California was once a state of great builders, and its legacy of grand construction projects remains plenty visible today. Major infrastructure investments like the California Aqueduct enabled the sprawling metropolises of the Southern California desert to thrive, becoming some of the most prolific economic and cultural centers in the world. The Golden State pioneered highway construction, linking its cities with each other and the rest of the nation. And perhaps the most iconic symbol of California, the Golden Gate Bridge, was a remarkable civil engineering feat of its time.

But California, and especially Orange County, seems to have stopped building as of late. The state has seen skyrocketing housing costs in its coastal metros, brought on at least in part by a dramatic lack of home construction needed to satisfy demand. The last decade has seen a slowdown of housing construction unprecedented in California’s recent history.

Figure 1: New housing construction has slowed dramatically over the last decade.

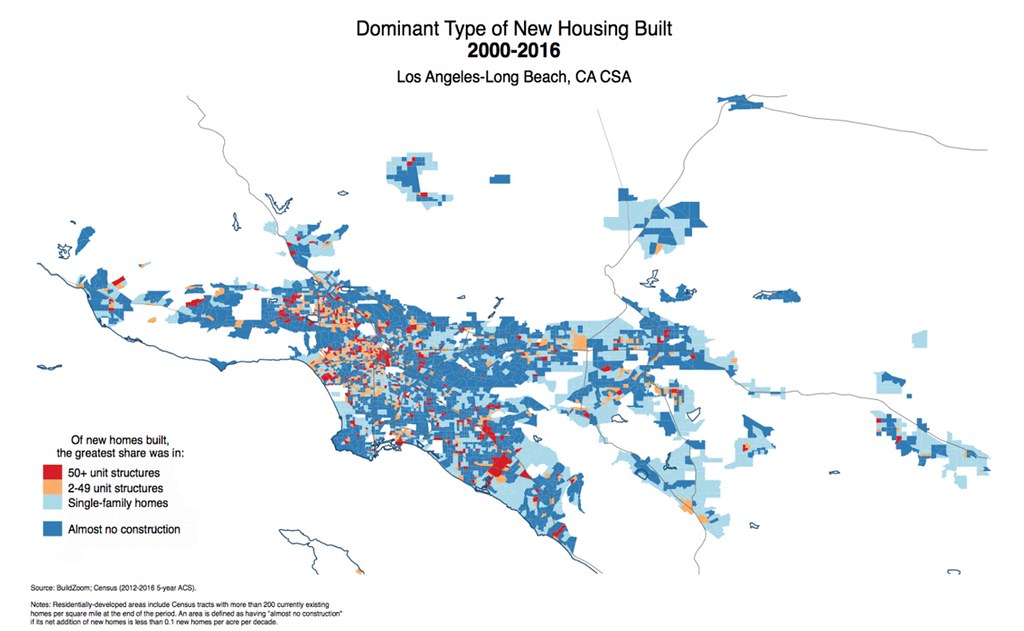

From 1980 to 2000, the Los Angeles-Long Beach Combined Statistical Area, which includes Orange County, saw the addition of a relatively healthy mix of housing stock. But according to Buildzoom data, construction grinded to a near halt between 2000 and 2016 with 52% of all census tracts seeing almost no construction, up from 24% in the twenty years prior. With a few notable exceptions near Irvine and Anaheim’s Platinum Triangle neighborhood, most of Orange County’s housing stock has gone untouched since 2000. The inability of home supply to keep up with demand has, at least in part, contributed to Orange County’s sky-high home prices.

Figure 2: New home construction in Greater Los Angeles has all but stopped, according to Buildzoom.

In addition, mass transit expansion projects aimed at alleviating pressure on rents in California’s glittering beachside cities have also faced waning support. The recently-anointed governor Gavin Newsom rolled back his support for a statewide high-speed rail to link Los Angeles and San Francisco with metros in the struggling San Joaquin Valley in the interior of the state.

