Even before 2020, America’s great cities faced a tide that threatened to overwhelm them. In 2020, the tsunami rose suddenly, inundating the cities in ways that will prove both troubling and transformative, but which could mark the return toward a more humane, and sustainable, urbanity. The two shocks—the Covid-19 pandemic in the spring, followed by a summer punctuated by massive social unrest—have undermined persistent fantasies of an inevitable “back to the city” migration.

Before the pandemic, cities were already experiencing a huge class divide, slackening population growth, rising crime, and dysfunctional schools. Their white-collar-dominated economies were clearly vulnerable to technological changes, and they were presided over by a political class increasingly out of touch with reality and often hostile to middle-class concerns. Now, the urban white-collar employment and tourism economies have been devastated, while other sectors such as manufacturing, port development, and logistics had already departed.

The weeks, even months, of civil disorders occurring after the death of George Floyd may prove even more consequential. Cities were already facing rising crime before the Floyd incident. Last year, New York’s bodegas experienced a 222 percent increase in burglaries, while brick-and-mortar chains like Walgreens were shutting down locations in San Francisco due to “rampant burglaries.”

More middle-class families appear happy to have relocated to the suburbs, or to places even farther away, where houses are less expensive. One in five Americans, according to Pew, knows someone who has moved due to Covid.

The Pandemic Impact

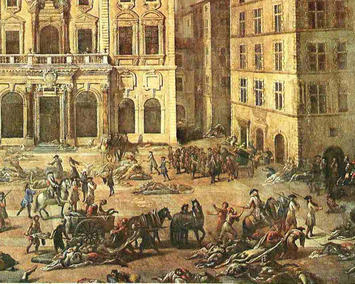

The pandemic exposed what has long been an urban weakness. Since ancient Greece, crowded conditions, combined with intense poverty and connections to distant marketplaces—often the seedbeds of novel diseases—have made cities naturally more susceptible to pandemics than the countryside.

In his brilliant history of Rome, Kyle Harper describes how the thriving but very dense cities of the precociously urbanized Empire became “victims of the urban graveyard effect.” Attracting migrants from across the empire, fetid cities served as “petri dishes” for parasites and viral infection. Similarly, the Black Death in the Middle Ages spread throughout Europe, but it was poor urban dwellers who suffered most, notes historian Barbara Tuchman. Cities eventually recovered, but remained constrained and many communities actually disappeared.

The association of urban density, poverty, and disease persisted through the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution—its pandemics were well chronicled by Engels—to the Spanish flu a century ago. This association has continued to hold in the case of Covid-19, despite the pandemic’s relentless spread. Indeed, even after the surge of cases in more rural areas, fatality rates in counties with the highest urban densities—particularly those which have greater overcrowding in housing, the greatest mass transit dependency, and deepest pockets of poverty—have seen the most fatalities. In the United States, at the end of 2020, counties with urban densities greater than ten thousand people per square mile constitute 3 percent of the nation’s population but have suffered 8.8 percent of deaths associated with the pandemic, 2.5 times their proportional share. By comparison, in typical suburban areas (urban densities of one thousand to five thousand per square mile), where 81 percent of the population lives, the COVID fatality rate is 60 percent lower.

This reflects what can be best described as the impact of “exposure density” brought on by crowded housing, transit, elevators, and office environments. These challenges will likely not end even with a vaccine or herd immunity. As Laurie Garrett pointed out three decades ago in The Coming Plague, the growth of crowded megacities or what she calls “urban Thirdworldization”—such as we see in China’s dense and unsanitary cities—seems ideal for creating new pandemics, like SARS, MERS, and swine flu. The National Institutes of Health’s Anthony Fauci sees potential new viruses already incubating in China and warns that more pandemics may arise in the near future.

Read the rest of this piece at American Affairs Journal.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute — formerly the Center for Opportunity Urbanism. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin

Some middle ground...

...will likely be found to accommodate the essential efficiencies of urban living while providing separation. This Twitter stream examines a housing trend, in Houston particularly where zoning strictures are relaxed. Note the New Urbanists do not approve because the personal vehicle is maintained as a transit option: https://twitter.com/ebwhamilton/status/1363666879873744896