also places sub-center employment at no more than 10 percent of Greater Melbourne. The result is that Melbourne has the most dispersed employment of the Australia’s largest cities, at 79 percent.

Brisbane: Brisbane is the capital of the state of Queensland and is Australia’s third largest city, with 2.3 million residents. This is about the size of Sacramento, Las Vegas or Vancouver. Brisbane’s CBD has 122,500 jobs, about equal to the CBDs of Denver or Ottawa. Approximately 12 percent of Greater Brisbane’s employment is in the CBD. The sub-centers have 10 to 15 percent of metropolitan employment. From 73 to 78 percent of Greater Brisbane’s employment is dispersed.

Perth: Perth is the capital of the state of Western Australia and Australia’s fourth largest city, with 1.9 million residents. This is about the population of Indianapolis or Nashville and between that of Vancouver and Calgary. The Perth CBD has 137,400 employees, about the same size as the Los Angeles CBD and twice that of Edmonton. The CBD has just under 17 percent of the metropolitan area’s employment. The sub-centers have 10 to 15 percent of Greater Perth’s employment. From 69 to 74 percent of employment is dispersed.

Adelaide: Adelaide is the capital of the state of South Australia and the nation’s fifth largest city, at 1.3 million residents. This is about the size of Raleigh, Edmonton or Ottawa. Adelaide’s CBD has 107,600 jobs, This is about equal to the jobs in downtown Minneapolis and slightly less than the Ottawa CBD. Adelaide has the highest CBD employment share in Australia, at 19.2 percent. Its CBD is so large that, it in the United States, Adelaide would rank 12th in employment. By comparison, Adelaide has less than one-half the population of any US metropolitan area with greater CBD employment.

Sub-centers are estimated to have between 10 and 15 percent of employment in Adelaide. The dispersion of jobs outside the CBD and sub-centers accounts for from 66 to 71 percent of Greater Adelaide’s employment.

Sub-center Stagnation Despite Planning Preference

The authors also cite evidence that larger sub-centers, long popular with planners, may add to the dispersion trend. The Greater Sydney Commission indicates that three centers, the CBD, Parramatta and the yet to be constructed Badgery’s Creek (West Sydney) Airport should contain 50 percent of the metropolitan area’s employment by the middle of the century. Today, the CBD and Parramatta combined have less than 17 percent of the employment. Parramatta, site of the 2000 Olympics stadium, has long been considered Sydney’s second downtown and is well served by Sydney’s large urban rail system. Yet Parramatta is not growing in employment share. The authors further note that Melbourne’s less remote Tullamarine Airport has attracted less than one percent of Melbourne’s employment, which may not bode well for Badgery’s Creek.

For policy makers, the implications are clear. As Terrill and Batrouney put it: “Despite governments’ longstanding plans, major suburban employment centres have not in fact been a significant source of jobs. Rather than being located in CBDs or employment sub-centres, the overwhelming majority of workplaces are widely dispersed across metropolitan areas. This characteristic is one reason Australia’s cities are managing to adapt to growing populations.”

Note: The Grattan Institute report also covers Canberra (Australian Capital Territory, the federal capital), Hobart (capital of the state of Tasmania) and Darwin (capital of the Northern Territory), which are not included in this analysis.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Flinders Street Station, Melbourne (by author)