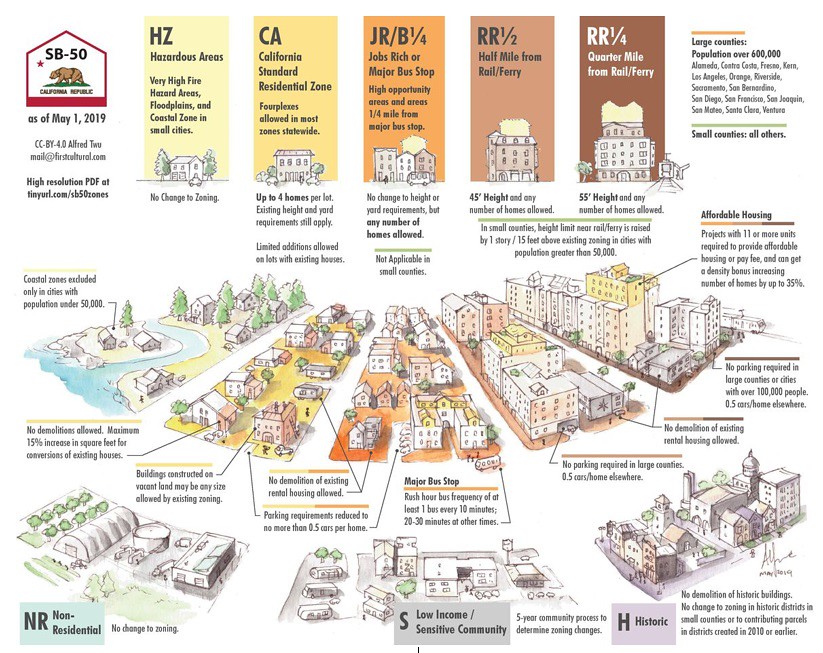

SB50, State Sen. Scott Wiener’s controversial proposal to overhaul single-family zoning near major rail and bus lines in the name of transit-oriented development, was shelved by Sacramento in May and is unlikely to return before 2020. The bill’s first incarnation - SB827 - faced criticism from both wealthy NIMBY activists as well as low-income residents, who feared being priced out of neighborhoods by an influx of new development at the behest of real estate speculators. SB50 included provisions intended to slow the pace of change for locally-defined “sensitive communities” and was backed by a broader coalition that included tenant protection groups, but was unable to overcome opposition in the state legislature.

The theory behind transit-oriented development relies on population density. In sum, more people in less space means more efficient land use and, theoretically, increased demand for public mass transit. While not nearly as dense as San Francisco or Los Angeles, roughly a third of OC’s ZIP codes boast a population density of more than 7000 people per square mile. These sorts of dense neighborhoods are the most likely to see transit-oriented development projects in the near future; below is a map of the overwhelmingly low-income OC neighborhoods that would be subject to zoning changes under SB50, courtesy of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

Figure 3: OC’s “transit-rich” neighborhoods are concentrated north of the 55 freeway.

A look at two years’ worth of public opinion data collected by Chapman University provides an overview of attitudes towards the development of housing and public transportation that can be measured against population density across Orange County’s neighborhoods. The study asks a simple question: are residents in OC’s densest neighborhoods more receptive to the kind of transit-oriented development projects being pushed by Sacramento?

To answer this question, this study draws upon six questions from the 2018 and 2019 editions of the Orange County Annual Survey out of Chapman University. Responses were examined at the ZIP code level in order to test for differences of opinion among neighborhoods.

Figure 4: NIMYIMBY

Figure 5: STRATEG4

Figure 6: OCRAIL

Figure 7: PUBTR1

Figure 8: LIVEPFE

Figure 9: CO2

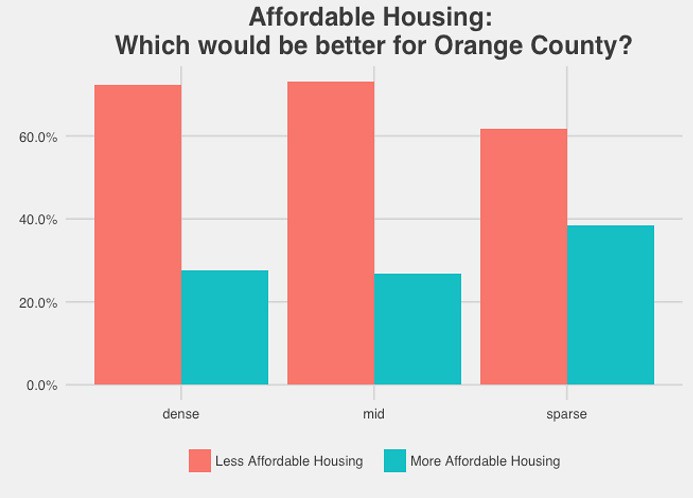

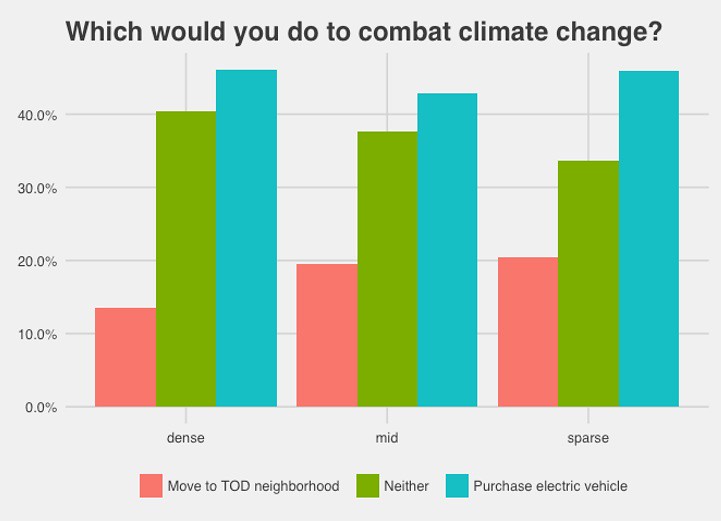

Results by density proved to be very much in line with the overall population of Orange County – opinion on questions relating to the development of housing and transit is nearly identical across density labels. Very little difference exists between the Dense ZIP codes and the more sparsely populated ZIP codes, with only a few percentage points of difference between groups.

With opposition to development evenly distributed across densities, it appears as though there are few areas within Orange County where the majority of residents support the large-scale development of housing and public transit infrastructure. Public opposition to transit-oriented development, especially in OC’s densest neighborhoods, suggests serious feasibility issues. It is worth noting that SB50’s changes would have applied only to counties with more than 600,000 residents, exempting many of the state’s comparably suburban counties like Marin and Napa in the north Bay Area.

It is interesting also to note the disconnect between living preferences and policy preferences among Orange County residents. Although residents considered “Housing Affordability” to be the number one issue facing Orange County in both surveys, some 70% of residents opposed the construction of more affordable housing in Orange County. Although a plurality (49%) of Orange County residents would prefer to live in a “smaller home in a more urbanized area” only around 17% of residents would rather relocate to a transit-oriented community than invest in an electric vehicle.

Figure 10: An overview of SB50, which was shelved in May, from Curbed SF.

While this study suggests that support for transit and housing expansion is no higher in dense areas than in other areas of Orange County, these findings also suggest that higher density in a particular area is not associated with an increase in relative opposition to development. This could be explained by the fact that more densely populated neighborhoods tend to see more frequent and rapid development than more sparsely populated neighborhoods due to their sheer size, and as such are more accustomed to neighborhood change.

Additionally, although the majority of Orange County residents oppose affordable housing and transit projects, the margins are closer than one might expect in a county where 87% of the population uses their car every day. OC residents are nearly evenly split across densities on the concept of light rail, suggesting that future transit projects are still within the realm of possibility from an electoral standpoint, especially as Orange County’s politics continue to shift. An average of 41% of residents across densities would rather improve mass transit than expand highways. Feasibility, on the other hand, is another issue: If the 17% of residents that would move to a TOD community actually did so, that accounts for approximately half a million people, enough to create several sustainable transit-oriented neighborhoods – but it seems unlikely that residents would readily give up their personal vehicles at such a scale in practice.

The debate surrounding transit-oriented development in Orange County likely won’t be over any time soon. SB50 may be shelved for now, but it will undoubtedly rear its head again in 2020. Radical reform will be necessary to fix California’s housing crisis, and Sen. Wiener should at least be lauded for moving the conversation towards an actionable solution. But any solutions handed down from Sacramento will have to account for differences in public opinion and attitude towards public transit across California’s diverse urban geography to ensure that policy outcomes can match Sacramento’s rhetoric.

The full study is available here.

Alex Thomas works as a research analyst for a real estate consulting firm in Irvine, CA. Previously, he has served on research teams at the Brookings Institution in the Metropolitan Policy Program, the Center for Opportunity Urbanism, and the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University. He holds a B.A. in Political Science from Chapman University, and originally hails from the Silicon Valley.

Top photo: OC’s most recent transit expansion, the OC Streetcar, is projected to open in 2021.